Reviews

Oncle Yanco

Agnès Varda

France/US, 1967

Credits

Review by Evan Kindley

Posted on 23 July 2010

Source MUBI streaming video

Categories Viva Varda: The Films of Agnès Varda

The niece wanted to show her uncle to the audience of the dark theater.”

In 1967 Agnès Varda found herself accompanying her husband Jacques Demy on an extended working vacation in the state of California. The opportunity to come to the States was provided by the surprise success of Demy’s musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg and its sequel, The Young Girls of Rochefort, which were sufficiently popular to inspire Columbia Pictures to put up money for Model Shop, a typically sweet and color-saturated English-language melodrama set in Los Angeles and starring Anouk Aimée and Gary Lockwood. Like her husband, Varda also captured her reactions to their strange new milieu on film. But where Demy made a relatively high-budget studio picture, Varda used the opportunity to bring the experimental documentary techniques that she, Chris Marker, and other Rive Gauche filmmakers had begun to develop in France to the New World. Uncle Yanco is the first of the films Varda would make in California, and it’s also the most obviously personal, in that it records her first encounter with her uncle Jean (actually her cousin’s father, as she notes in the film, but why quibble?), a painter living on a houseboat in the “aquatic suburbia” of Sausalito, just across the bay from San Francisco.

Uncle Yanco is a seventy-four year-old man with a small white handlebar mustache and a barrel chest squeezed into a bright pink sweater; his great claim to fame, and to Agnès’ previous attention, was being the subject of a 1947 profile by Henry Miller in Circle magazine. In one of her trademark self-reflexive gestures, Varda reenacts their first meeting on a Sausalito pier several times for the camera in as many languages, complete with slates and botched takes. In contrast to her harder-edged work of the late 60s and 70s, Uncle Yanco is a thoroughly sunny film (in every sense of that word), suffused with Californian bonhomie and Hellenic hedonism in equal measures. Though made at the height of the Direct Cinema movement in America, the film has a handcrafted artificiality, less like a live feed from a television news camera and more like a series of holiday snapshots laid side by side in a hand-stitched photo album.

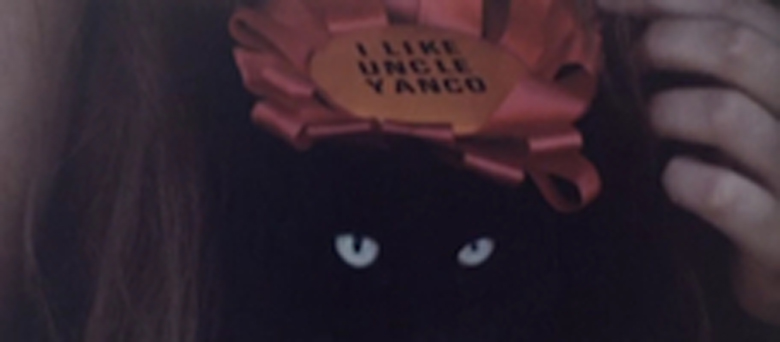

More than just an Agnès Varda film about a relative, Uncle Yanco feels like a collaboration between the two artists. They share the voiceover track (the film was shot silent, with narration later overdubbed in French and, later, again into English) and both contribute visual ornamentation to the already spectacular Northern California seaside (Jean in the form of his pastel-hued Cubist-style mosaics, Agnès with her custom-made button badges and plastic heart-shaped transparencies). Indeed, they have a lot in common besides their bloodline, like broadly leftist political sentiments (anti-authoritarian, anti-war) and a strong, if slightly bemused, interest in the youth of America. (Yanco’s houseboat is frequently overrun with starry-eyed flower children, a situation he doesn’t seem to mind: “It seems that I am a point of reference, like a lighthouse,” he chuckles. Later, Agnès puts them to work as human mannequins, posing them with buttons emblazoned VIVA VARDA placed on unusual parts of their bodies.)

The two are also on the same page with regard to their extended family, which they both celebrate and keep their distance from: “In our family they thought that an artist was a sort of outsider, a sort of clown. A delinquent,” Jean recalls, and in Uncle Yanco they both play up their clownishness and affirm it as a way of life. Here, art is not an affront to family values but an expression of it. “Imaginary families, I love you!” Agnès exclaims halfway through the film (revising André Gide’s infamous “Families, I hate you” from Les Nourritures terrestres), and the whole effort is animated by a strange, half-embarrassed sense of familial piety. The reservations about family life that Varda had already expressed so painfully in earlier films like Le Bonheur are temporarily forgotten in favor of the comforts of a home away from home.

Finally, Agnès and Jean also share a taste for spontaneous philosophical pronouncement (as what self-respecting Greco-French intellectual doesn’t?), and in summarizing his aesthetic for the camera Uncle Yanco delivers a handful of doozies: “To the eye that’s pure, the world is transparent”; “Hell is doing what you don’t like”; “For me, color is ecstasy. And everything outside of ecstasy is vanity.” In a longer film this weakness for epigram might become grating, but at a mere 18 minutes Uncle Yanco never overstays its welcome, and serves equally well as a paean to the bohemian culture of greater San Francisco — “Holy City, City of Love,” as Jean, a connoisseur of celestial cities, calls it — as it does as a meditation on the consolations of family. Both are summed up by one of Uncle Yanco’s best bon mots, albeit one that the rest of his niece’s filmography can’t entirely support: “In the kingdom of God, there are no shadows. All is light.”

More Viva Varda: The Films of Agnès Varda

-

Cléo from 5 to 7

1962 -

Le Bonheur

1964 -

Les Créatures

1966 -

Uncle Yanco

1967 -

Black Panthers

1968 -

Lions Love

1969 -

One Sings, the Other Doesn’t

1977 -

Daguerréotypes

1976 -

Mur murs

1981 -

Vagabond

1985 -

Jacquot de Nantes

1991 -

One Hundred and One Nights of Simon Cinéma

1995 -

The Gleaners and I

2000 -

Cinévardaphoto

2004 -

The Beaches of Agnès

2008

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.