Reviews

Tony Williams

Australia, 1982

Credits

Review by Jonathan Foltz

Posted on 17 October 2012

Source Virgin Visi

Categories 31 Days of Horror IX

In a genre dedicated to deft manipulations of psychological space, teasing crests of dramatic tension, and the emphatic use of point of view (whether the victim’s or the killer’s), everyone implicitly understands that form is hugely important in horror films. Why is it, then, that horror films rarely feel richly formalist in their ambitions? The lines that separate successful executions of genre conventions from films of singular vision and menace are thin and extremely porous, of course. But then why does it feel so good, and so rare, to stumble upon a horror movie that doesn’t just feel in command of its images, but uniquely risky as well? Next of Kin, the 1982 spook-fest from the Kiwi-born director Tony Williams, is the best kind of surprise: it combines the campy pleasures of 80’s B-horror with the baroque composition and exacting sensibility of The Shining, Suspiria or Don’t Look Now. Next of Kin has deep resonances with these prior films, but stakes a territory that feels confidently original, carving out spaces of surrealist reverie and slow-motion lyricism in moments of ostensible panic. Still, it never feels condescending to its genre—as if horror could only be made artistic by departing from its core conventions. Genuinely obsessed with the gross liquidity of the human body - the wrinkled pallor of drowned skin and the unreal glassiness of eyes —Next of Kin finds a delicacy in the grotesque that feels traumatic rather than affected. Full of startling imagery and pulsing with a fantastic score from ex-Tangerine Dream member Klaus Schultze, it’s a film of disarming beauty about the visceral fear that adulthood is mad, violent, and wrong.

Next of Kin is the story of Linda Stevens, a young woman who has returned from school to her hometown in rural Australia on the event of her mother’s death to run the nursing home that is housed in the family estate. Although the estate, Montclare, is her childhood home, Linda feels out of place, “unwelcome,” as she confides to her old flame, Barney (played here by the wonderfully roguish John Jarratt). We don’t really know much about what Linda has been doing prior to the beginning of the film, off at a school “for emotionally disturbed kids,” but this backstory may hint at a reason for her wary reception. Linda’s composure suggests that she had been a teacher or a caregiver there, but later events in the film suggest that she may have some disturbances of her own to contend with. “What do you expect after so many years?” offers Barney in an attempt to be consoling. “No letters, no phone calls. People are curious, that’s all.” In any case, with Connie (the head nurse) flagrantly disregarding Linda’s wishes, and Dr. Barton attempting to convince her not to worry about the maintenance of the estate, Linda finds herself intruding onto a locked world of adult secrets that she is nevertheless bent on uncovering. Leafing through her mother’s papers, she begins to piece together her mother’s unwholesome legacy of madness, conspiracy, and murder. But now the past seems to be reliving itself: residents of Montclare begin to die unexpectedly, she hears noises in the house, finds windows inexplicably opened, taps turned on, and shadowy figures on the horizon—a wonderful litany of paranoid devices with which horror films convey the sense that “there is evil in this house” or that “there’s somebody watching us.” Is Linda imagining these dangers? Are Connie and Dr. Barton (illicit lovers, we discover) presiding over a secret murder house? Why do these events seem as though they are designed to make her lose her sanity?

Next of Kin eventually pulls the rug out from under these psychological contortions in a breathless third act that makes good on its prior atmospherics. It is to its credit, too, that this transition doesn’t feel like an arbitrary twist, but - in its eruption of violence - reveals a series of structural patterns that tie the film together. The most evident of these motifs is presented in the first shot of the film: a slow-motion image of a scarred and blood-stained Linda, looking haggard and grim, and bowing her head in resignation on the rim of a pick-up truck—images whose context we will not understand until the final shot. While a pulsing synth dirge plays in the background, a woman’s voice-over reads: “To my daughter, Linda Mary Stevens, I leave my entire inheritance: all goods, chattels, and worldly possessions that comprise the estate of Montclare.” By superimposing images from the dark final sequence over the delivery of the narrative’s pretext, Williams evokes a sense of tragic inevitability about the film’s conclusion: as though there was no other kind of inheritance but that of loss. When we see a different version of this shot again at the end of the film, played frantically at normal speed, the effect is quite different, but here the opening note is one of resignation and melancholy. These are emotions of unusual density for a film of this kind, and especially to throw out in the opening frames. It is a daring gesture that raises the stakes for the rest of the film, while also providing the audience with a shock of recognition each time the story moves us closer to that initial image: when we see Linda scuff up her otherwise pristine face, when her hair becomes disarrayed, when she finds the keys to the truck, we can start to sense the narrative inching closer to the atmospheric swoon of that first shot.

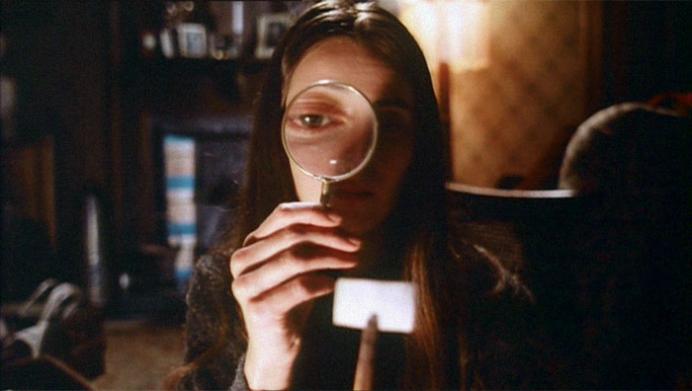

Throughout the film, too, the arch stylization of the cinematography (Williams was a DP before he was a director) invests the action with an aura of unnerving calm. From the ritualistic dread in the opening scene, to the elegant slide of the camera down from the ceiling to settle on Linda’s enlarged eye framed by a magnifying glass; from the camera’s slow dolly back from Linda’s reflection in the mirror, wearing a read shawl she will take off only seconds later; to the harsh diagonal along which the camera pulls back from Linda’s face as she searches down the hallway, or, later, being pulled towards the outsized gravity of an old man’s eye peaking from the crevice of an open door, the film is full of moments of delirious grace that play a dual role in its narrative strategy. On the one hand, these shots function like style in a modernist novel, helping to tie the film together in the absence of a plot by suggesting the strain of intention, order and composition, in a world where the characters’ motives are unclear. But they also seem to frame Next of Kin’s concern with surveillance and investigation. Constantly on edge in the suspicion that her actions are being watched, while also secretly digging into her mother’s past, Linda is the focal point of two different kinds of anxious looking. The camera’s measured choreography around her in moments of apparent respite and its insistent, often otherworldly, slow-motion shots in moments of anatomized terror all redouble the suggestion of a patient menace at work in the film without taking sides as to where this menace is originating. The world surrounding Linda, whose face is often centered amidst a changing background, is thus fringed with a perplexing agency whose origin won’t be made clear until the masks drop in the stunning final minutes, when Linda finally takes revenge (with a fateful, and bloody, screwdriver) on the eyes that have been watching her throughout the film. Then the cinematography jumps into overdrive, following Linda’s screaming exit from the house with a distended, impossibly aerial, slow-motion sequence that plays the scene relentlessly against the action, distorting her voice as well so that it becomes a haunting soundtrack to her escape.

But while Next of Kin excels in these sequences of ethereally haunting pyrotechnics, it is also successful in its mundane scenes, which crackle with unexpected details and frequently bizarre dialogue. Consider one early sequence set in a cemetery in which Linda and Barney - after an Edenic skinny-dipping interlude - continue their flirting before (presumably) paying a visit to the grave of Linda’s mother. I say “presumably” because, although we see that they are clearly strolling through grass that is surrounded by gravestones, and although we also see Linda talking about her mother while making a wreath of flowers, we never see the mother’s grave itself, or experience a moment of solemn acknowledgement. The film instead foregrounds Linda’s playfulness and youth. “Yuck. This water stinks,” she lets out as she empties a vase of flowers for her wreath, “I hate dead flowers.” As the scene unfolds, Williams establishes a relationship between Linda and her mother while also conveying the couple’s off-kilter sweetness in an exchange that, onscreen, feels incontestably romantic:

Linda

I suppose you think I’m like her?Barney

Yep.Linda

Unreliable?Barney

Mm-hm.Linda

Unpredictable?Barney

Uh huh.Linda

Crazy?Barney

Oh yeah. [He smiles, takes the wreath and sets it on his head like a crown]Linda

Good!

Against the backdrop of mother’s death, in the middle of a cemetery, the film becomes unaccountably charming and romantic. Indeed, the tone of the scene is remarkable for the complexity, and precariousness, of the levity it evokes while also signaling Linda’s need to repress any knowledge of the past. When Barney tries to catch her up on the town gossip from the time she was away, Linda refuses to listen, but does so giddily, protesting with a smile that she doesn’t want to hear any of it.

Barney

Not even that Tom’s got a new stud farm?Linda

No.Barney

Lucy Parker, the fat girl?Linda

God, no.Barney

Nun in New Guinea?Linda

Best place for her.Barney

Doreen Lawrence…Linda

No!Barney

[He mumbles something under the hand she places to stop his mouth]Linda

I don’t want to know!Barney

Wally Fleming [he coos in sing-song staccato] slipped off his bulldozer, under the tracks. And his head… popped like a watermelon! [And, on this, he laughs and throws the wreath forward like a Frisbee for Linda to catch]

Linda and Barney are playing hooky from the dread that will soon envelop them, but the film’s attention here is joyous as well as ironic, luxuriating in their playfulness while circumscribing it with a darker level of awareness that hides behind the dialogue in the setting.

The unnerving playfulness of this scene may also help to account for Linda’s larger role in the film. As a young woman inheriting not only her mother’s property but also the knife-blade of her extremely bad karma, Linda seems alternately to embrace her adult responsibilities and to flee from them. The latter option, the movie suggests, is the most sane, and we are shown evidence of Linda’s kinship with children throughout. The most prominent of these is Nico, the precocious son of Harry, the Elvis wannabe and local diner-owner. In an early scene, we see Nico entranced by Linda’s ability to make pyramids out of forks. “A test of nerves,” she calls it, in an apt description of what will befall her later on. Nico smiles and adds a final piece of cutlery. “Watch this,” he says, and blows on the structure, which doesn’t collapse. The glance they exchange tells us that Linda understands this youthful world and the special magic of life without consequence or change. Later in the film, covered in blood and on the run from familial violence, Linda again takes shelter in the company of Nico, who is playing a late-night game of pinball in the diner. Having barred the door and armed Nico with a shotgun, a traumatized Linda builds a massive pyramid out of sugar cubes and stares disconsolately into the distance. Nico, thinking that she might need some food, tries to coax her back to the world. “Like a coffee?” he asks to an unresponsive Linda, who leaves a long pause after each question. “Hamburger? Violet Crumble? Polly waffle? Kit Kat? Minties? Ice cream? Chik-o-roll? Pastie…?” In a scene of uncompromising tension and impending danger, it’s astonishing to see the film veer so sharply back into the innocent world of Nico’s sweet tooth. Balancing the horrified deadness of Linda’s face against the obliviousness of Nico, for whom life is only a series of detours in between snacks, Williams stages a thrillingly apocalyptic vision of childhood, not as a refuge from the adult world, but as the ideal place from which to do battle with it. This kind of tonal swerve is indicative of the film’s genius, and suggests a world in which the playfulness of youth is the only weapon left in a doomed fight against the madness of growing up.

Next of Kin is so refreshing a film that almost everyone who writes about it ends by musing why Tony Williams hasn’t made a feature since. (Next of Kin is only the second, and final, entry on his IMDb page.) Indeed, it is the kind of achievement that would serve as a welcome capstone to most careers, but from a director who was still relatively young, such a disappearing act is puzzling. From what I was able to discern in a bout of research, Williams has had a long career making advertisements in New Zealand in the wake of this film, but the absence of any feature-length follow-up leaves many questions. Perhaps renewed interest - Next of Kin features briefly in the wonderful recent documentary about Australian cult cinema, Not Quite Hollywood, in which Quentin Tarantino (among others) lavishes it with praise - will succeed in drawing Williams back into the driver’s seat? Or perhaps - as with Next of Kin, which ends with Linda and Nico on the open road, speeding away from cataclysmic destruction —Williams found that, after this, there was nowhere else to go.

More 31 Days of Horror IX

-

The Addiction

1995 -

Psycho III

1986 -

Wake in Fright

1971 -

Blacula

1972 -

Big Foot

1970 -

Trollhunter

2010 -

Invasion from Inner Earth

1974 -

In the Company of Men

1997 -

Happy Birthday to Me

1981 -

I Drink Your Blood

1970 -

The Legend of Boggy Creek

1972 -

Maximum Overdrive

1986 -

The Giant Spider Invasion

1975 -

Ganja & Hess

1973 -

Not of This Earth

1957 -

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death

1971 -

Next of Kin

1982 -

Def by Temptation

1990 -

Shriek of the Mutilated

1974 -

The Manster

1959 -

The Alpha Incident

1978 -

The Bride

1985 -

Planet of the Vampires

1965 -

The Hole

2009 -

Vampire in Brooklyn

1995 -

Sasquatch: the Legend of Bigfoot

1977 -

Mad Love

1935 -

The Demons of Ludlow

1983 -

Habit

1997 -

Elephant

1989 -

The Blair Witch Project

1999

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.