Reviews

Jerry Schatzberg

USA, 1973

Credits

Review by Veronika Ferdman

Posted on 14 May 2013

Source DCP

Categories TCM Classic Film Festival 2013

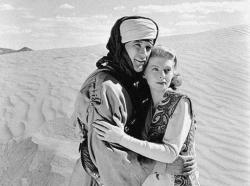

If one could proclaim a film a masterpiece based solely on the strength of its performances, then Jerry Schatzberg’s Scarecrow would certainly be one. The film depicts the relationship between Lion and Max, vagabonds who team up on the road en route to Pittsburgh (on the way to which Lion seeks to make amends for having abandoned his pregnant girlfriend). The plan is to set up a car wash there, an idea which Max repeatedly discusses, as if sheer force of repetition will bring it into being.

As portrayed by Al Pacino and Gene Hackman, the pair is rendered with a certain magnetism: Pacino’s Lion a playful and clownish satellite looping around Hackman’s more stable and grounded Max. Lion wins over the initially unfriendly Max by making him laugh and offering him his last match so that Max can light his cigarette. Lion tells Max that the reason crows avoid farms that have scarecrows is not because they are frightened, but rather because the scarecrows make the winged observers laugh. And so the crows take mercy on those farmers. Lion thus encapsulates his approach to life, urging Max to adopt his attitude. Laughter vs. fear and violence is the film’s key conflict, from which the title derives its poignant significance (recalling The Catcher in the Rye’s for its overwhelming humanistic beauty).

The journey in Scarecrow (from Bakersfield, California to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania) is not just a physical one, but one of self-discovery, inciting role reversals and the arrival upon a keener sense of self (at least for one of the principle characters). Certainly this is not a new trope for a road movie, as the genre often eagerly uses the physical space of a journey - highways, train tracks, cars, hotel room, diners - as an excuse against which nebulous existential crises are unraveled. And Scarecrow fits snuggly into the genre without much deviation.

However, the trouble with the film lies in Schatzberg’s predilection for over-emphatic visual clues that betray any joy in scanning the frame for bits of information when, for example, a camera zooms and meaningfully lingers over a specific object. When Max, who usually wears many layers of clothes (because he claims to always be cold), enacts a jokey striptease in lieu of throwing a punch as he normally would, the action’s metaphor is all too clear: he is shedding the skin of his former, more violent self.

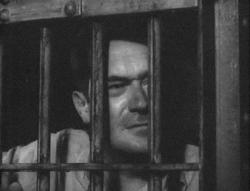

Furthermore, the homophobia is hard to stomach. When Max and Lion are thrown in jail, a man who is at first friendly and sweet beats Lion brutally after Lion refuses to perform fellatio. Scarecrow rhapsodizes masculine friendship as long as it remains strictly platonic. There’s no infusion of homoeroticism, only a valorization of heteronormativity.

More TCM Classic Film Festival 2013

-

Hondo

1953 -

The Narrow Margin

1952 -

Giant

1956 -

The Razor’s Edge

1946 -

The Desert Song

1943 -

Try and Get Me

1950 -

It

1927 -

Scarecrow

1973 -

They Live by Night

1948

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.