Reviews

Pisma myortvogo cheloveka / Dead Man’s Letters

Konstantin Lopushansky

USSR, 1986

Credits

Review by Ian Johnston

Posted on 19 August 2013

Source TV broadcast dub

Categories Favorites: The Apocalypse

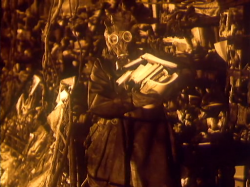

With its very first shot Letters from a Dead Man lays down its aesthetic and thematic concerns. From a close-up on a naked light bulb - to a background of ominous rumbling and suffused in a sickly yellow light that’s courtesy of a yellow filter in use in almost every scene of the film - the camera glides down to a sick woman, pulls back to reveal an elderly man sitting beside him, then dollies further back in a series of shifting movements as the man sits at a table and begins a letter to his son: “Dear Eric….”

We’re in the aftermath of the nuclear holocaust, or, at the very least (the fate of the wider world is implied rather than made clear), of the destruction of this city in a nuclear attack. Outside the city lies in ruin, the air poisoned with radiation, bodies still lying in the rubble-strewn streets. Those still alive in this nuclear winter are sheltering in bunkers - which in the case of our protagonist, only ever identified as “the Professor”, takes the form of the basement of a museum. Here the Professor and his wife have found shelter with the remnants of the museum staff. The staff themselves are never named (at least not in the English subtitles) and include a writer/researcher still dictating his work to a woman who is perhaps his wife, and another scholar and his adult son.

The city’s now under martial law: we see the Professor playing dead to hide from a patrolling helicopter that sweeps over the devastated cityscape and then, soon after, escaping from a military raid on a black market. Earlier, his visit to an orphanage run by an elderly pastor reveals the plans of the military government to move all healthy survivors into a central bunker. A doctor is there to issue passes to those who qualify—which the children, without parents and shocked by their experiences into a catatonic silence, do not; nor may the pastor if he proves to be too old. This is the brutal pragmatism of the new post-apocalypse society, whose amorality the film’s humanism finds wanting and which is acknowledged by the physically and morally exhausted doctor but which he cannot or is not willing to do anything about.

You don’t need to know that director Konstantin Lopushansky, whose first feature Letters from a Dead Man was, worked as production assistant on Stalker to still recognise a heavy Tarkovsky influence on the film’s style. It’s there in the lengthy takes; in the awesome beauty to be found in devastated landscapes (one close-up of detritus floating on oil-slicked water even seems a direct quote from Stalker); in the intensity with which the camera gazes upon the human face in extremis; in the Christian underpinnings to the story; and in the way, as with Stalker and Solaris too, it takes a science-fiction setting to offer some very explicit ruminations on the nature of Man. Still, this is not unalloyed Tarkovsky; Lopushansky, like Sokurov, the other great Tarkovskian disciple, has created his own personal film world. The narrative’s more straightforward than you get with Tarkovsky, the colour tinting is more obviously motivated by story and setting, and while Lopushansky lacks Tarkovsky’s sublime moments of ineffable, mysterious transcendence, on the other hand he certainly has more of a sense of humour. There are a number of blackly humorous notes: responsibility for the nuclear attack is blamed on a computer operator slowed down by the cup of coffee in his hand; in the museum the aural background of the writer’s dictation of his weighty thoughts is incongruous and ineffectual, however apt some of those comments might be; and the woman’s theory of going naked to accelerate her adaptation to the radiated environment is simply ludicrous. But even more critical to the film is the scene where the Professor ventures out to visit a scientist friend in his own bunker. The friend cracks a stupid joke and the two collapse into each other’s arms in laughter, the only sane and human response to their situation.

The end-credits provide a lengthy quote from the Russell-Einstein Manifesto of 1955 (a plea for nuclear disarmament signed by Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, and nine other prominent scientific worthies of the day) and offers thanks to the Committee of Soviet Scientists for Peace and Against the Nuclear Threat. As such it’s a true product of the 1980s and the resurgent fear of nuclear war that found expression in any number of phenomena, from the revived strength of CND in the UK to the myriad of TV and film productions that dealt seriously with the issue (Threads, The Day After, Testament, When The Wind Blows, and so forth). On one level the film warns against the horrors that will be inflicted on mankind by nuclear war. Midway through Lopushansky positions a flashback to the attack itself, a powerful sequence of the city engulfed in fire that includes one striking shot of the burning cityscape played off against two voices, an operatic solo and the murmurings of a child. The emotional climax to the sequence is the Professor’s frenzied search for his missing son where he is confronted with the screams from a hospital ward full of child burn victims and he ends up slumped against a wall, a stream of water trickling down onto his head and then down his body.

For all these depictions of the horrors of nuclear war, Lopushansky is as much concerned with seeing what defines humanity in this moment of crisis. In the museum the father and son play off one another. The son proposes that a new mankind is being born underground, a new impersonal morality of the hatred of self and other; the father later counters with an elegy on mankind of the past, a mankind capable of compassion and love even when that conflicted with the logics of survival. And this is an elegy on the past, for the father, after making this heartfelt speech, retires to kill himself.

“You’re the last humanists. Like mammoths,” the son accused his father earlier, and the film is clearly on the side of these old men who refuse the new dispensation. “I don’t believe there is no outside,” says the Professor, refusing to believe that all life on the surface of the Earth has been extinguished, and in the end he similarly declines to join the others in moving to the central bunker, staying behind instead to care for the catatonic children. Obviously, this is his death sentence, yet through his mentoring of the children - teaching them, for example, the rituals and meaning of the Christmas tree - Lopushansky ends the film on a hopeful note. On a logical level, the children, gas-masked and leading one another off into the frozen wastes, can only be walking to their deaths. But this has been framed by a child’s voiceover with Biblical overtones, read as if it were a narrative from the future: “And on the sixth day of the beginning of the world’s end Teresa led them to another place like the pastor prophesied…” The final words of the film are the dying professor’s legacy to the children, to set off on their own search though a world that cannot have died: “While a man is on his way, there is still hope for him.” The final images are an expression of that hope.

More Favorites: The Apocalypse

-

The War Game

1965 -

On The Beach

1959 -

Where Have All the People Gone

1974 -

A Boy and His Dog

1975 -

Bug

1975 -

La Soufrière

1977 -

Escape from New York

1981 -

The Road Warrior

1981 -

Le Dernier Combat

1983 -

Night of the Comet

1984 -

Threads

1984 -

The Terminator

1984 -

Def-Con 4

1984 -

Letters From a Dead Man

1986 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Last Night

1988 -

Last Days

2005 -

The Rapture

1991 -

Southland Tales

2006 -

Idiocracy

2006 -

The Happening

2008 -

The Road

2009 -

Cosmopolis

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.