Reviews

George Stevens

USA, 1956

Credits

Review by Glenn Heath Jr.

Posted on 30 April 2013

Source DCP projection

Categories TCM Classic Film Festival 2013

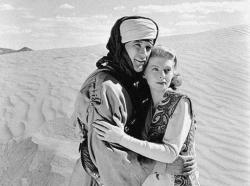

Texas cattle baron Bick Benedict and Maryland debutante Leslie Lynnton fall in love during their first quarrel. The disagreement revolves around nothing less than the historical and cultural sanctity of the Lone Star State itself, specifically its troubling origins involving the prolonged and violent displacement of Mexicans in favor of white settlers. Heavy subject matter for two doe-eyed young characters who’ve been shooting knowing glances at each other for an entire day. What’s most interesting about their frank war of words is that Leslie’s thunderclap of criticism stems not from Eastern judgement or resentment, but her seemingly organic attraction to the tall and studly rancher visiting her family’s expansive rural abode to purchase a prized black stallion. It’s a form of flirting that also acts as progressivism, challenging Bick to consider his own social identity and personal values while also arousing his romantic interest. Needless to say, the dude is knocked out cold, simultaneously head over and heels and enraged.

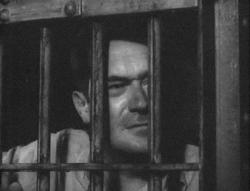

During their decade-spanning relationship that follows, always the gripping center of George Steven’s massive melodrama Giant, Bick and Leslie become masters in locking horns and making up. It’s a long and winding process that ultimately allows both stubborn characters to grow together despite the countless bumps along the way. This blisteringly fresh approach to relationships, and the organic buildup of arguments, justifies Stevens’ epic running time, much of which is spent in the presence of sassy Texans verbally sparring over matters of the heart and conscience. Topics as diverse as capitalism, land ownership, sexuality, interracial coupling, racism, and alcoholism define the lives of Bick and Leslie, not to mention their offspring, friends, and enemies. With this many issues brimming beneath the dusty wind-swept Texas landscape, there’s a palpable uneasiness to almost every character’s tortured existence. This is most noticeable in the lowly ranch hand turned billionaire oil tycoon Jett Rink, who, as played by James Dean, looks as if he were constantly trying to find comfort in his own skin.

While the men of Giant find themselves riddled with guilt and often lack the communication skills to overcome crippling low self-esteem even as they are spoiled with riches, Leslie is never not a woman of action and revision. A ravishing yankee firecracker swept off her feet by Bick and transplanted to an endless horizon of cattle fields, she is as pragmatic about the gender inequality of her surroundings as she is furious with its limitations. One of Giant’s great scenes finds Bick and his cronies huddled around a wood table discussing important matters while their wives sit quietly together sipping bourbon in the corner of the room. The separation is set in stone by Stevens’ wide angle composition. But Leslie breaks the barrier when she casually walks over and begins listening to the political debate. The men instantly stop talking and look to Bick, who’s equally aghast at his wife’s trespassing and scolds her for it. In turn, Leslie unloads a brilliant sarcastic attack against the men and their dedication to outdated modes, calling into question a gender structure firmly rooted in inequality.

The little moments matter in Giant, a film that despite its title, running time, and girth, values a return to a smaller worldview, especially in its scathing indictment of modern day capitalism. “Big stuff is old stuff,” one character says. Yet, when it comes to emotional expression, the inverse is true. Giant firmly understands the need to destroy those social limitations put upon by bigotry, hate, and class division. From Leslie’s desire to improve the living conditions of her Mexican workers to Bick’s knockdown drag out fight with a racist inside a roadside diner, the film’s most stirring subplots concern this kind of reformist action. Stevens elevates these moments even more when he allows the characters consider the gravity of their actions devoid of any self-congratulation or ego. For them, togetherness is paramount.

Consider Giant’s final sequence, where Bick and Leslie sit together in their ranch house reflecting on the past, the present, and the future of their serpentine family tree. Now weathered by time, gray hair and all, the couple stares at their grandchildren (one white, one half-Mexican) and reminisce. When it comes to their children’s future, something they’ve argued over incessantly throughout the film, the conversation turns wonderfully enlightened: “All you can do is raise them.” If their love affair was born in the heat of an argument so many years before, Leslie and Bick fade to black at peace with the inevitability of life’s curveballs, ready for whatever comes their way, side-by-side. If Giant teaches us anything, it’s that the true American dream is rediscovering the simple life, and all its glorious complexities.

More TCM Classic Film Festival 2013

-

Hondo

1953 -

The Narrow Margin

1952 -

Giant

1956 -

The Razor’s Edge

1946 -

The Desert Song

1943 -

Try and Get Me

1950 -

It

1927 -

Scarecrow

1973 -

They Live by Night

1948

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.