Reviews

Sam Fuller

France, UK, 1990

Credits

Review by Cullen Gallagher

Posted on 03 December 2012

Source Echo Bridge Home Entertainment DVD

Categories Samuel Fuller: Deep Cuts

The Day of Reckoning is, without a doubt, Samuel Fuller’s weirdest movie. With echoes of D.W. Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat, Erich von Stroheim’s Greed, and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, The Day of Reckoning is at once an ecological horror movie, animal slasher flick, incestuous family drama, pastoral bloodbath, surreal psychological thriller, and allegorical fable about the dangers of industrialization. And it clocks in at just under fifty minutes. The movie may be short, but it has some of the most powerful and frightening images in any of Fuller’s work. Unfortunately, fans and critics alike have long overlooked it, relegating it to a minor footnote in the director’s long career. Violent, traumatic, and surging with political and philosophical ideals, The Day of Reckoning is a force to be reckoned with (forgive the bon mot).

The Day of Reckoning was made in 1990 as part of a British-French co-produced television series called Chillers. Each episode was based on source material by the great Patricia Highsmith, the same brilliantly twisted writer of Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley. The Day of Reckoning is a fable about nature reaping revenge on humanity. Set in the French countryside, it begins when Jean Arnaud takes a weekend off from school to visit his Uncle Andre’s chicken farm. Uncle Andre is intoxicated with his new system that manipulates chickens into laying more eggs by depriving them of natural light. Meanwhile, Aunt Helene is more intoxicated with fantasies of her nephew, and her daughter, Suzanne, is distraught over the death of her pet chicken. That night, Jean has a nightmare in which chickens not only talk, but they riot and take over the farm. John awakens only to discover his living nightmare is even more terrible than the one he dreamed.

The 1980s had been a rough period for Fuller. The decade got off to a promising start, with the production of The Big Red One, a WWII epic based on Fuller’s own experiences during the war. It was a film he tried to get off the ground for nearly three decades. After it was finished, producers re-edited the film without Fuller’s consent, cutting out over an hour’s worth of material. (In recent years, much of the material—but not all—has been restored). His next project, White Dog, was shelved by Paramount because of the NAACP’s unfounded criticisms of racism and their threats to lead a national boycott of the film. After that disappointment, Fuller relocated to Paris. Though always working on projects, only two came to fruition in that decade: the French-language Thieves After Dark, and an adaptation of David Goodis’ Street of No Return. Unbeknownst to the director, this would be his last theatrical feature film.

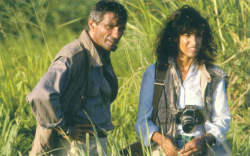

Fuller was 88 when he was invited to make The Day of Reckoning. It was not only a welcome professional opportunity, but it was also a family project. Fuller’s wife, Christa Lang Fuller, co-wrote the film with him and played a role, and their daughter, Samantha, also co-starred as Suzanne. Fuller describes the preproduction process in his memoir, A Third Face:

Christa cowrote a damn good script with me. For inspiration, we reread some of those formulaic detective tales from the forties like “The Case of the Lame Canary,” by Erle Stanley Gardner, and “Bats Fly at Dusk,” by A.A. Fair… The Day of Reckoning wouldn’t be green-lighted until Highsmith herself had approved our script. She did. When we met the grand dame in Paris during a stopover on her way home to Switzerland, she told us she loved our adaptation. The film was to be a twelve-day shoot on a strict budget with everything tightly synchronized.

The finished film is one of Fuller’s most bizarre and enjoyable. Age hadn’t dulled Fuller’s senses or capabilities in the least, and his visions of horror in The Day of Reckoning show a creative glee and excitement. Jean’s first step into the farm is a tensely evocative first-person tracking shot through the factory, uncanny in its quietude, and already anticipating the end of days for the factory. Jean’s nightmare, fueled by an atonal funk rendition of “Old MacDonald” clucked by a chorus of chickens, is a disturbing spectacle, unprecedented and without equal. And the climactic chicken coup is a sickening pageant of death, perversion, and feathers that evokes the carnage of D-Day (which Fuller experienced firsthand and recreated in his own film The Big Red One). The final scene is a nihilistic allegory, one of Fuller’s bleakest visions of modern times.

But The Day of Reckoning is more than just an acrid display of destruction. For all of his own accomplishments, Fuller was a humble man, frequently expressing gratitude for those who came before him, affection for his contemporaries, and support for younger generations. In The Day of Reckoning, Fuller pays tribute to three filmmaking legends. During their tour of the farm, Uncle Andre shows Jean the grain feed, a sight that immediately calls to mind a similar shot from D.W. Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat. The allusion not only foreshadows the impending death-by-grain scene (which originated in Griffith’s film), but also reinforces The Day of Reckoning’s anti-capitalist sympathies. Fuller’s grotesque close-ups of Andre’s raving face reminds of von Stroheim’s Greed, another film about the destructive and monstrous consequences of avarice. And, finally, there is the magnificently macabre vision of the chickens plucking out Jean’s eyeball during his nightmare, recalling similar shots from Hitchcock’s The Birds. Both films share a similar nightmare of the disastrous possible consequences of humankind’s inhumanity towards animals, and what might happen if the animals ever find a way to fight back.

Fuller, ever the storyteller, makes even the production process sound like a horror movie. As he recounts in A Third Face:

At the end of our movie, the wife locks the husband in the coop and releases the chickens. The animals go mad and peck the poor sonofabitch to death. To film that scene, hundreds of chickens were to be set loose in a closed courtyard. What we didn’t know was that the poor animals would be driven mad by their first contact with direct sunlight. The farm owner did. Since the animals were soon going to be slaughtered anyway, he was only too willing to have them die and charge the producers for damaged poultry, making double money on the deal. It was one of the saddest, most agonizing spectacles I’d ever witnessed. Blinded and terrified, the maniacal chicken scurried around until they finally dropped dead on the ground right in front of our crew. We hurriedly shot the scene before the chickens were nothing more than a sea of quivering feathers.

The Day of Reckoning is a rare and unusual treat from Samuel Fuller. Horror isn’t a typical genre for him, but he navigates the story expertly and with inspiration. Fueled by passionate and long-lasting images, as well as a strong (but not distracting) philosophical undercurrent, it’s a must-see for any fan of Fuller or Patricia Highsmith.

More Samuel Fuller: Deep Cuts

-

Verboten!

1959 -

Park Row

1952 -

Underworld U.S.A.

1961 -

The Day of Reckoning

1990 -

The Madonna and the Dragon

1990

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.