Reviews

Werner Herzog

West Germany, 1979

Credits

Review by Martha Fischer

Posted on 05 December 2004

Source Anchor Bay Entertainment DVD

Related articles

Features: Directors: Werner Herzog

Only a matter of days after he finished work on the harrowing Nosferatu the Vampyre, Klaus Kinski rejoined Werner Herzog to play yet another tortured man. This time, he took up the role of the title character in Georg Bucher’s play, Woyzeck. Though it is a strangely powerful, fascinating film, Woyzeck is something of an aberration in Herzog’s oeuvre. The film is very theatrical in appearance, consisting mainly of a series of long takes, during which the camera is often motionless. Additionally, Woyzeck is almost completely free of nondiegetic sound, thus stripping Herzog of one of the most underrated tools in his considerable arsenal: his ability to choose music and composers. In many ways, the film belongs more to its star than its director.

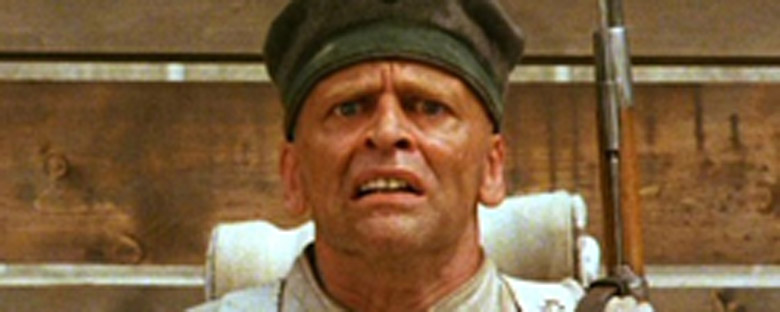

As Woyzeck, Kinski absolutely demands our attention. He is strikingly thin, clearly still suffering from the demands of the Nosferatu shoot, and the tightness of his flesh serves only to emphasize his already pronounced lips and inescapable eyes. The eyes are deeper than usual, revealing a soul so haunted and hopeless that the viewer instinctively withdraws from his character.

Though he serves as a soldier in the town garrison and has interactions with his neighbors that on the surface seem normal, Woyzeck is regarded by those around him as less than human. His terrified silence is seen a sign of stupidity, and he is thoughtlessly tormented by people from all segments of society. A local doctor pays Woyzeck to be the subject of his demented experiments, aspects of which including eating nothing but peas for months on end and not being allowed to urinate. Woyzeck suffers these horrors with only occasional, pathetic protests, all of which the doctor breezily dismisses. To Woyzeck, though, anything the doctor demands is manageable, if only because it gives him extra money to take home to his wife Marie, a “former” prostitute who continues to work under the nose of her unsuspecting husband.

Despite his ignorance of his wife’s activities, Woyzeck is nevertheless in constant, furious turmoil. Possessed by a strange sort of urgency, he is unable to simply walk the streets of his picturesque town. Instead, he moves erratically, scurrying from place to place as if afraid that something will catch him if he pauses. And, indeed, something is after Woyzeck—it pursues him everywhere he goes. He fears that the ground beneath him is hollow, and that the unseen, undefined Threat is hiding just beneath his feet. After Woyzeck learns of his wife’s infidelity, the Thing begins to speak to him, giving him a horrible direction and purpose. As it drives Woyzeck towards a desperate, inescapable end, even the wind is enlisted to aid the Thing, constantly pushing him forward with nudges and words and reminders of what he must do.

Though he willingly retreats before the power of his star, Herzog’s decision to approach Woyzeck as theater greatly enhances the film’s power. Because of the distance the camera keeps, viewers are inevitably kept at arm’s length from Woyzeck. Acting almost as a member of a theatrical audience, the camera stays out of the story, denying us the traditional tools of character bonding. There are no shot-reverse-shot conversations, and no cuts that enable the viewer to share Woyzeck’s point of view. Instead, we are forced to observe him like those around him do. No matter how much we want to understand him, Herzog refuses to let us into Woyzeck’s eyes, thus keeping us from his mind as well. Only once does Herzog allow us to share Woyzeck’s point of view and that is at what is perhaps the character’s moment of greatest weakness: when he sees his wife dancing with another man. Though the moment is powerful, the fact that we have never before been allowed so close to Woyzeck keeps us from identifying completely with his pain and, by forcing such strong emotions upon us, ultimately serves to increase our distance from him.

Even when Woyzeck escapes the torment of the town and its citizens, he remains isolated. Herzog places him in strangely sterile landscapes, so cold they resemble theatrical sets. These odd scenes serve only to emphasize the character’s isolation from the world—he can find no warmth, either among men or in nature. When Woyzeck finally performs the act that the Thing has been demanding of him, it is in one of those chilly, alien landscapes and again, we are watching. Though Herzog here allows us to creep a bit closer to Woyzeck, we nevertheless are restricted to one point of view and can see nothing but Woyzeck’s contorted face as emotions race across it. Even at this most horrible of moments, the audience is allowed no identification or even real sympathy. Instead, we simply watch as Woyzeck is rendered tragically, utterly alone.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.