Reviews

Spiral

Higuchinsky

Japan, 2000

Credits

Review by Alan Hogue

Posted on 22 November 2005

Source Image Entertainment DVD

Kirie lives in a small town. She’s a sentimental, good-natured girl. High school is tough for her, but she doesn’t seem to mind as she has no special plans for the future. She helps her widowed father with meals, dutifully goes to school, and spends a lot of time riding around town with Shuichi.

Shuichi is an affectless and repressed young man who wears his hair plastered to his head and sports thick, black rimmed glasses. He’s headed for a Tokyo university some day, and he’s impatient to be on his way.

Toshio is Shuichi’s dad. He collects anything he can find with a spiral pattern on it. He likes to spend hours quietly filming snails.

Kyoko, a classmate, has lately taken to wearing her hair curled into perfect spirals. They seem to become more elaborate each day.

And people have been dying around town lately. One student hurls himself (accidentally?) to the bottom of a spiral staircase. After a car accident, the victim’s head leaves a spiral pattern of cracks in the windshield. Soon spirals are blossoming everywhere as the town goes mad.

What’s in a symbol? This is the question Uzumaki (Japanese for “spiral, vortex, whirlpool”), perhaps the first movie I have seen to feature a geometrical shape as an object of horror, invites us to ask. The town of Kurozu-cho is mysteriously cursed by spirals. Whatever cosmic, supernatural significance the spiral has is obscure, as is the significance of being cursed by an inanimate shape.

The premise may sound goofy, but Uzumaki is on to something. It’s safe to say that for the majority of humans’ time on this planet, the natural world — including inanimate objects and even abstract shapes — has been invested with meaning and agency. Things in the outside world, and their properties, were never random or meaningless, and one did well to keep a sharp eye out for omens and hidden connections just as we begin to search carefully for the spiral figures that are hidden at random throughout the film like a perverse “Where’s Waldo.” This paranoid animism — this assumption of hidden meaning and menace in the mundane world — is a very effective source for horror films, and a film which does so in such a direct and arguably crude fashion is unusual and welcome.

To the extent that Uzumaki works, it does so by preying on this feeling of hidden coherencies in the world, by suggesting that behind the world’s vacant expression are unseen connections and meanings that we are unable to interpret properly. The characters in Uzumaki are therefore doomed by their inability to appease the inscrutable forces lurking just beyond perception. Though this is a fear most modern people probably lose little sleep over, or would perhaps deny altogether, for this reason it can be all the more effective. So the strange world Uzumaki creates does have that all-important, nagging element of recognition in spite of its ebullient and unabashed strangeness, without which it would be an empty stylistic exercise.

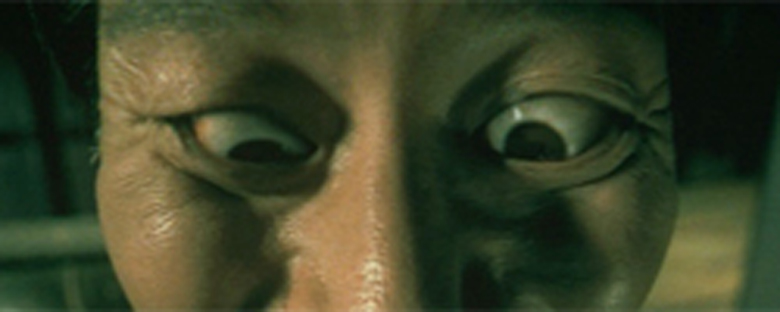

It is, I should note, a very stylish film, employing an imaginative, sometimes kinetic and often tongue-in-cheek visual idiom. Higuchinsky casts the film in green, which stylizes the color palette and makes his images almost monochromatic at times. The town is shot with a strange mixture of quaint pastoral sentimentality and latent menace: shadows are long and murky, and there is rarely direct sunlight. Inky black, ambiguous spaces are often framed just behind the character. In this way, ordinary features of the small town of Kurozu-cho are rendered simultaneously creepy and beautiful.

This is Higuchinsky’s first feature after making his name in music videos. Uzumaki does have some of the ostentatious style that sometimes mars films made by directors with such a background. But these flourishes are not as prominent as might be expected, and they don’t overwhelm the film. Uzumaki is based on a very popular manga, and it feels like the director’s concern to translate his source faithfully made him take a fairly modest approach. And, to be fair, he does share some of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s understanding of visual ambiguity and its relation to horror, at times making profoundly ominous images of real formal beauty.

One of the more interesting things about Uzumaki is that it feels uncannily like an anime, much more so than many Japanese films based directly on anime series (Uzumaki is not). This is not just a matter of visual style. Anime typically conveys emotions with the help of conventional codes, helpful before the widespread use of computer animation made detailed facial expressions possible to achieve on a tight schedule. Uzumaki is sometimes so imbued with anime conventions that it seems irrelevant to point out that it’s not animated. In some scenes, virtually every change in facial expression is accompanied by a “Huh?” “Hm!” or other vocalization. The shots and editing are anime-like as well, with fairly little camera movement but occasional bursts of manic cutting for dramatic effect. This is not so surprising, since much of the crew, including the producer, have previous anime credits to their names.

While this contradictory feeling of watching a live action animation is no small feat, it does mean that the acting style in Uzumaki is bound to deter those expecting psychological realism. While many of the actors, including the two main characters, have very little film experience, the acting is not bad—it’s just a style unfamiliar to western audiences. Still, I suspect that some viewers, especially those who dislike anime, will hate it.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.