Reviews

John Cassavetes

USA, 1976

Credits

Review by David Carter

Posted on 16 March 2012

Source The Criterion Collection DVD

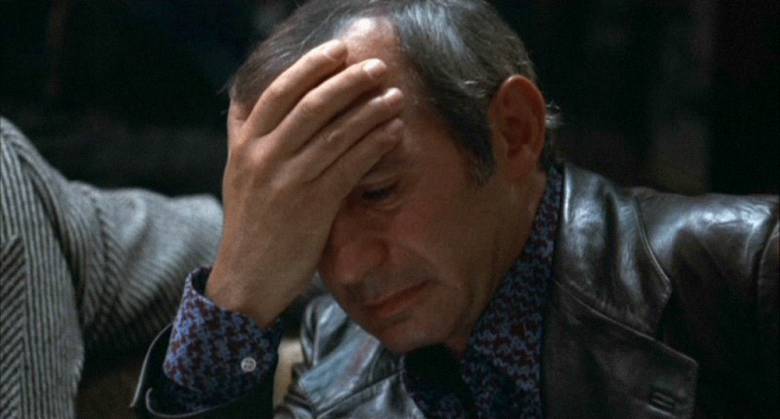

Cosmo Vitelli thinks very highly of himself. This is evident in the first scene of John Cassavetes’ The Killing of Chinese Bookie, where Vitelli castigates a loan shark for being “a lowlife” and having “no style,” and, indeed, there is a noticeable disparity between the two men. The loan shark’s simple shirt and jeans combo and meal of coffee and cake is a marked contrast to Cosmo’s all-white suit and expensive cigar. There is a disconnect between their appearances and the roles they are playing in this scene, however. It is the loan shark that has all the power in this exchange. Cosmo is there to pay off a large debt to him, and the loan shark merely laughs off Cosmo’s insults. Vitelli seems genuinely annoyed and disappointed by the situation, but not for the obvious reasons. He is upset because the exchange has no drama, no elegance, and, to use his words, “no style.” Vitelli has a way in which he views the world that is at odds with reality, and it is the violent reconciliation of his fantasy and reality that forms the heart of The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. He is a man of “style,” not substance, and his confrontation with characters that are his opposite leads to the destruction of his life.

Vitelli is the owner of the Crazy Horse West, a strip/burlesque club that is the center of his world and his de facto home. Cosmo has designed the acts - humorous musical routines starring “Mr. Sophistication and the De-Lovelies” - and oversees the entire operation down to the most minute detail. In short, he is a man who is in complete control of his world and everything in it. He is living in a fantasy world, however, one in which he has more power, money, and influence than his shoddy nightclub, aging comedian, and second-class showgirls actually provide him.

The events of the film are set in motion when illegal casino owner Mort Weil comes to the Crazy Horse on a slow night and praises Cosmo, playing into his grandiose fantasies by telling him he has “the best club west of Las Vegas” and inviting him to come to his club where he will be treated like a king. Cosmo takes him up on the offer, arriving in a rented limousine, decked out in a tux and with his three dancers on his arm—a noticeably out-of-place sight in the low-key club. Unbeknownst to Cosmo, Mort is actually in the mafia, a fact that becomes strikingly clear once Cosmo racks up a twenty-three thousand dollar debt. “It’s only money,” he remarks while playing poker, but it is more than simply money to his creditors, who force him to sign over a stake in his club to secure his sizable debt.

Thus at the film’s midpoint Cosmo is in the same position we see him at in the film’s beginning, although his charm will be of little use this time. Mort and his fellow mobsters, including the peerless character actor Tim Carey in one of his last roles, take a special interest in Cosmo, paying him frequent visits to check on their “investment” in his club. The felonious assignment of the film’s title falls to Cosmo as a means by which to settle his account with the gang, and through this the last remaining vestiges of his constructed fantasy world are shattered. Mort’s mob is as unglamorous as the bloody task they force on Cosmo, and the internal conflict he experiences is as much due to the hard dose of reality he receives as it is to knowing he’ll have to commit murder. The “killing of a Chinese bookie” is, as to be expected, a set up; the mob does not expect him to return. When he does, Cosmo is forced to desperately try to hold on to the increasingly fragmented shards of his life as the mob tries to tear it apart.

Cosmo’s fantasy is to some degree shared by the audience, and Cassavetes subverts the wishes of both, particularly through the depiction of the mob. As mentioned, this is a decidedly unglamorous depiction of organized crime; Cosmo’s earlier insult of “no style” would be apt. One must bear in mind the context in which The Killing of a Chinese Bookie was made, a time in which the mafia had been redeemed and glorified by Coppola’s The Godfather I and II. The film’s de facto villain, Mort, is more accountant than Corleone and one is left with the impression that Cosmo is more disappointed that mobsters don’t adhere to his personal sense of taste and style than he is afraid of the prospect of dying. The uncinematic nature of his tormentors and, later, his murder of the bookie do not trouble Cosmo in and of themselves, but rather because they shatter the illusion of his life.

It must be mentioned that The Killing of a Chinese Bookie is actually two films: the original 135 minute version released in 1976 and the re-edited, 108 minute version released in 1978. As the longer of the two was Cassavetes’ original vision of the film, I have used it to form the basis of my remarks here. The differences between the two prints are too numerous to fully detail in this space, but I will make note of the primary point of variance between the two, which is the inclusion of performances from the Crazy Horse. There is a clear connection between Cosmo’s character arc and that of Mr. Sophistication. Both have a considerably high - and mostly undue - assessment of their own worth, and both are ultimately made to be buffoons through the course of the film, Cosmo by the mob and Mr. Sophistication by the dancers. This is an important aspect of the longer version of the film, but I find myself agreeing with the decision to remove them. The point is made very early on and only becomes belabored as the film progresses, eventually becoming a distraction to the main narrative. Furthermore, Cassavetes’ direction lends a good deal of tension and dramatic weight to Cosmo’s struggles with the mob, but it begins to border on pretension in the filming of the cabaret scenes.

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie remains a complex film regardless of which version you consider. It is perhaps the least critically successful of Cassavetes’ work, and the criticisms laid against the film (including those by star Ben Gazzara) are not meritless. There are moments of tedium. There scenes that go on for too long, and some that are far too short. There are moments of brilliance also, however, both from Gazzara as well as the supporting cast. It will be difficult to make an immediate connection with the character of Cosmo Vitelli, putting the film at a disadvantage since he is the only focus. But a closer study of the character reveals a man that is begrudgingly likable and not wholly dissimilar from ourselves. He is a man who has his dreams stolen from him by forces beyond his control. It was a very personal statement for Cassavetes, and one that many viewers will perhaps find uncomfortably resonant.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.