Reviews

Dead of Night

Bob Clark

USA, 1974

Credits

Review by Simon Augustine

Posted on 06 October 2008

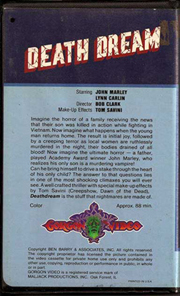

Source Gorgon Video VHS

Categories 31 Days of Horror V

Make sure to watch this late at night. If that is the likely prescription, and warning, usually supplied for horror movies, then with Deathdream, it is especially true. Like a lot of low-budget thrillers that played on the Late, Late Shows many of us watched as kids (in my case, after Tony “Mr. USA” Atlas did his thing for Channel 9’s Saturday Night Wrestling in the early ’80s), Deathdream makes up for in atmosphere and idiosyncrasy what it lacks in high-toned production values. This thing is creepy. The Vietnam-era American experience it portrays may serve as a time-capsule of a cultural moment gone by, but it is a skewed, claustrophobic, slightly dream-like version of that period, one that makes peering back into it all the more disorienting. And thus all the more appropriate for late-night viewing, a time when the mind is pleasantly winding down, lazy, off-guard, more susceptible to being drawn in and pleased by the subtleties of atmosphere; when, prepared to be dreaming soon in bed, it is most suggestible to the nuances embedded in the lulling pace and tone of a phantasmagoric ambience.

In fact, Deathdream reminded me immediately of one of the more memorable staples of that Late, Late Show: another soporific chiller called Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things (love those bizarro ’70s titles!), in which a flamboyant, hippie Svengali leads a troupe of actors to a remote graveyard to enact odd rituals. Children was written by a young auteur named Alan Ormsby, and directed by Bob Clark (who went on to make the semi-classics Porky’s and A Christmas Story). Sure enough, to my delight, I learned in the opening credits that Deathdream was made by the same writer-director team (and stars Ormsby’s then wife, Anya, as the sister of the Vietnam vet).

If Deathdream’s chilling effect relies on the director’s skillful effort to exceed the limitations of his budget, it stems just as much from his failure to do so. That’s what makes these ’70s B movies such a unique treasure: the creep factor lies in a fortunate combination of a few cleverly executed ideas with a general shoddiness and miniaturization of scale, rendering the dread a little bit off-kilter, a bit stranger. As with many of the best B-grade horror movies (Cronenberg’s They Came From Within, Romero’s Martin, and especially the classic Phantasm come to mind), the scenarios here are crafted in such as way as to create a kind of insularity, an eerie emptiness that feels as if no one else exists in town - and maybe the world - except the characters caught up in this particular nightmare.

At the onset of Deathdream an average suburban family waits for word from their son, Andy, who is fighting in Vietnam. Instead, the “moment every parent fears” happens: two military men, with glum faces, show up at the door bearing bad news. The family is devastated, especially Andy’s mother, who refuses to believe what she hears. But their sorrow is soon dispelled on a night following: hearing someone in the house, Andy’s father (John Marlow, he played the movie-producer who found a horse’s head in his bed in The Godfather) goes downstairs with a gun. Instead of a burglar, he finds his son, standing stoically in the hall. The family rejoices and embraces Andy, dismissing the prior news as a mistake. It becomes immediately apparent, however (to the audience at least), that all is not right with Andy’s demeanor; he is extremely removed and sullen, and as time goes on, he sometimes verges on being catatonic, or else is aggressive and moody. The movie isn’t as interested in the mystery of Andy’s return - to which the supernatural answer is pretty clear from the outset - as it is in focusing upon the dynamics and effects of playing out the ideas behind that mystery - including connotations to the real-life experiences of any soldier’s homecoming.

And though the allegory at play here does not ask the audience to do much detective work, it is nonetheless consistently unnerving and effective, because it is so conceptually rich for mining. Deathdream is a notch above the usual B horror movie fare for this very reason: eventually Andy’s condition deteriorates into a frightening spectre, and as his father grows to suspect he is committing murders in town, he is indeed revealed to be a homicidal corpse in the guise of the living. Some nifty and fun scenes are unleashed as the “secret” comes out, especially during a double-date at the drive-in when Andy’s old flame gets a nasty shock. But the real allure here lies in exploring, through Andy’s impossible homecoming, the ways in which a surviving, returning real-life soldier may actually leave his “life” on the battlefield; or, enduring the numbing impact of war, and the drain on one’s soul, how he may struggle with an existence as a psychological member of the “living dead” once back home. In the era before Post Traumatic Stress Disorder became a household name, watching the expression of the illness’s zombie-like grip in the form of a literal ghost story is a worthwhile exercise for a genre not known for its allegorical depth. The film aptly reflects the painfully remembered era when vets were excoriated and rejected for their service.

This is not to say that Deathdream wears its implications on its sleeve; there is nothing pretentious in its grim pacing, and Andy’s presence always retains the eerie kick of dependable urban legends like the famous “Vanishing Hitchhiker” or “The Hook.” When the film does get slightly ambitious, the attempt is always grounded in the usual, visceral aspirations of a good horror yarn: in one particularly well-done sequence, Andy follows the family doctor to his house and stalks him from the shadows. Once Andy emerges, he demands an exam, and then attacks the doctor with a syringe from his own medical bag, stabbing him over and over. Presciently symbolic, Andy insists that his victim “owes him something” - namely death, in return for his sacrifice as a veteran. Then, for a reason not explained, he drains the doctor’s blood with the syringe and shoots himself up, bringing alive not only vampiric imagery, but reminders of the terrible heroin epidemic among Vietnam vets.

On other occasions, the story becomes darkly humorous: in one scene, the neighborhood kids are invited to hang out with an obviously deranged Andy, and to their horror he strangles the family’s dog before their eyes. (Again, the disorienting effects of a B-movie budget kick-in, as amateurish reaction shots of the kid actors make the grisly act even more surreal.) Yet, the overall impression remains one of standard horror shadowed by a larger context, perhaps too relevant for comfort. The audience is left to their own devices in terms of how far they want to read into it: for instance, in Andy’s disturbing interactions with family and friends, does another allegory beckon - one about society’s unease around veterans, who are different because they have witnessed so much death, and perhaps carry the stain of death on them like a virus? Or in a kind of reverse version of the cult horror film Jacob’s Ladder, is everything that happens after the news of Andy’s death actually a manifested dream based on the dashed hopes of his family, especially the mother who refuses to accept his death; i.e., a wish-fulfillment turned nightmare? (Some make similar claims about wish-fulfillment in the “happy ending” of Taxi Driver, another film about the consequences of a Vietnam vet’s return.) Is the tension and suspicion between Andy and his father, a veteran of WWII, a reflection of the resentment felt by Vietnam vets toward the Greatest Generation, who were treated so much better than them? In its own era, this film must have made for pretty intense viewing by virtue of simply sparking such questions. It is not completely surprising, then, that in the climax, when Andy’s mother rushes him to the cemetery so he can finally be buried, the film actually strikes a sad, moving note. A bona-fide ’70s gem, Deathdream moves beyond it own time and genre to take on a fresh resonance in our new era of war and return.

Information from VHS Sleeve

Year

[unknown]

Run Time

88 minutes

Director

Bob Clark

VHS Distributor

Gorgon Video

Relevant Cast

[none]

Relevant Crew

Tom Savini (Special Effects)

Tag Line

A Boy Went Away to War. Something UNSPEAKABLE came back!

Rating

[unknown]

Clamshell?

Yes

Quote

[none]

Masterpiece?

No

More 31 Days of Horror V

-

The Dead Don’t Die

1975 -

The Brides Wore Blood

1972 -

Alligator

1980 -

Girl in Room 2A

1973 -

Zombie High

1987 -

Deathdream

1974 -

Link

1986 -

The Witching

1972 -

Nude for Satan

1974 -

Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare

1987 -

The Strangeness

1985 -

Brides of the Beast

1968 -

Seven Deaths in the Cat’s Eye

1973 -

The Curse of Bigfoot

1976 -

Dark Night of the Scarecrow

1981 -

Chopping Mall

1986 -

The Jar

1984 -

Killer Workout

1986 -

Moon in Scorpio

1987 -

The Legend of Hell House

1973 -

Cronos

1993 -

Black Christmas

1974 -

Grave of the Vampire

1974 -

Rana: The Legend of Shadow Lake

1975 -

Blood Voyage

1976 -

Fiend

1981 -

Anguish

1987 -

The Chilling

1989 -

Attack of the Beast Creatures

1985 -

Humanoids from the Deep

1980

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.