Reviews

Mark Moormann

USA, 2003

Credits

Review by Tom Huddleston

Posted on 23 May 2006

Source Palm Pictures DVD

Have the great rock ‘n’ roll stories all been told? We know what John and Paul, Mick and Keith, Jimi and Janis had for breakfast every day of their adult lives. Exhaustive documentaries and biopics of just about every recording artist of the past fifty years screen each night on cable, and if that’s not enough we can attend photographic and cinematic retrospectives, pick up CD and DVD reissues with bonus tracks and liner notes. Has all the mystery gone?

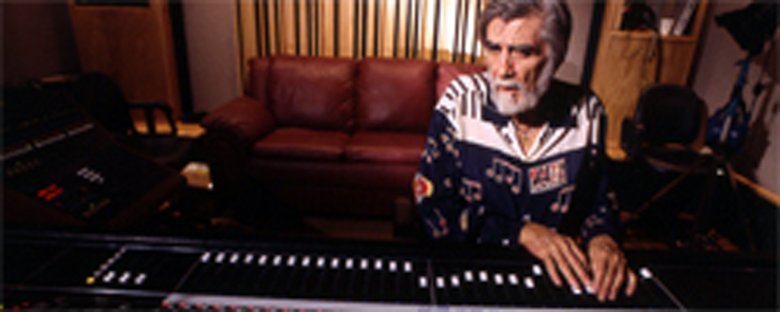

In the past few years interest has grown in the peripheral figures of popular music, the producers, the writers, the managers—documentaries on Kim Fowley and Rodney Bingenheimer, features like Almost Famous and Grand Theft Parsons have attempted to shine a light into the few remaining dark corners of this overilluminated world. Tom Dowd’s contribution to recording technology is unquestionable: he pioneered 8-track recording, worked with artists ranging from Ray Charles to Ornette Coleman to Tito Puente to Lynyrd Skynyrd, pretty much the full gamut of musical styles from 1950 to 1975 and beyond. He was the in-house engineer for Atlantic records during their heyday, and was, it seems, universally loved and respected by all who met him. But Tom Dowd and The Language Of Music is an unashamed visual hagiography more suited to VH1 than DVD, with no attempt to bring the story to life the way the Fowley and Bingenheimer films did.

There’s a wealth of fascinating information, and for those unfamiliar with the development of recorded sound Dowd’s reminiscences should be required viewing. Most of the interviews are conducted straight to camera, a simple statement of fact. But a few, most notably Ray Charles and Ahmet Ertegun, are loose and jovial, filled with personality. A scene where Dowd himself interrupts Charles mid-interview is full of warmth and undisguised respect. The central section of the film, covering Atlantic’s relationship with the Stax label in the mid ‘60’s and featuring performances and archive footage of Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin, is electrifying, the enthusiasm of the players and engineers present is contagious. But the same stories could be, have been, told before—by Bob Sarles’ Soulsville or the recent Soul Deep documentary series, placing different but equally important figures centre stage—Jerry Wexler, Ertegun, The MG’s or any of the other artists Dowd recorded. What we need is a reason why Dowd’s story is worth telling instead of or alongside those of his industry colleagues, but it never comes. Director Moormann seems largely uninterested in anything deeper than a casual reminiscence, a fond memory. At one point somebody mentions Dowd was married—this is the first we’ve heard of it, and the nameless spouse is never mentioned again. The stories start to become repetitive: “in England they were still recording with 3 tracks…”, “So Dowd came down here and right away got that board working…”. Towards the end, a near ten-minute examination of the song ‘Layla’ will be manna for Claption fans, but it’s a patience-testing indulgence for the rest of us.

The most worrying period of Dowd’s life is addressed early in the film—between the years 1942 and 1946 he worked as a physicist on the Manhattan Project, developing the first nuclear bomb. He was present at tests on Bikini Atoll, and had full knowledge of the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Admittedly, this is not the focus of the film—this is a documentary about Dowd the sound engineer. But when he asserts that he quit physics not for moral reasons but because he was already more scientifically advanced than his lecturers (and later asserts that his “conscience does not bother him”), serious questions must present themselves. Does Dowd have no regrets that his research led directly to such an horrific crime? Does Moormann have no interest in learning how his subject feels about his part in it? The subject is glossed over, trivialised, another wacky episode in a rich and eventful life. The morality here is complex, the potential questions largely unanswerable, but to refuse even to ask seems cowardly in the extreme.

In the end, this is a potentially interesting subject neutered by a director reluctant to get to grips with his subject. The title is misleading, even meaningless—very little is learned about ‘the language of music,’ whatever that might be. We gain a little insight into the (now outdated) technology, but get very little sense of the subject as a man, as an enthusiast, as anything other than a technician. Dowd was a musical visionary. He was married more than once and fathered several children before passing away in 2002. He deserves a more incisive, insightful memorial than this.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.