Reviews

Penelope Spheeris

USA, 1984

Credits

Review by Victoria Large

Posted on 13 September 2011

Source 35mm print

Categories American Punk

There’s a clip on Youtube of Suburbia director Penelope Spheeris appearing on the daytime chatfest The Stanley Siegel Show in 1981 alongside other guests. All of them are there to comment on the punk movement, and all of them interact fairly awkwardly with the program’s eponymous host, who doesn’t “get” punk, or at least doesn’t want to. Spheeris scowls through most of it (maybe because Siegel starts the segment by saying, “This woman actually produced and directed the film,” as if that were difficult to believe). She responds to Siegel’s pronouncement that her famed L.A. punk documentary The Decline of Western Civilization is “very depressing,” with, “I know, but y’know, what was I supposed to do? Make a real happy movie? The world’s not that happy anymore.”

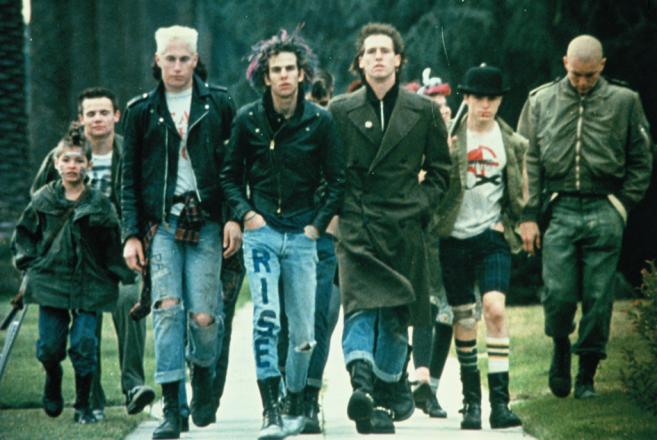

The quote could easily serve as a thesis statement for 1983’s Suburbia. In her narrative feature debut and a rare outing as both writer and director, Spheeris imagines a particularly savage Los Angeles complete with packs of wild, murderous dogs bounding through rundown neighborhoods. The film follows a gang of teenage punks who squat in an abandoned house and spend the bulk of their time running afoul of the locals. They call themselves The Rejected (abbreviating that to just “T.R.” for graffiti tagging purposes), but most of them have actually done the rejecting—escaping stifling suburban homes and unhappy family lives in favor of anything else, even if that turns out to be violence and squalor. Spheeris wants us to remember that her runaways are just kids, going so far as to include a scene of three punks gathering around a slightly older girl to hear her read fairy tales, and there are indeed moments of genuine camaraderie between the group that endear them to us, particularly when they take comfort in telling each other their stories or they playfully interact with Ethan, the grade-school-aged punk who wears his hair in a mohawk while he rides his big wheel.

Yet at the same time, Spheeris doesn’t let the kids completely off the hook for their behavior. She makes no bones about the fact they’re petty criminals prone to expressing stupid prejudices: a pair of them mocks a limping shopkeeper (this even though one of their friends has a prosthetic leg), and one boy leaves home specifically because his father is openly gay. (It must be said that the depiction of the gay father is a place where the movie indulges in some really disappointing and uncomfortable stereotyping.) Jack, one of the film’s lead characters, resents his stepfather because he’s a cop—and because he’s black. It is to Spheeris’ credit that Jack’s stepfather is depicted as the most sensible and compassionate character in the film - it reproaches Jack’s casually racist attitude, if only implicitly - but the writer-director also maintains a certain distance from her characters, almost as if she were creating another documentary.

Spheeris’ use of mostly non-professional actors and her prior experience as a punk documentarian lends Suburbia a certain degree of authenticity, and many viewers will twig to the moments in the film that echo the real-life details from The Decline of Western Civilization. (A poster for Decline can be spotted in the background of a scene in Suburbia.) The Rejected’s graffiti-covered lodgings recall the converted church where members of Black Flag are living in Decline, and when one of the young punks (played by The Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea) plays with a pet rat, it’s hard not to think of the Germs’ Darby Crash and his pet tarantula. Spheeris knows and sympathizes with punk culture, and that alone gains Suburbia crucial ground.

But the film does exist in a kind of heightened reality, summoning up the ghosts of sleazy juvenile delinquent flicks of decades past. This is a Roger Corman production, after all. Random acts of violence crop up to demonstrate willful brutishness that both the punks and some of their more extreme critics are capable of, but one senses that the violence is also there to give the target teen audience some bang for their B-movie buck. Something similar could be said for the bit early in the film where a female punk has her clothes torn completely off at a show and stands screaming and naked for what feels like ages before someone mercifully covers her with a jacket. In scenes like that one, it’s tough to say if Suburbia is trying to criticize the nastiness of what’s on screen or offer up a voyeuristic kick. It could be trying to do both, but the latter does do something to undercut the former.

Such contradictions make Suburbia a strange and interesting animal. A clear protagonist never quite emerges, but it also isn’t really the ensemble film that it might have been: this isn’t, say, a punk precursor to The Breakfast Club. The loosely structured story exhibits a punky disregard for the rules even as it prevents us from getting to know these kids more deeply. We lose an important character suddenly and struggle to understand why - which is probably the point - and the film ends abruptly with a tragedy so horrifying and needless that it stays with you for days. This is not, as Spheeris might have it, “a real happy movie.” It’s not a perfect one either, but there is power in it, and it stands as a suitably spiky entry into the punk movie canon.

More American Punk

-

Times Square

1980 -

D.O.A.: A Rite of Passage

1980 -

The Decline of Western Civilization

1981 -

The Return of the Living Dead

1985 -

Suburbia

1984 -

Border Radio

1987 -

Desperate Teenage Lovedolls

1984 -

The Blank Generation

1976

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.