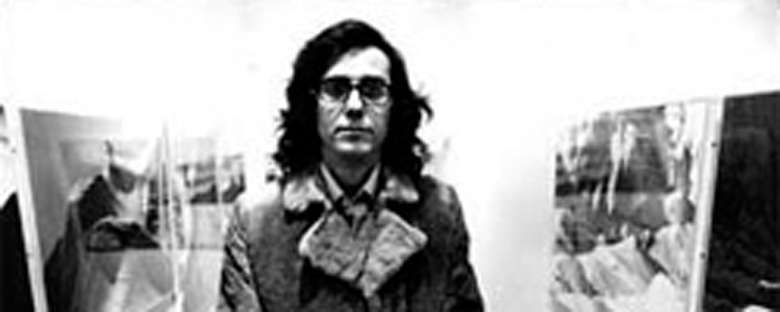

The persistent image of Christo is of a man, personalized in thick-rimmed glasses and with disheveled hair, declaring the purpose of his art in a county courtroom hearing. This occurs in varying instances and locations throughout his career as an installation artist, whose aesthetic signature is adorning an environment (usually a man-made structure) with fabric. In the majority of these instances, Christo fails to gain permission, and even in the ones that succeed (five of which are detailed in the Maysles brothers’ films included in this box set) the public is suspicious as to what, exactly, is the purpose of these giant installations.

Given the austerity of Christo’s projects, as well as the underlying conflict of combining edifice and nature, such suspicion is inevitable. Christo speaks with enthusiasm but without clarity. Because his are each large-scale, independently funded projects (he and wife Jeanne-Claude accept no donations for their work), he must enlist permission from local and national governments. Christo meets and proposes his ideas to the landowners across the world in an effort to permit his work on their property: be it farmers in coastal Japan or Miami politicians (who represent desolate municipal property), and, in response, each must confront and articulate their perception of art and what collective benefit it may hold. This “confrontation” occurs even with knowledge of the concept of Christo’s work.

The films included in this set are fascinating as a collective documenting. The first feature, Christo’s Valley Curtain, is the oldest, and finds the both the Maysles and Christo and Jeanne-Claude in their youth. Umbrellas finds the same people nearly twenty years later, driven by identical convictions and hindered by identical endurances. These films are secondarily fascinating for their extensive inclusion, documenting both a history of Christo’s works and the Maysles’ interest in following him around the globe. Appropriately, the final film is an ambitious, extensive project for both creative parties.

Each film contains commentaries by Albert Maysles, Christo, and Jeanne-Claude, and the set includes a 2003 video interview. They appear starkly older than in Christo’s Valley Curtain, and sit in front of preliminary sketches of a forthcoming project (entitled Gates, to be built in New York’s Central Park).

There is a failure to appraise Christo’s work immediately, but it is best experienced rather than conceptualized. Even he and Jeanne-Claude describe their work in simplified, even childish terms, analogizing their work’s brief interval to the “Once Upon a Time” mystique of a fairy tale. The films included in this set each contain a “token conceptualization” that precedes each project. People fail to articulate the benefit of this public art, and even supporters fail to agree with what Christo is insufficiently saying — suggestively, the struggle of explanation hinders Christo more than gaining permission from local governments. Criticisms and rationality aside, each film culminates in footage of a completed project, and in every case it’s austere and quietly beautiful.

Christo’s Valley Curtain

The curtain is a gigantic, fluorescent orange fabric strewn between a pair of accessible mountains. It is anchored via extensive cabling, and requires the efforts of an entire construction crew to be built. This film details the final two days of the curtain’s assembly.

Running Fence

The construction of the fence requires several laborers, and Christo running between them all, dressed in thick glasses, mulleted, and in a hard-hat. This is the endearing image of the Bulgarian-born Christo, as a frantic artist commanding his crew with an accent that seems to intensify with volume.

Islands

Christo selects and speaks of his materials carefully; in many cases, his works are to be experienced and felt. His Islands, however, are too remote for easy inspection. Regardless, as a sight alone, Islands is undoubtedly the most surreal of Christo’s works.

Christo in Paris

This film documents twenty years of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s lives as artists, corresponding roughly with the tenure of preparation to wrap the Pont Neuf in Paris.

Umbrellas

Umbrellas documents what is perhaps Christo’s most extensive project, to plant hundreds of giant umbrellas on the Pacific coasts of California and Japan. There is an obvious ethnological relevance to this — the umbrellas are either yellow or blue, to correspond with the dry and wet environments — yet the work results in unexpected repercussions that convey more about each culture than intended.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.