Reviews

Paul Thomas Anderson

USA, 2012

Credits

Review by Adam Balz

Posted on 25 September 2012

Source 70mm print

The mystery is that even if we know that it’s only staged, that it’s a fiction, it still fascinates us. That’s the fundamental magic of film. You witness a certain seductive scene, then you are shown that it’s just a fake, stage machinery behind, but you are still fascinated by it. Illusion persists. There is something real in the illusion, more real than in the reality behind it.

—Slavoj Zizek

There’s a moment early on in Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master - I’m not sure of the specific scene exactly - when I began to feel uncomfortable. This sudden, uneasy feeling had nothing to do with the theatre I was in or the production value of the film itself—both were excellent. Instead, this feeling, which I can best describe as a headache minus the pain, was drawn from a feeling that I was somehow having my mind manipulated, that I was being slowly and carefully brainwashed, until I was fully and suddenly under the thumb of a mysterious cult. And, as it turns out, I was. Over the course of two hours, my mind was slowly, methodically, skillfully twisted by Anderson himself, only there was no cult like the one being depicted in his film. Rather, Anderson’s cult was that of cinema, pure and simple—the delicate, century-old art of blurring the line between what is real and what is imagined until you are lost in the in-between.

This theme is present almost immediately when the film opens on a Pacific island during World War II. There, a squadron of men idle away their time until they can fight—a promise that will never come to be realized. Instead, they wrestle one another on the beach, swim, exercise, and ultimately build a naked woman out of sand. This is not the World War II we’ve come to know as part of our history, not to mention of our war cinema; there are no traces of John Wayne’s Iwo Jima, of the battles fought in the pages of Stephen Ambrose, the reels of Steven Spielberg, or the interviews of Ken Burns. Instead, this is the reality that many men experienced—seemingly endless periods of boredom conducted in exotic locales. These stories, however, are not the glorious tales of war we expect for our fighting men, and so history itself has dropped them in favor of a fantasy in which every man fought in dirty ditches under gray skies—the fantasy of glorious, unyielding violence and self-sacrifice and saccharine letters from home. Here is the reality, in lieu of the fantasy.

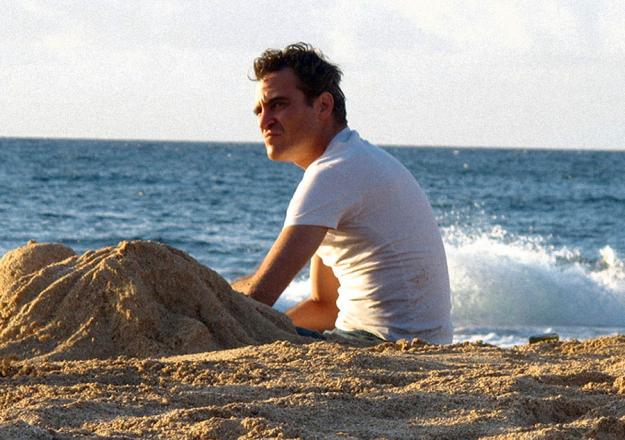

It’s on this island that we’re introduced to Freddie Quell, Anderson’s protagonist and the pivot between reality and fantasy. It’s Quell who, coming upon his fellow soldiers’ sand-woman, proceeds to simulate sex with it; later, he will return and lie alongside it almost tenderly, romantically, as though the sand form were more than just a cold shape beside the ocean. When the war ends, Quell moves from place to place, unable to hold down a job due to his violent temper and rampant alcoholism. After stowing away on a boat, he’s introduced to Lancaster Dodd, a charismatic and self-described Renaissance man who leads a pseudo-religious movement known only as the Cause. As it turns out, Dodd is himself a stowaway of sorts: this is not his boat, and he’s leaving behind a mainland where authorities have begun to scrutinize and persecute him. His Cause is a thinly veiled cult based on the idea that, while under a sort of hypnosis, anyone can travel back into previous lives, often a trillion years back, and find the source of pain and suffering. It’s an idea that Quell seems to view as more of a parlor trick at first - a fun way to test his own physical and mental stamina - but soon comes to see as having promise. The two men become close, seemingly joined by their status as outsiders searching for a purpose; it soon becomes apparent, however, that Dodd and Quell have more in common than they realize, even as Dodd takes up the role of “Master” to Quell’s patient and right-hand man.

Throughout the film, the camera frames both men as complementary opposites, almost like two puzzle pieces who fit together perfectly: Dodd, whose fantasy life masks a core burning with rage and indignation, against Quell, who yearns for a life of fantasy to mask the life of anger he’s come to know as normal. In fact, Quell’s life is a series of fruitless and self-satisfying “causes” - serving his country, following Dodd, defending himself, getting drunk - that only add to his misery and loss of purpose. Where Dodd is constantly surrounded by adoring followers, Quell has no one. Where Dodd is a short, squat man, Quell is thin and lanky, shoulders hunched forward, his frame often looking as though it were being swallowed up by his clothes. Dodd has the power of words, able to sermonize at will on any subject, while Quell’s lack of social skills render his conversations short and awkward, often punctuated by vulgarities. At time it almost seems as though Quell looks at Dodd as the promise of himself, that Dodd is the man Quell would like to someday be.

Unfortunately for Quell, this kind of aspiration, not to mention every promise of reform delivered by Dodd and his Cause, involves Quell abandoning the reality of his situation and descending into a manufactured life. As Quell spends more and more time at Dodd’s side, his footing in reality begins to slip, and the film becomes increasingly dominated by clashes between the real and the fake. In an early scene, Dodd asks Quell to queue up memories of his girlfriend following an interrogation in which Dodd forces Quell to abandon vainglorious lies - he killed Japanese soldiers - in favor of ugly truths—he poisoned an old man, he had an incestuous relationship with an aunt. This moment is followed by scenes in which Quell imagines Dodd dancing among naked women at a meeting for members of the Cause; Dodd’s wife, played by Amy Adams, attempting to cure Quell of his vices by reading a pornographic story in a dispassionate, almost monotonous tone; Dodd confronted by one of his most ardent followers over a seemingly minute change in text that encourages patients to “imagine” their past lives rather than “remember” them; and Quell forced to pace back and forth between a wall and a window, his mind concocting increasingly unbelievable alternatives for both. And, in one of the film’s closing scenes, Quell dreams of receiving a phone call from Dodd while at the movies. It’s the first tangible dream we see Quell having, the first moment in the entire film when there’s an obvious and undeniable lapse into fantasy, and it’s in this moment - he is in the theatre receiving a phone call, he is in the theatre waking from this dream - that Quell becomes utterly lost.

The fact that this scene occurs in a movie theatre is not coincidental. Cinema is, after all, the place where people go willingly to suspend their beliefs and embrace manufactured realities with ease. Year after year, moviegoers place their faith in unseen men and women - writers, directors, producers, actors, set designers, and so on - who work together to essentially fool millions of us into believing, even for a few hours, in a world projected onto a screen. The places beyond the theatre walls disappear, the tensions in our lives fade away, and we offer up ourselves to worlds with careful edits and scripted interactions. And we don’t question this even slightly—we just accept it, even discussing it on the merits of its verisimilitude after the fact, seemingly unaware that we’re criticizing films when the fantasies they present aren’t real enough for us. It’s this dichotomy that Anderson uses to end the film. Quell, having left Dodd’s Cause for good, shares two separate moments with women. The first is the mother of his former girlfriend, and in this scene we see the awkward, uncomfortable Quell who began the film, the Quell grounded - some might say trapped - in reality; in the other, we see Quell in bed with a woman, and as they move slowly together he begins asking her the very same questions Dodd had asked during his initial interrogation, in the same repetitive way. And as this latter scene ends, the woman’s naked breast dominates the bottom-left corner of the screen in much the same way the sand-woman’s constructed breast and Dodd’s red robe did earlier in the film. It’s in these two scenes that we understand how divided Quell still is between reality and fantasy.

I saw The Master with my brother, and after we left the theatre and sat down to talk about it over a quick dinner, a curious thing happened. As we waited for our meal to arrive, he said, “Did you notice her eyes turned black?” He was referring to a scene in which Amy Adams’ character addressed the camera, meant to be Freddie’s point of view, and convinces him that her blue-green eyes are in fact purely black—yet another instance of the real being changed in favor of fantasy. I told my brother yes, I’d noticed, but in reality I wasn’t sure. Was it possible her eyes had turned darker, to black, and I’d missed it? Of course. But it was also possible my brother had imagined this transformation after the fact—that the reality of what he’d seen had given way to the fantasy that had been concocted for both of us through Freddie Quell. Amy Adams’ character tells Freddie - and us - that her eyes are black, and it’s believed, even though it isn’t true. Just as Freddie hands himself over to fantasy - of all causes, big and small, willingly and foolishly, over and over again - so do we, film after film, over and over again.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.