Little Shop

of Horrors

Frank Oz

USA, 1986

by Rumsey Taylor

by Rumsey Taylor

Both an homage to 50s b-movie sci-fi and a musical in the tradition of the Hollywood of yore, Little Shop of Horrors is best described as an overfed parody of its influences. In lieu of cinematerpsichorean dance numbers or a straightforward extraterrestial fable there is a sadistic Elvis-inspired dentist and a treatise on the ethics of entrepreneurship. At the heart of it all is a carnivorous, alien plant bent on world domination. It ends, predictably, on a positive note, sustaining its otherwise tenuous association with its cinematic prototypes, with the underdog main character, Seymour, having electrocuted the monstrous plant to death, escaping with Audrey, his love interest, to the suburbs.

The film was released at the tail end of 1986, and was greeted by respectable holiday crowds before reaping considerably greater profits on home video. It is in any regard a commercial and critical success, but not the sort of enterprise that has invited critical reevaluation. It is Frank Oz’s most emphatic production (his third film following The Dark Crystal and The Muppets Take Manhattan), but nonetheless a film that seems inhibited by its peculiarity: too obscene a musical to be associated with the likes of Busby Berkeley, and yet too traditional to have been enamored with the sort of renown with which more contemporary ones have been received—Moulin Rouge!, Chicago, or Les Miserables. (This is not to mention the fact that it was released during the genre's least renowned and profitable era.) Of its dual Academy Award nominations Little Shop of Horrors boasts the rather appropriate triviality of spawning the first Oscar-nominated song with profane lyrics.

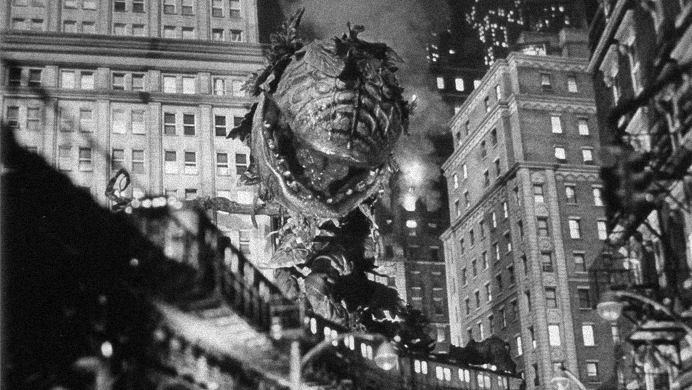

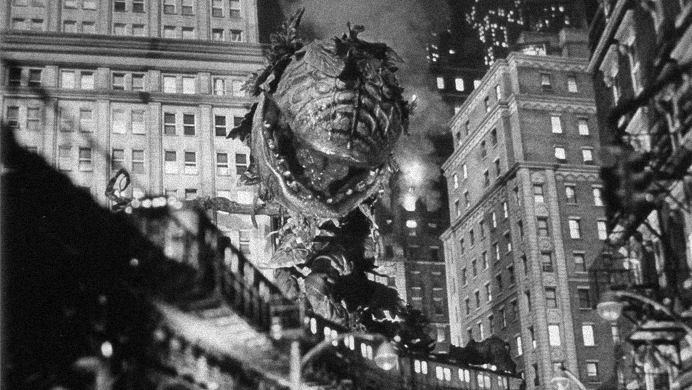

But as peculiar as it has come to be remembered, Little Shop of Horrors was originally conceived – and even produced – in even less traditional form. In the original version, the film concludes with both Audrey and Seymour devoured by the plant, whom Seymour has affectionately named Audrey II, which grows magnitudes, sprouts offspring, and proceeds to wreak havoc across New York City. It bursts out of the flower shop it had inhabited prior, careens down Broadway, tossing taxicabs out of its path like a child would a balloon, devours subway trains whole, and triumphantly ascends the Statue of Liberty. All the while, the alien flora is cackling maniacally—and all of this, do know, is set to song. At this moment the already idiosyncratic musical evolves, with essentially no predictability, into as bombastic and gargantuan a monster movie as Hollywood has produced. It is an astonishing sequence, so violent and radical in its departure from the preceding narrative, and a technical marvel, comprising miniature sets and composite photography. The final shot cements the sequence’s nihilistic conceit, with Audrey II’s enormous visage blasting out of the theater screen and the camera pulled fearsomely down her salivating, membranous throat.

The film was shown to test audiences in this form, and the results were reportedly disastrous. The death of the two leads was a coup so contrary to the audience’s expectations that when producer David Geffen suggested a reshoot Oz complied without resistance, delivering – after another round of production and a delay in the release – another cut. The original cut remained undistributed until the film’s release on DVD in 1998, in which it was included as a supplement and in the form of a workprint, with the additional material rendered in black and white. This version was quickly recalled, and the DVD became a prized piece of movie memorabilia found on eBay in its infancy.

The original cut of the film was restored in color and debuted at the New York Film Festival, and subsequently on Blu-Ray, in late 2012, some twenty-five years following its original release. Little Shop of Horrors is – irrespective of its two forms – a great film that features both a stellar performance from Rick Moranis and what is unequivocally some of the most sophisticated puppeteering in all of cinema; Audrey II, in her tantamount iteration, grows to over twelve feet tall, and was manipulated by upwards of twenty puppeteers and articulated alongside live actors. It is a wonderful spectacle at its most basic level, and one rendered all the more impressive in its original, more despairing and destructive form.