Reviews

Peter Fonda

USA, 1971

Credits

Review by Jared Eisenstat

Posted on 09 April 2013

Source Sundance Channel Home Entertainment DVD

Categories Acid Westerns

Peter Fonda trades in his hog for a horse in the 1971 revisionist Western The Hired Hand, in which he plays the leading role and makes his directorial debut. Released two years after his star turn in Easy Rider, it’s also a sort of road-movie/buddy-flick. Cribbing from that earlier film’s playbook while shifting to the Western mode, it puts its own distinctive spin on the genre. Universal was banking on a clique of counter-culture phenoms to spawn a series of cash cows in the Easy Rider mold, and funded a slate of low-budget pictures by these young filmmakers, of which The Hired Hand was one. Bottom-line hungry, Universal was disappointed by the film’s dismal box office results, and so it languished in their vaults. Thirty years later, this little genre gem was dug out of the archives and restored by its original editor, Frank Mazzola.

It’s the late 1800s, and Harry Collings (Fonda) aimlessly roams the Southwest. He married young and got the seven-year itch five years early, leaving a jilted wife and infant daughter behind at their homestead while he went to chase the lure of the open country. A lost soul, without purpose or meaning, he’s been wandering the untamed West in the seven years since, “finding himself” in anachronistic 1970s style. Fonda is pensive and earnest here, with a quiet intensity that speaks from his soulful blue eyes. Joining him on his ramble across the American outback are Arch Harris (Warren Oates) and Dan Griffen (Robert Pratt). Arch, older and wiser, has been riding with Harry since just about the beginning. As incarnated by Oates, the legendary supporting actor of grit and rasp, Arch is a thoughtful, dependable soul who’s always ready to flash a toothy smile and help a friend out. The boyish Dan is a rambunctious young buck, fresh-faced, naïve and hungry for life, with a hankering for the beaches and broads of California.

The Hired Hand announces its outsider status from the outset. It opens over the Rio Grande, and the first scene is drenched in outré stylization: stretched out by slow-motion, in high contrast, with dissolves, still frames, over-exposure, focus-shifting and bursting with prismatic light. These are lengthy shots, and superimpositions layer the same scene from different angles and distances. A lone banjo twangs out a tune, soon joined in counterpoint by a fiddle. Jubilant, Dan flaps about naked in the water while Harry stoically fishes, but they’re barely recognizable and seem more like abstract metaphoric figures. The contemplative register orients us to the deliberate pace of the film and the interior, existential mood that suffuses it. Although these artistic touches recur throughout, after this expressive beginning the movie settles into a more familiar visual and editing style, with an unobtrusive, naturalist look alternating with the frequent close-ups typical of films from the era.

The story proper begins with Harry, Arch and Dan eating and gabbing about their plans, relaxing and enjoying the freedom of the open country. How swiftly their calm shatters, though, when they find a dead young girl in the water, snagged on their fishing line as her corpse floated down the river. Shaken by the ill omen, they ride off and into a dusty old ramshackle excuse for a town, Del Norte. In a quiet moment at dusk, Harry and Arch share a whiskey in a visually striking scene cut with a curious editing technique: Arch and Harry are in silhouette in the foreground, and the sky above dissolves away, replaced by superimposed close-up shots of them in full color. It distracts and confuses, but also heightens the expressivity of the scene with a doubly intimate feel of the two men sharing a moment. There’s some arty period pretense at play here, but it’s also a refreshing bit of ingenuity and a sign of lively aesthetic experiment. Alas, the town of Del Norte is presided over by a gang of unsavory “We don’t take kindly to your type around here” thugs. Things can only go south, and before long a shot rings out. Dan stumbles into view half naked, and dies a gruesome death, bloody and crying for Ma. Harry and Arch, who watch as their young friend dies in their arms, know something’s fishy, and manage to exact revenge of a sort, before they flee into the dawn.

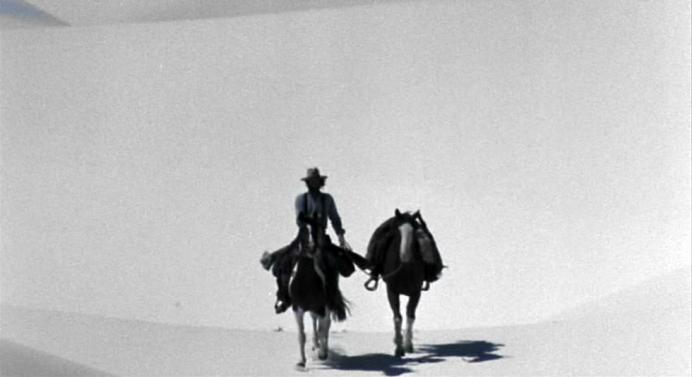

At last Harry has an actual destination: he’s heading home. His existential dalliance is over: after all he’s seen, he’s ready to re-embrace the life he left behind, settle back down and take responsibility. It’s a reverse road trip, an Odyssey of sorts as Harry makes his way back to his house, his wife and his child after long years away. Arch joins him for the long ride, and we get a sense of their easy camaraderie as they travel over varied landscapes of forest, mountain, white sands, plains, glens, and grasslands. Cinematographer Vilmos Zisgmond captures it all with simple naturalistic honesty. (The following year Szigmond shot another backcountry film with a catchy twang: the thriller Deliverance).

Finally arriving at the farm, Harry reunites with his estranged wife Hannah (Verna Bloom). Bloom presents a hardened, brittle Hannah who has clearly had it rough and carries deep wounds. She’s all spitfire as she bristles at Harry’s return, lashing out at him for what he’s done and refusing to take him back. She finally relents when Harry, contrite, offers to stay on as simply a hired hand helping out around the property. Arch, with nothing better to do, decides to stick around with his friend. Harry takes the exhausting manual labor as penance and throws himself into it, no complaints to his wife, whose spiky exterior slowly crumbles as she watches him work, but who keeps him at bay at night by confining him to the barn.

A chaste love triangle develops, with the characters bound in every direction. As things finally patch up between Harry and Hannah, Arch - loyal to the end - packs up and heads out, despite Harry’s pleas to stay. In a private moment, Hannah reveals her insecurities about Harry disloyal flight seven years ago and his teaming up with Arch: “He’s what you left me for… he’s what you went looking for.” As Harry pledges loyalty to his wife, it looks like they will finally be able to rebuild their life together. But soon after, history catches up to Harry, and he must make one last ride out to the wild.

The screenplay’s by Scotsman Alan Sharp, who also penned Rob Roy, and who died this past February. His dialogue is peppered with authentic Western lingo and there’s an appealing searching quality to the words. The flip side is that the lines can come off as blunt, functional or wooden, as when Arch asks Hannah: “Why don’t you have a dog?” and she answers, “Had one but it ran away. Never bothered to get another,” in a heavy-handed analogy to her husband. But there’s also a general quietness; this isn’t one of those Westerns where everybody packs into a crowded saloon for some good times, or a big group of townsfolk gather to mutter about their troubles. Many scenes pass without dialogue, filled instead with spare music. Bruce Langhorne, a major 60s session musician for the likes of Dylan, composed a minimalist, folksy score for the film. His simple, repetitive melodies have a wistful feel, and use of a sitar at times imparts a droning quality.

The film upturns many of the conventions of the Western. Death and violence are sapped of glory and redemption and doused in awkward tragedy. Unconventional social arrangements prevail (Harry is ten years Hannah’s junior), and the central hero has abandoned his wife and child to follow his own vague yearnings. Female sexuality is accepted even to the level of adultery, if her physical needs and right to pleasure aren’t satisfied.

It’s strange, though, that the relationship between Harry and Hannah lacks heat. He seems mostly motivated by a moral duty to her and a desire to occupy a recognized social position; the relationship is about him and his obligations, not about anything between him and Hannah. Hannah, for her part, didn’t even recognize Harry when he came back. He’s a hardworking, handsome, gentle man, but we’re never given real hints about what drew them together years ago, or what brings them back together here. And their daughter seems like an afterthought, a plot detail to raise the stakes without giving her any substantial active role.

On the commentary track of the 2003 Sundance DVD release, Fonda says that “Westerns are our way of exploring our own mythology.” The Hired Hand claims the Western hero as a counterculture icon, casting the classic outsider in a new aesthetic to fit the conditions of early 1970s America. He still prowls the untamed wild, but now he’s unshaven, with long hair and a bandana, prone to deep conversations and existential drift. He’s no longer trying to save society; he’s trying to save himself.

More Acid Westerns

-

Ride in the Whirlwind

1965 -

The Shooting

1966 -

El Topo

1970 -

The Hired Hand

1971 -

The Last Movie

1971 -

Greaser’s Palace

1972 -

Bad Company

1972 -

Ulzana’s Raid

1972 -

Jeremiah Johnson

1972 -

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid

1973 -

Kid Blue

1973 -

Dead Man

1995

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.