Reviews

Angustia

Bigas Luna

Spain, 1987

Credits

Review by Adam Balz

Posted on 26 October 2008

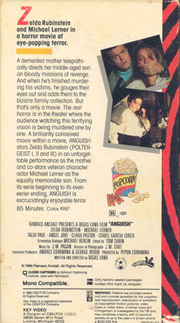

Source Key Video VHS

Categories 31 Days of Horror V

It is not so far-fetched to believe that movie box covers may well have been, and perhaps continue to be, designed with the sole purpose of misleading the unsuspecting horror film junkie. Keep your eyes open people. That is all.

—Tom Scalzo, ShockJuly

When I purchased a VHS copy of Bigas Luna’s Anguish for $1.11, I did so on the basis of nothing more than the film’s cover art: a black-and-white close-up of actress Zelda Rubinstein, apparently without any makeup, her face obscured behind a large, hypnotic, edge-to-edge spiral interrupted only by the film’s yellow title, white tagline, studio insignia, and larger banner in the bottom right corner offering a “WARNING!” to us, the viewers: “Contains scenes of powerful hypnosis, shocking crimes and unrelenting terror.”

A warning made with the best of intentions. The story of a middle-aged hospital intern named John who is slowly succumbing to an unspecified form of ocular degeneration, Anguish finds a truly nightmarish character in John’s mother, a shrill, hermitish old woman who controls her son’s every move through a mercifully unexplained psychic power. They share in delusions – that John is the city’s best optometrist, that everyone in the hospital looks upon him in either pure admiration or utter jealousy – while living together in a house populated by birds and slugs.

Their first victim is one of John’s patients, a woman who ridicules him in an earlier scene for being clumsy with her new contact lenses. John’s mother hears the woman’s derision through a conch she keeps in her living room: pressing it to her ear, she hears a torrent of criticism directed at her one and – we presume – only child. That night she dispatches her son to the woman’s opulent home under the guise of correcting “a terrible mistake” on the clinic’s part, and while she is fitted with new lenses – more comfortable, she admits – he cuts her throat, then methodically cuts out both of her eyes. Within minutes he does the same to her husband, making sure afterwards to wash all four amputated eyeballs in the couple’s lavish bathroom sink.

John and his mother, we soon discover, are collecting eyes – tens, maybe hundreds of different eyes – in jars of fluid. Their goal is to eventually correct John’s own condition, though this process remains unexplained. Instead, his mother feeds him a meal of milk and sliced bananas before hypnotizing him, presenting us with an undeniably surreal and unbelievably disturbing montage of John and his mother mingling like spirits, complete with hordes of slugs and their winding spiral shells. It is at this point, almost thirty minutes in, that the camera pulls back, delivering us into a darkened movie theatre. Blazoned across the screen is John’s psychedelic mind-scramble, and as the camera cuts to various members of the audience we discover this is The Mommy, a horror movie being shown in a downtown somewhere to a spattering of people.

Two of these theatergoers are Linda and Patty, both young women and close friends. Linda is older, more mature, and handling the movie with the distance and composure of a dedicated horror buff; Patty, meanwhile, is absolutely terrified. And no wonder: the hypnotism scene, as unbearably long as it is, gives way to the apparent climax of The Mommy, in which John buys a ticket to a midday screening of The Lost World and begins to slowly, madly, kill those seated around him. Stabbing them through the backs of their chairs and severing their spines, he carefully removes their eyes and places each in a plastic baggie in his coat pocket.

What follows is masterful cinematic patchwork on the part of director Bigas Luna. Using the often misused practice of crosscutting, Luna begins overlapping both his frame film and The Mommy, cutting between images of John seeking out his next victim like a wild predator and Patty scouring the theatre, trembling and on the brink of mental collapse. John makes a movement through the theatre; Patty’s eyes scour the empty seats and walkways as though her eyes might find him. Linda tells her she can leave but Patty never does, choosing instead to stay with her friend and endure a film that, from our own perspective, has almost little purpose outside of pure, unadulterated, unsettling gore.

Unbeknownst to Linda and Patty, as well as everyone else in the theatre, there is a killer among them, watching The Mommy with passionate delusion. He identifies with John, mimicking his every action step by step as the film progresses, even correcting mistakes he seems to see in the fictitious man’s methods: when he kills the ticket-seller and concessioner, just as John does, he drags their bodies to the women’s bathroom rather than leaving them out for anyone to see. By the film’s end he will stand in front of the screen holding Patty as his hostage, crying out for his mother just as John does on the large screen behind him.

Which makes the cover of Anguish near perfect. Though not without its eerie aspects – for one, from afar, the solid red shape makes Rubinstein’s face appear to be printed in color, an illusion that disappears as you get closer – the cover is a complete and masterful embodiment of every major theme in Luna’s film: the mother’s domineering, sometimes Oedipal hold over her grown son; the idea that cinema can by hypnotizing, forcing us to commit acts of unspeakable violence; the diminished boundary between fantasy and reality.

But most important, at least for me, is its purposeful deception. Nowhere on either side of the cover, front or back, is there any hint that the film’s opening story is merely a fabrication—a movie within a movie. The perennial film buff, searching out a good horror movie, will enter Luna’s world with nary a clue as to the mind-bending shifts in focus and story. We are drawn in because of the cover, and the cover pulls a fast one—an incarnation, you could argue, of Saul Bass’ title design for Vertigo, only rendered on a frayed folding of cardboard around a plastic container. So we are drawn in – hypnotized, if you will – by the cover, the promise of horror, and once we’ve entered there’s really no turning back. We yield all power to the director and his film, becoming little more than a cage of birds.

More 31 Days of Horror V

-

The Dead Don’t Die

1975 -

The Brides Wore Blood

1972 -

Alligator

1980 -

Girl in Room 2A

1973 -

Zombie High

1987 -

Deathdream

1974 -

Link

1986 -

The Witching

1972 -

Nude for Satan

1974 -

Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare

1987 -

The Strangeness

1985 -

Brides of the Beast

1968 -

Seven Deaths in the Cat’s Eye

1973 -

The Curse of Bigfoot

1976 -

Dark Night of the Scarecrow

1981 -

Chopping Mall

1986 -

The Jar

1984 -

Killer Workout

1986 -

Moon in Scorpio

1987 -

The Legend of Hell House

1973 -

Cronos

1993 -

Black Christmas

1974 -

Grave of the Vampire

1974 -

Rana: The Legend of Shadow Lake

1975 -

Blood Voyage

1976 -

Fiend

1981 -

Anguish

1987 -

The Chilling

1989 -

Attack of the Beast Creatures

1985 -

Humanoids from the Deep

1980

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.