Reviews

Sam Fuller

France, 1990

Credits

Review by Cullen Gallagher

Posted on 04 December 2012

Source Bootleg DVD

Categories Samuel Fuller: Deep Cuts

It’s one of the most blistering, memorable openings in any Samuel Fuller film: First, a close-up of an elderly man’s face. The camera pans, revealing an M-16 pressed to his head. Holding the gun is a soldier. Standing nearby is a female photographer. “When I count three, take pictures,” the soldier orders. The photographer protests. The soldier counts to three, then executes the elderly man. “Bring me pictures,” the soldier commands. “I didn’t take it you crazy son of a bitch,” she screams. “You’re dead garbage,” he says. “Go fuck yourself,” she yells back. “Pray, bitch.” As the soldier readies to kill her, another photographer runs in, firing a revolver with his left hand while snapping a picture with his right. We’re hardly a minute into the movie, but one thing is for certain: this is classic Samuel Fuller terrain, a gutsy, in-your-face film.

The Madonna and the Dragon may be Samuel Fuller’s final feature film, but as this opening scene indicates, he was as furiously creative as ever. It’s an unforgettable introduction to a film that has the regrettable distinction of being the most critically and commercially neglected film in Samuel Fuller’s career. It was a made for television movie co-produced by the French companies Canal+, Flach Film and TF1, with the participation of the CNC (Centre National du Cinéma). To my knowledge, it has received no major theatrical or video distribution in the United States. The copy that I saw was a bootleg with forced Japanese subtitles and was several generations removed from its VHS master; tracking problems ran throughout, the left hand side of the screen was marked by some Martian-green lines, and the images themselves were so dulled that faces were barely discernible. But even the degradation of multi-generational video copying couldn’t quiet the screaming voice of its director. It may have been Fuller’s last feature as a director, but The Madonna and the Dragon is every bit as radical, ferocious, and outspoken as his first film, I Shot Jesse James.

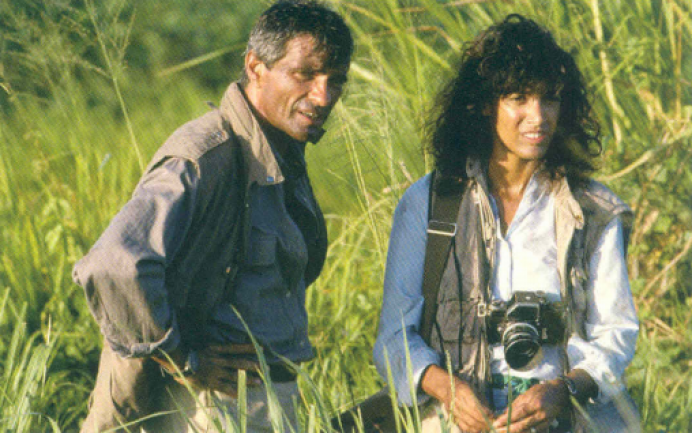

Set in the mid-1980s, Jennifer Beals stars as a photojournalist covering the People’s Revolution in the Philippines. The country is in the midst of a civil war between the reigning government under President Marcos and the guerilla army supporting Marcos’ rival, Cory Aquino. While photographing a junkyard, Beals witnesses one of Marcos’ soldiers execute an innocent civilian. The soldier is about to turn his gun on Beals when her ex-husband, also a photojournalist, comes to her rescue. The two of them team up with a juvenile informant—an aspiring musician who calls himself the King of Rockin’ Manila. Following a lead, the trio catches Marcos’ soldiers in the act of committing war crimes, and Beals’ ex-husband snaps a photograph of one of Marcos’ soldiers murdering innocent civilians. When word gets out about the picture, it becomes a hot commodity: the publishers want it on page one, Aquino wants it for propaganda purposes, and Marcos wants it squashed. It’s the photograph that could change the entire climate of the war, and no one involved - not Beals, her ex-husband, or the King of Rockin’ Manila - can hide safely in the shadows for much longer.

Along with Park Row and Shock Corridor, The Madonna and the Dragon is Fuller’s third film about journalists. (Fuller also wrote several scripts about reporters that were filmed by other directors.) Though they weren’t intended as such, these three films can be seen as a loose trilogy, with each film representing not only a different aspect of the journalistic trade, but also representing contrasting perspectives of Fuller’s unique worldview. Park Row is the most idealistic and optimistic—enunciating Fuller’s firm belief in democracy, and the pursuit of truth. His reporters speak alternately in headlines and manifestos—they embody all of Fuller’s high ideals for the profession, his respect for the heritage of the trade, and the sanctity of the journalistic mission. Shock Corridor shows Fuller at his most outraged, frenzied, and cynical—in order to uncover a murderer, a reporter commits himself to an insane asylum and, in the process, becomes insane himself. It’s his ultimate, and most disparaging, observation on life in the modern world: society is ugly, psychotic, violent, and merciless—and to recognize its true face is to risk being pulled into its nasty orbit, never to escape.

The Madonna and the Dragon takes a different approach. Instead of focusing on reporters, Fuller’s protagonists are photographers—a harmonious blending of Fuller’s two most ardent professions, reporter and filmmaker. Unlike Park Row, The Madonna and the Dragon offers a more morally and ethical ambiguous view of the profession. Throughout, Beals is repeatedly forced to question her role as a recorder of history. At what level is she, as a photographer, responsible for the violence she captures? Soldiers perform for the camera—some merely mug or strike a pose, but others enact further violence, begging for their slaughter to be immortalized. Is it right that Beals makes a living off the suffering of the people, while the people continue to suffer? Fuller’s film anticipates many of the questions that Susan Sontag would later ask in her book, Regarding the Pain of Others, and it suggests that Fuller himself is questioning his position as a filmmaker vis-à-vis the world he films. Going back to his first film, I Shot Jesse James, Fuller has been questioning history and deconstructing mythology. Here, in his last feature film as a director, he is still finding new ways to dispute official records and debate the role of cinema as an historical and narrative medium.

When we watch a Samuel Fuller film, we often think of him as the star, even though he never plays the protagonists (though he occasionally takes a supporting role, such as the editor in The Madonna and the Dragon). His personality and voice comes through the dialog, his ideas and philosophy is expressed visually through the shots, and his life experiences have given inspiration to the narratives. All too often, however, I think we over look the great roles he has given to his actors. In particularly, his female characters are remarkable for their independence, strength, professional achievement, and daring morality, often at odds with the standards of the times. Think of Charity Hackett, the strong-willed, enterprising, and unscrupulous editor of The Star in Park Row (played by Mary Welch). She’s ruthless yet entirely sympathetic. And while she may be the story’s antagonist, she’s never an outright villain. Not only a powerful business force, she’s also a vibrant sexual being, as well. There aren’t many other female roles this dynamic or daring in early 1950s Hollywood, when much of the industry was still limp and gutless out of fear of McCarthy. Then there is Angie Dickinson in China Gate. She introduces a female character into a predominantly male genre—the war film. Whereas most Hollywood war films of this time would portray women as soldiers’ wives or girlfriends back on the home front, while the men are off fighting, Fuller takes a different approach. Set in Indo-China, Dickinson is a central member of the squad, leading them through the jungle to their destination. Fuller, ever a believer in democracy and gender and racial equality, ensures that Dickinson is an equal player in the group and their mission. Then there’s Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss, the prostitute who reforms herself and moves on but is stuck in a world that can’t see beyond moral labels. She takes control of her life and her body, but society’s mind is still stuck in the puritanical gutter that views sex as a sin and free-willed women as a threat that must be contained and destroyed. Barbara Stanwyck’s dictatorial rancher in Forty Guns is likewise a powerful threat to conventional morality, gender constraints, and even genre conventions—Fuller lets Stanwyck break all the molds in that one! And here, in The Madonna and the Dragon, Jennifer Beals continues in this tradition of morally nuanced, independent minded, professional women out there in the front lines of the modern world, fighting and creating and carving out a role in history for themselves.

Fuller’s contributions to cinema were many. Memorable stories, dynamic characters, unforgettable shots, and an undying artistic spirit that still inspires, motivates, and urges young filmmakers today to pick up the camera and create their own cinema. It’s a shame that The Madonna and the Dragon was Fuller’s last film—not because it was an unworthy film to go out on, but because it showed that Fuller was still full of fresh ideas and cinematic vigor. In a way, however, it is a testament to his power as an artist. From first film to last, Fuller’s body of work is astonishing. While the circumstance surrounding his films fluctuated, the vibrancy, ambition, and achievement of his work never diminished.

More Samuel Fuller: Deep Cuts

-

Verboten!

1959 -

Park Row

1952 -

Underworld U.S.A.

1961 -

The Day of Reckoning

1990 -

The Madonna and the Dragon

1990

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.