Cousin

Jules

Dominique Benicheti

France, 1972

by Leo Goldsmith

by Leo Goldsmith

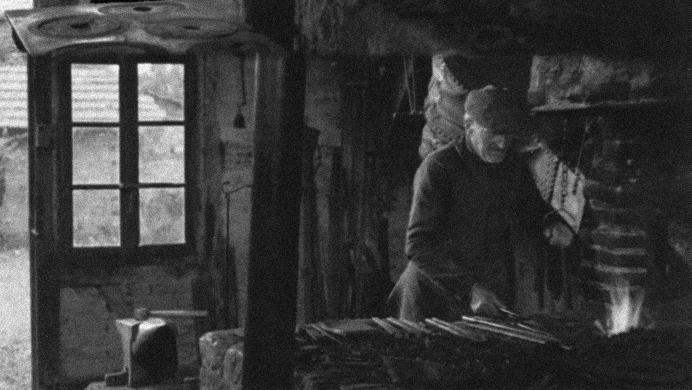

Cousin Jules gets up early each morning, puts on his wooden clogs, and walks across the yard to his iron forge to work on horseshoes, which he bangs together with hammer and tongs with the automatic ease and fluidity that come with many years of habit. His wife meanwhile meticulously denudes corn-cobs of their kernels and preps the lunch--a simple meal of boiled potatoes (with shades of Tarr’s _Turin Horse_). They eat and exchange maybe a dozen words between them. Jules returns to work, and soon his wife enters to prepare the afternoon coffee (with a hand-grinder and on a wood-burning stove). They sit, silently, and sip. Jules smokes a cigarette. Back to work.

The season changes. Jules is alone, shaving in a small mirror hung temporarily by the window. He sweeps the floor, makes his bed, feeds the chickens. The forge lies dormant as he sits at the table in his one-room cottage, cutting vegetables with care, then cramming them into a pot that will simmer for the remainder of the afternoon.

Director Dominique Benicheti was, some time later, quite a big deal in 3D entertainment, having pioneered immersive multimedia experiences at Parc du Futuroscope. This, his first film, is futuroscopic in its own way: achingly and extravagantly detailed, it’s a secret grandfather to those many recent rural-themed hybird documentaries, including Sweetgrass, Bovines, and Bestiaire. Benicheti’s film is no less immersive in CinemaScope than those films are in HD, summoning vanishing worlds with sensual immediacy and a twinge of regret.