Reviews

Robert Florey

USA, 1943

Credits

Review by Glenn Heath Jr.

Posted on 03 May 2013

Source 35mm print

Categories TCM Classic Film Festival 2013

The introductions at TCM Classic Film Festival are often the most revealing portion of the filmgoing experience. So it wasn’t a good sign when, during his pre-screening speech, iconic television host Robert Osborne spoke this fateful line of Robert Florey’s 1943 version of The Desert Song, a film that hasn’t seen the light of day for 50 years due to rights issues: “It’s not a great movie, but it’s a fun one.” Well, he was half right. Released during the heart of WWII, this choppy adventure/musical is most interesting when seen as a blatant guilt trip made by Hollywood to remind European pacifists of their indifference during the swelling Nazi threat in the mid-to-late 1930s. As a classic genre film, it’s an inconsistent and inert Casablanca clone.

Set in sultry Morocco circa 1939, The Desert Song revolves around clashes between a local insurgency of tribesman known as the Riff and French imperialists over the construction of a pan-Saharan railroad funded in secret by good old Adolf. Early in the film’s short prologue, a French spy returns to Paris and informs his superiors that the Germans are indeed conducting an act of industrial subterfuge, creating a key supply line that will connect North and West Africa. His claims are laughingly dismissed as “alarmist.” Covert information is king in The Desert Song, yet it’s astonishing how many times the censorship and dismissal of said secrets plays a pivotal role in advancing the operatic plot.

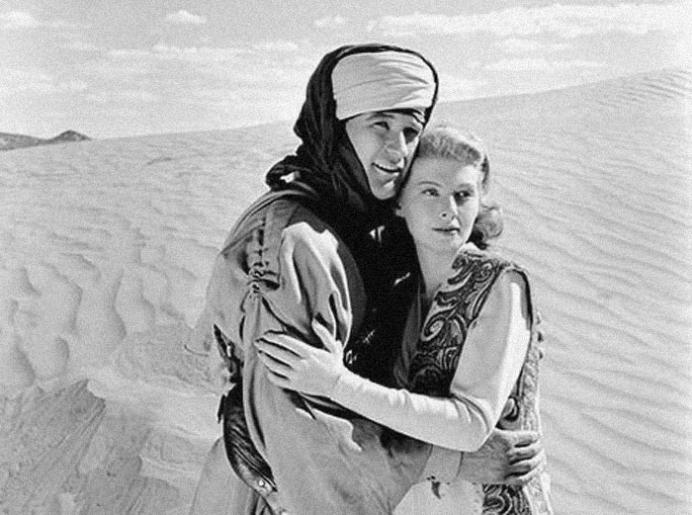

The Riff rebellion is made up of a tenacious group of freedom fighters led by the mysterious El Khobar, who in a not so subtle twist ends up being an smooth-talking piano player named Paul Hudson. Having an expat lead an Arab guerrilla outfit is a fascinating prospect considering the last century of American foreign policy, but The Desert Song is not interested in any form of genre as subversion. Its thematic goals are consistently straightforward, never wavering from finger pointing at French apathy/ignorance and yankee gallantry, which inevitably becomes stale after a while.

In a soapy film this flushed with forced musical numbers (we get contrasting performance pieces by two women of different nationalities), redundant chase sequences, and poorly blocked shootouts, it’s easy to notice certain joyous threads on the fringes. Paul’s older sidekick is a lush journalist named Johnny Walsh who is perpetually trying to get the latest scoop to his wire service in Paris. His efforts are stunted at every turn by a nebbish censor officer, and their wonderful disagreements set the stage for one classic dialogue exchange after another, showing off actor Lynne Overman’s talent for machine-gun banter. “In a dogfight, you don’t stop to examine the pedigrees,” Johnny cleverly sneers after taking a sip of booze, inadvertently commenting on the inherent brutality of the narrative which Florey gleefully glosses over.

But to expect a prequel of The Battle of Algiers out of a flimsy slice of propaganda like The Desert Song would be misguided. Corruption, race, religion, and terrorism are all facets of the film’s arc, yet these ideas are constantly muddled, pushed to the background by an unconvincing central romance between Paul and a French lounge singer named Margot and various shifts in the action that further amplifies an already convoluted story. The film attempts to create a picture of heroism and sacrifice in the stiflingly hot desert mise-en-scene, but this melodramatic slice of American interventionism is nothing more than a mirage.

More TCM Classic Film Festival 2013

-

Hondo

1953 -

The Narrow Margin

1952 -

Giant

1956 -

The Razor’s Edge

1946 -

The Desert Song

1943 -

Try and Get Me

1950 -

It

1927 -

Scarecrow

1973 -

They Live by Night

1948

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.