Reviews

Juan Vallejo

Bolivia, 2011

Credits

Review by Katherine Follett

Posted on 14 May 2012

Source Projected DVD

Categories The 2012 Independent Film Festival Boston

In the high desert plateau of Bolivia is a mountain, Cerro Rico, that once seemed to be a pure tower of silver ore. After thousands of years of human work, almost all the silver is gone, but a large community relies on the tin, zinc, lead, and lithium that still lies in the mine-riddled mountain and on nearby salt flats. This stark economy is the subject of the documentary Cerro Rico, Tierra Rica.

This is an incredibly visual film, almost without dialogue. Director Juan Vallejo makes the most of the brutally beautiful landscape of the desert Andes. The film opens with a shot of an elderly woman’s gnarled hands, so coated with chalk-white dust that they look like stone sculptures. Other scenes seem composed entirely of sulfuric ochre, leaden charcoal, or blinding sodium white. When the film descends into the mines, it finds a world diametrically opposed to the blasted, dusty, vast surface—black, moist, cramped to the point of bumping the camera. Though more than once I wished the movie had been shot on film instead of digital video, these scenes inside the tunnels make obvious the advantages of a small setup.

While nature is a powerful and overwhelming backdrop, the work of people is everywhere. Even as the viewer marvels at the alien landscape, the labor is shockingly human. There is no heavy equipment on Cerro Rico. Ore gets chipped, shoveled, and hauled away by hand and in small, human-powered carts. Men stuff a wall with sticks of dynamite, eyeball the fuse length, and then scramble away through tiny tunnels as best they can, counting the explosions to make sure everything fired okay. The tunnels themselves are big enough to squeeze through one man at a time and no more. Though nothing dramatic happens on film, debilitating accidents must be inevitable. Even without incident, it’s exhausting work that quickly breaks down a body. We see this in the work, in the bent and broken bodies of the elderly, and in interviews with the citizens of the nearby settlement, Potosi.

The mines seem to be the only thing in Potosi, and mining is almost the only thing in this film. We don’t hear very much about the interior lives of the people who slowly chip away at the mountain or dig into the endless salt flats. The silent, meditative tone of the film allows the viewers time to speculate, but very little is verbalized. There are a few breaks from the tone of cool observation. We watch the miners socializing in an underground lunch break with coca leaf and ceremonial booze. We hear a longer-than-usual interview with a rare female miner who got the right to take her husband’s place after he died. We get a glimpse into the home of a young woman whose father and husband both work in the mountain; she believes the same life awaits her toddler son.

The film feels inescapable in every sense; the labyrinthine tunnels of the mine, the isolation of Potosi, the inevitability of life in a town with only one livelihood. But the people of Potosi are remarkably free of despair. The sense one gets from most of the interviewees is a shrugging acceptance. It turns out that though they perform incredibly difficult, tedious, and dangerous work, many of them actually own a stake in the mountain, and so have some hand in their own fate. We also learn that much of the mineral wealth of the Potosi region stays in the Andes. These small pieces of dignity, along with the sheer beauty of the landscape, save the film from despair as well. But it is still a claustrophobic, immersive, and weighty experience, like a journey within the earth itself.

More The 2012 Independent Film Festival Boston

-

Beauty is Embarrassing

2012 -

Gregory Crewdson: Brief Encounters

2012 -

Sleepwalk with Me

2012 -

Liberal Arts

2010 -

Burn

2012 -

All-Ages: The Boston Hardcore Film

2012 -

Polisse

2011 -

Sun Don’t Shine

2012 -

Headhunters

2011 -

Cerro Rico, Tierra Rica

2011 -

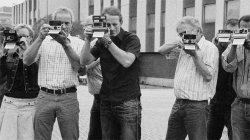

Time Zero: The Last Year of Polaroid Film

2011 -

Jason Becker: Not Dead Yet

2012 -

Detropia

2012 -

Girl Model

2011 -

Under African Skies

2012 -

The Central Park Effect

2012 -

Paul Williams: Still Alive

2011 -

Trishna

2012 -

The Queen of Versailles

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.