Reviews

Brian Clemens

UK, 1974

Credits

Review by Budd Wilkins

Posted on 03 June 2013

Source Paramount DVD

Categories Failed Franchises

By the early 1970s, Hammer Film Productions’ flagship Dracula and Frankenstein franchises were suffering from a severe case of enervation—a certain bloodlessness, if you will. These series had settled into well-worn ruts out of which not even an ill-conceived updating (Dracula A.D. 1972) and a change-up in lead actors (Peter Cushing out, Ralph Bates in for The Horror of Frankenstein) could extricate them. Executives, foremost among them studio head Michael Carreras, responded to dwindling audience numbers, as well as emerging trends and new approaches to genre material signaled in films like Night of the Living Dead and Rosemary’s Baby, by upping the ante on both carnality and carnage. A perfect example of this would be the so-called Karnstein Trilogy (comprised of The Vampire Lovers, Lust for a Vampire, and Twins of Evil), a series that ramps up the titillation factor in their progressively more freeform adaptations of the Sheridan Le Fanu source material with an increasingly lurid emphasis on incest and lesbianism. Another tack taken by Hammer was to open up production facilities to non-studio talent with an eye to providing an infusion of fresh blood. Accordingly, studio executives approached Brian Clemens and production partner Albert Fennell, who had created several successful British TV programs like Danger Man (known in the US as Secret Agent) and The Avengers. Given more or less free rein on the project, Clemens co-produced, wrote and directed Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter. Clemens’ express intention was to stand the prevailing clichés of the vampire film on their head. For one thing, the bloodsuckers in Captain Kronos don’t actually drink blood; they bestow a “vampire’s kiss” on their victims, thereby draining them of their youth and vitality.

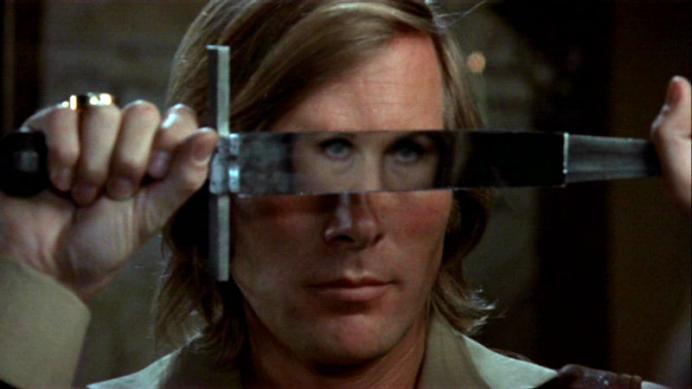

In stark contrast to the stuffed-shirt authoritarians who often figured as protagonists in Hammer films (think Peter Cushing as stern, moralistic Professor Van Helsing), Captain Kronos holds up a hero more in tune with young audiences. Kronos is portrayed as a pot-toking, samurai sword-wielding, antiestablishment type. Kronos’ first action in the film, appropriately enough, is to liberate young gypsy girl Carla, played by Hammer ingénue Caroline Munro (fresh from the aforementioned Dracula A.D. 1972), who’s been clapped in the stocks and pelted with rotten vegetables for “dancing on a Sunday.” Kronos’ outsider status was given added emphasis by casting German actor Horst Janson in the role. Although Janson’s Teutonic tones were dubbed in post by a native Brit, Kronos still betrays faint traces of a Continental accent. Clemens invests Kronos with a lightly sketched out backstory that reveals the motivations for his crusade: His mother and sister were turned into vampires and tried to convert him into one as well. (Somehow he managed to survive the bite.) Such a combination of emotional loss and psychological compulsion aligns Kronos with a myriad of tormented protagonists that span practically every genre; interestingly, one contemporaneous example was Marvel Comic’s own resident vampire hunter, Blade, who was introduced in the pages of The Tomb of Dracula in the same year that Clemens’ film was made. In addition, the figure of the Captain can be seen to anticipate Joss Whedon’s revisionist horror series Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Clemens freely incorporates the iconography of other genres in order to further undermine horror tropes. Like many a film and TV western hero, Kronos travels the countryside along with his sidekick. “Professor Hieronymous Grost,” he introduces himself to Carla, doffing his hat. “Professor?” she echoes. “At least, I profess to be,” Grost shoots back. Clemens contributes many such flourishes of wit and wordplay, an element that’s conspicuously lacking in much of Hammer’s deadly serious outings. Other lines like “What he doesn’t know about vampirism wouldn’t fill a flea’s codpiece” and the matter-of-fact declaration “Toad in the hole” hint at a camp sensibility at work, an attitude toward the material that doesn’t necessarily seek to undercut it - as in, say, Roman Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers - so much as to supply some contrapuntal comic relief. In addition to the figure of the sidekick, Captain Kronos features the Western’s trademark quick-draw contest, reconfigured to allow for some spirited swordplay instead of a shootout, thus necessitating the inclusion of an entire subplot that establishes the villainous Kerro as a proper foil for Kronos. Kerro may be a brawling bastard, but when he starts picking on poor hunchbacked Grost, that’s where Kronos - like Billy Jack with a broadsword - draws a line in the sand.

Among the varied techniques that Clemens uses to toy with audience expectations, one of the most effective is his tweaking of gender stereotypes in the depiction of Paul and Sara Durward, scions of the local aristocracy. As played by Shane Briant, Paul exudes an air of menace, a kind of sneering superciliousness; at the same time, Briant evinces a touch of fey effeminacy in his mannerisms. Conversely, Sara is a trifle butch in her preference for dressing like an English squire, rather than sporting the kind of flowing, frilly gowns the other young women in the film wear. What’s more, there are subtle insinuations of an incestuous relationship between them, as in the scene where Paul hand-feeds Sara grapes, all the while expounding upon the Durward family’s penchant for protracted youth. With their overweening narcissism and unmitigated horror of aging, Paul and Sara seem like an acute parody of the counterculture and its dictum “Never trust anybody over thirty.” Things, however, are not quite so clear cut; for, as much as these finely brushed strokes of character delineation work to signify culpability in the murders, the final twist reveals these potential perpetrators as little more than passive victims of their depraved elders.

Because Clemens clearly intended Captain Kronos as the first installment of an ongoing series, on down to having Kronos and Grost ride off into the (rather fog-shrouded) sunset at the end, he takes great pleasure in “revamping” the vampire mythology. The dialogue makes much ado about the manifold variety of species that exist, how each kind kills in its own particular fashion as well as requiring its own unique method of dispatch. When delays in the film’s release (it was shot in 1972 but didn’t come out until two years later) and dismal box office returns indicated with equal clarity that such a franchise was not in store for the Captain, Clemens attempted to reconfigure the material into a TV pilot, wherein Kronos (playing on the original Greek meaning of his name) would move freely about both space and time in his quest to eradicate vampires of every species. Presumably the show would have played like some off-kilter hybrid of Doctor Who and Kolchak: The Night Stalker.

More Failed Franchises

-

Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter

1974 -

Doc Savage: Man of Bronze

1975 -

Zorro

1975 -

Flash Gordon

1980 -

The Legend of the Lone Ranger

1981 -

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension!

1984 -

Supergirl

1984 -

Dune

1984 -

Masters of the Universe

1987 -

Howard the Duck

1986 -

Willow

1988 -

Dick Tracy

1990 -

The Rocketeer

1991 -

V.I. Warshawski

1991 -

The Shadow

1994 -

Godzilla

1998 -

The Zero Effect

1998 -

The Mod Squad

1999 -

Hulk

2003 -

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

2003 -

John Carter

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.