Reviews

Tim Burton

USA, 1994

Credits

Review by Victoria Large

Posted on 19 May 2014

Source Touchstone Home Entertainment DVD

Related articles

Features

The End

As a director, Tim Burton has always been especially interested in outsiders and outcasts: people who exist in their own little worlds or on the fringes of ours. And while it’s easy to snark about a man who regularly helms mainstream blockbusters claiming any kind of outsider status (“I’ve noticed that after a director makes his first $50 million, he usually makes a movie about how tough it is to be a sensitive soul,” Paul Rudnick cracked in a review of Edward Scissorhands over twenty years ago), Burton’s identification with misfits nevertheless remains a welcome departure from Hollywood’s indefatigable obsession with all that is standardized, predictable, and pretty.

It of course makes sense that Burton’s best film to date is about Ed Wood, one of the most famed outsider artists of the twentieth century. Wood’s low budget films are cherished by cultists for their stilted dialogue, poor production values, and blatant lapses in continuity, but his pictures are also unexpectedly personal in a way that other B-movies of Wood’s era rarely are, particularly in the case of Wood’s first feature, Glen or Glenda, which draws on its writer-director’s own experiences as a transvestite. Ed Wood’s fans regard the man with a curious combination of derision and appreciation: as much as we chuckle over his hubcap flying saucers and wobbly sets, we can’t help but love him for trying, and for being so unabashedly himself. So while Burton’s Ed Wood is a comedy, it succeeds largely because it shares the affection that the fans have for Wood. It likes him more than it laughs at him.

Based on Rudolph Grey’s book Nightmare of Ecstasy: The Life and Art of Edward D. Wood, Jr., the screenplay by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski wisely keeps its focus narrow, concentrating on Wood’s activities in the 1950s, when production of Glen or Glenda? and the director’s best known sci-fi/horror pictures, Bride of the Monster and Plan 9 from Outer Space, took place. Wood had something of a repertory of misfits in his personal orbit as well as in his films: a down-on-his luck Bela Lugosi, blacklisted horror host Vampira, wrestler Tor Johnson, charlatan psychic Criswell, and drag queen Bunny Breckinridge, among others. Alexander and Karaszewski recognize this built-in cast of characters as a gift, and emphasize the camaraderie between Wood and his unusual assortment of actors. And while the screenwriters do take dramatic license, streamlining some parts of Wood’s story as well as privileging, adding, or subtracting details in the service of their tone and themes, a surprising number of scenes come straight from the accounts in Grey’s nonfiction book. (Anecdotes borrowed from the book include the kidnapping of a fake octopus from a props warehouse, Lugosi launching into his dramatic Bride of the Monster monologue on a street corner, and Vampira riding public transit in full bloodsucker regalia.)

The film is spry and funny in its exploration of Hollywood’s outer limits, and much of its heart lies in how it embraces those who are marginalized. That preoccupation provides Ed Wood with some of its most resonant moments, including one in which Wood’s future wife Kathy reacts calmly and kindly to Wood’s confession that he likes to wear women’s clothes. Later, Kathy notes that Wood is “the only fella in town who doesn’t pass judgment on people,” and Wood chirps, “That’s right. If I did, I wouldn’t have any friends.” In one particularly memorable scene, Wood does a veiled striptease at the wrap party for Bride of the Monster, decked in an angora sweater, a long blonde wig, and a tasseled brassiere. At the climactic moment in the dance, he tears away his veil to cheerfully reveal the row of teeth that he lost in World War II. It’s a thing of strange beauty: a celebration of square-peg-ness, self-acceptance, and self-expression that nearly feels like the movie in miniature.

Johnny Depp is marvelous in the title role, conveying the character’s tireless optimism without turning him into a one-dimensional cartoon. The Wood of this film is passionate and endearingly sincere, so much so that we still like him even at his most baldly opportunistic—for instance, when he gives his girlfriend Dolores’ long-promised leading role to an aspiring actress willing to invest in Bride of the Monster, or talks a Baptist congregation into funding Plan 9 from Outer Space. Wood made exploitation pictures, and so it’s appropriate that we see him hunting for resources to exploit, including the famous name of Bela Lugosi, who “starred” in three of Wood’s pictures—including an infamous posthumous appearance in Plan 9, where Wood employed an easy-to-spot “double” in order to complete Lugosi’s part.

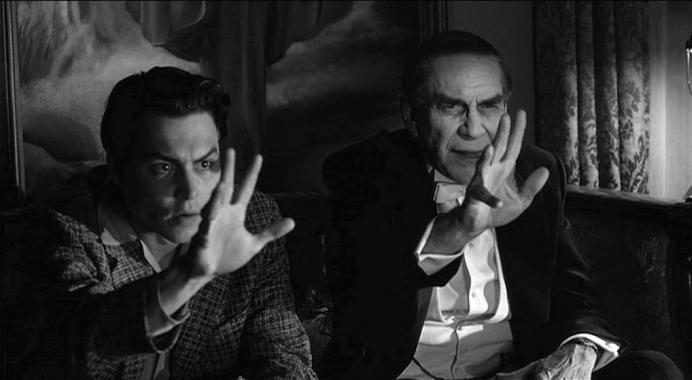

Burton and the screenwriters take pains to portray Wood’s relationship with Lugosi as a benign one, emphasizing the pair’s friendship and the support that Wood offered Lugosi as he struggled with drug addiction and financial problems. Depp and Martin Landau, who won an Academy Award for his turn as Lugosi, have great chemistry as the unlikely duo—especially in a scene where the two bond over a TV broadcast of White Zombie. And while it’s easy to understand, and sympathize with, criticisms of the film’s characterization of Lugosi as a foul-mouthed man still nursing a grudge against fellow horror icon Boris Karloff (according to interviews with Lugosi’s son, neither detail is correct), Landau’s performance is powerful, and the film’s stance toward the horror legend is ultimately a compassionate one.

Indeed, this is a strikingly humane film (perhaps made more striking by the fact that Burton would go on to gleefully immolate an all star cast in his next effort, Mars Attacks!). Though I’ve enjoyed and frequently revisited the macabre fantasias conjured by Burton in the likes of Sleepy Hollow and Sweeney Todd, I admire the gentleness and restraint of Ed Wood, which is stylishly shot in 1950s-homaging black and white but relatively rooted in reality. It knows that Hollywood needs little help in appearing surpassingly bizarre. Like Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, which he directed at the start of his career, Ed Wood shows us that Burton can bring a strong comedic script to the screen with panache.

The film closes on a sweet note—Wood driving off with Kathy after triumphantly introducing Plan 9 from Outer Space at its premiere. An epilogue before the closing credits informs us of Wood’s “slow descent into alcoholism and monster nudie films,” but we see nothing of it. That approach makes sense for this take on Wood’s story, which is more interested in the director’s individuality, creativity, and can-do spirit than the eventual decline of his career and health. Ed Wood’s story is - rather unexpectedly, and with surprising effectiveness — offered to us as an inspiration, the tale of an artist working hard to realize his unique and inimitable visions. That Wood’s films are odd and flawed ends up feeling quite secondary to the fact that they exist at all, and what’s more, that they are loved.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.