Credits

Feature by: Rumsey Taylor, Cullen Gallagher, Katherine Follett, Victoria Large, Leo Goldsmith, Steve Macfarlane, Veronika Ferdman, and Jared Eisenstat

Posted on: 01 April 2013

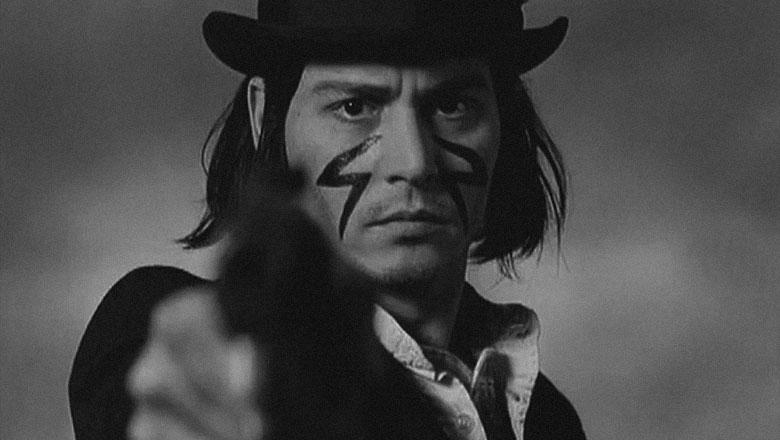

You know, I’ve had it up to here with this Indian malarky. I haven’t understood a single word you’ve said since I’ve met you—not one single word.

—William Blake, Dead Man

The term “acid Western” was first used by Pauline Kael in her 1971 review of El Topo.1 The film had just received its formal premiere after having played for some six months straight at a shabby theater in downtown New York named the Elgin, at which it received essentially no advertising and played exclusively at midnight. Nevertheless, the film did peculiarly strong business and became a curious fixation. El Topo was pulled from the Elgin and armed with a national distributor who aimed to replicate its success in other U.S. cities. Its belated premiere, at a theater in Times Square in November of 1971, is when Kael and other critics from the mainstream press would see the film for the first time, and it is here where they found themselves amid the film’s most integral component: its audience, perceptibly under the influence of some mind-altering substance.

For Kael the acid Western was a derogatory allusion to the pothead audience that extolled the film—an audience she admittedly did not belong to. In her review she expends many words in describing those in attendance with her, whom she observes unjudgementally but alertly, as one would animals at a zoo. J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum elaborate on the phenomenon in their 1980 book Midnight Movies, in which an entire chapter is devoted to El Topo:

Although hip film buffs objected to El Topo’s graceless amalgam of Luis Buñuel, Federico Fellini, Sergio Leone, Sam Peckinpah, and Jean-Luc Godard, the movie bypassed cinematic sophistication to address the counterculture directly.2

Rosenbaum reprised the term in his review of Jim Jarmusch’s 1995 film, Dead Man, and in conjunction with Kael’s writing delineated the rough parameters of the makeshift subgenre. For Rosenbaum the acid Western refers to Jarmusch’s film foremost, and retroactively to a slew of films from the late 60s and early 70s that share Jarmusch’s inversion of the Western formula. These films generally posit an individualist journey that ends not in triumph but often in suffering and death—a narrative trajectory Dead Man summates in its very title. Rosenbaum elaborated thusly:

What I partly mean by ‘acid Westerns’ are revisionist Westerns in which American history is reinterpreted to make room for peyote visions and related hallucinogenic experiences, LSD trips in particular. […] Both ‘acid Westerns’ and ‘pot Westerns’ depend on reevaluations of white and nonwhite experience that view certain countercultural habits and styles in relation to models derived from Westerns, but where they differ most, perhaps, is in their generational biases, which lead them respectively to overturn or ironically revise the relevant generic norms.3

At the time of their conception, acid Westerns extended the already-incipient trend of Western revisionism that was underway in Hollywood, sometimes by the genre’s most popular and radical practitioners. The most abrasive of these would be Sam Peckinpah, whose 1969 The Wild Bunch itself appealed to the counterculture’s more politicized faction for its potency as an analogy of violence in Vietnam. “The Western is a universal frame,” Peckinpah remarked, “within which it’s possible to comment on today.” Traditionally, the Western was an index of America’s exceptionalism, a document of the U.S.’s imperialistic growth. Acid Westerns are a response to this tactic, in that they’re generally more concerned with the suppression and hostility enacted to facilitate that growth. The first and purist examples were made in the late 60s, in which the counter-culture asserted a brief yet emphatic hold on the Hollywood machine. This audience engendered the success of films in which heroes were decidedly anti-authoritative (The Graduate) and their plights strewn in prejudiced opposition (Easy Rider). But unlike its mainstream counterparts, the acid Western caters more specifically to a bohemian audience befitted by the influence of a hallucinogenic substance of some sort, the same audience that would give birth to the ritual of the midnight movie in the 70s. It is in this regard that the acid Western is exemplified in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo. Kael describes the film’s phenomenon as such:

Jodorowsky has come up with something new: exploitation filmmaking joined to sentimentality—the sentimentality of the counter-culture. They mix frighteningly well: for the counter-culture violence is romantic and shock is beautiful, because extremes of feeling and lack of control are what one takes drugs for. What has has been happening, I think, is that the counter-culture has begun to look for the equivalent of a drug trip in its theatrical experiences. I think it still responds to non-head movies if there’s a possibility of direct identification with the characters, but increasingly movies appear to be valued only for their intensity.4

This “intensity” is a response to the violence in Jodorowsky’s film, but in a general sense it describes the tone of a true acid Western: a film that amalgamates the violent with the absurd in such a way that the result, to a specific audience, achieves a certain profundity.

For the next three weeks, we aim to indicate the extent and peculiarity of the acid Western subgenre. Please refer to this page for updates throughout the month.

Introduction by Rumsey Taylor.

- “The avant-garde devices that once fascinated a small bohemian group because they seemed a direct pipeline to the occult and ‘the marvelous’ now reach the new mass bohemianism of youth. But the marvelous has become a bag of old Surrealist tricks: the acid-Western style is synthesized from devices of the once avant-garde” ↩

- J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum, Midnight Movies (Da Capo Press, 1983) 98. ↩

- Jonathan Rosenbaum, Dead Man (British Film Institute, 2000) 51. ↩

- Pauline Kael, rev. of El Topo, dir. Alejandro Jodorowsky, The New Yorker (20 Nov. 1971) ↩

By Rumsey Taylor, Cullen Gallagher, Katherine Follett, Victoria Large, Leo Goldsmith, Steve Macfarlane, Veronika Ferdman, and Jared Eisenstat ©2013 NotComing.com

Reviews

-

Ride in the Whirlwind

1965 -

The Shooting

1966 -

El Topo

1970 -

The Hired Hand

1971 -

The Last Movie

1971 -

Greaser’s Palace

1972 -

Bad Company

1972 -

Ulzana’s Raid

1972 -

Jeremiah Johnson

1972 -

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid

1973 -

Kid Blue

1973 -

Dead Man

1995

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.