Reviews

Joe Johnston

USA, 1989

Credits

Review by Jonathan Foltz

Posted on 07 May 2012

Source Amazon Instant Video

Categories Favorites: Transformations

“Children,” Walter Benjamin once observed, “produce their own small world of things within the greater one.” In the microcosm of youthful feeling, the most everyday objects lose their proportion, bending under the weight of fantasy. This is why, Benjamin suggests, children are particularly drawn to objects that have fallen into disuse, “the detritus generated by building, gardening, housework, tailoring, or carpentry. In waste products they recognize the face that the world of things turns directly and solely to them.” The child recognizes its powerlessness in the small, the fragmentary and the broken, transforming the cast-off details of everyday life into the raw material for a parallel world of enlarged destiny.

For Benjamin, this is an utopian idea meant to show the corrosiveness of childlike desire that repurposes the world it finds, creating new forms of relation amid the dejected objects of culture—but that doesn’t mean that it can’t be exploited. In Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, Disney’s 1989 franchise-spawning money-maker, the mutability of childhood perception has been made the pretext for the safest of adventures. The film follows two siblings, Amy and Nick Szalinski, who - along with troubled neighbor boys, Ron and “Little Russ” Thompson - have been accidentally shrunk by the blast of their father’s “electromagnetic shrinking machine,” and are impelled to find their way home in the new-found jungle of their backyard. But while offering the appearance of a journey into the alien and forgotten life of the small - as in the wonderfully wordless nature documentary, Microcosmos - Honey, I Shrunk the Kids is, at least at the level of its plot, a more or less straightforward celebration of maturity, responsibility and family values. Amy and “Little Russ” become the playtime parents of an ad hoc nuclear family in the wilderness of the lawn, and return home to find their own previously fighting parents happily reconciled, leaving them all to enjoy the adolescent hell that suburbia has lying in wait for them after the credits roll.

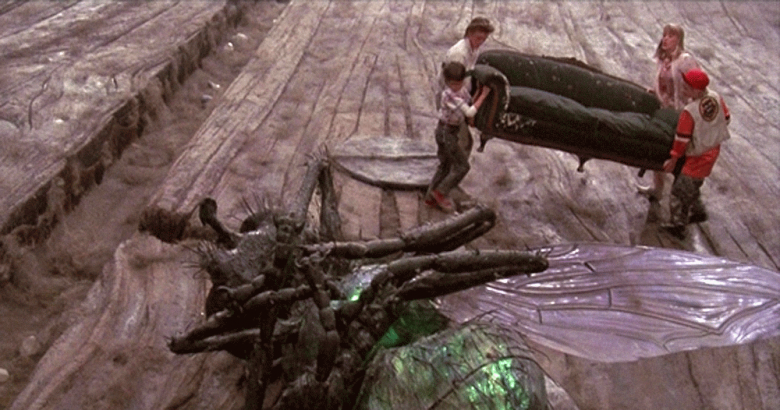

Probably, though, this reproduced domesticity is mainly there as a moral safety net. The real pleasure of the film exists in those details that fall to the side of what happens, in the rubberized, gleeful tactility of the film’s visual effects: the diseased pallor of the cow-sized dead fly floating in a “river” of potential dog urine, the sticky, hairy mouth of a friendly ant, the otherworldly texture of an enlarged Oreo cookie’s cream filling. These are the images of hypnotic matter that the film’s bizarre conceit is designed to unlock. Underneath the film’s oedipal veneer, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids revels in a phantasmagoria of dirt that is also the sign of a residual antipathy towards the vision of the family unit it seems destined to consecrate.

In many ways reminiscent of the subversive use of scale in Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids presents itself as an absurdist hymn to the distorted nonsense world of childhood. And yet it is remarkable to consider just how much of its actual narrative is spent chronicling the actions of the protagonist’s parents. From the Thompsons’ doomed attempts to plan a wholesome fishing trip to Mrs. Szalinski selling a house, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids maintains a comic interest in the mundane activities of the grown-up world. Chief among the film’s adult figures, of course, is Wayne Szalinski, the absent-minded inventor and ineffectual father played by Rick Moranis. He spends all of his time in his special room in the attic tinkering endlessly with his revolutionary shrink ray, leading to the neglect of his wife and children. In fact, when the film opens it seems as though his wife is on the brink of leaving him altogether: “Mom and dad had a fight last night,” says Amy to her friend, “and mom spent the night at grandma’s.” This is a bad sign, but from the tone of Amy’s voice it is also a customary product of his scientific obsession. It’s not that Wayne is an abusive husband, but he leads a self-indulgent life of arrested development that has doomed his family to dysfunction. He leaves the house in disarray (much to his wife’s consternation), and constructs ridiculous gadgets (such as a solar-powered coffee-maker or remote-control lawn mower), while the main outcome of his experiments has been that his shrink ray causes apples to overheat and explode. “An interesting way of making applesauce,” he mutters, with his face covered with the warm, mushy splatter of fruit. In essence, Wayne isn’t a father at all, but an overgrown child who lives out his youthful fantasies to destructive effects. This makes him a comic figure of humiliated authority, but also a warning about the perils of irresponsibility, and the eventual need to assume the mantle of the adult.

It is not enough that his machine accidentally shrinks his children (and those of the neighbors), but he then inadvertently sweeps the kids up and throws them out with the trash. Like those horrific stories of teenage mothers leaving their children in garbage cans - but sanitized for Disney audiences - Wayne’s unwitting disposal of his kids reflects his unreadiness for fatherhood, but it also indicates an abject, oddly hostile vision of childhood. The protagonists of the film, that is, undertake a journey that is an easy, but ill-fitting, parallel for childhood and adolescent development: from their miniaturized stature in a womb of garbage to a restored bigness in the shelter of the house. Unsurprisingly, the trash can, and the wilderness of grass it opens onto, is a much more fun place to be—it is musty, dirty and dangerous, but also an accommodating space of play and desire. A layer of slime turns the (oddly furry) blades of grass into impromptu waterslides; a vast puddle of mud allows Amy and Russ to experiment with sex via a mouth-to-mouth resuscitation technique he learned “in French class.”

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids was never going to be “Garbage Pail Kids” (with its emphatically profane, Rabelaisian vision of youth that was reviled by parents but hotly coveted by children), but it does harbor a kindred, if muted, fascination with the grotesque. “We’re all the size of boogers,” Ron exclaims in a moment of excitement. “Blow it out your shorts!” his brother yells back at him a few minutes later. This is deliberately juvenile dialogue, with a calculated indecency meant to entrance third graders. In a similar fashion, the film’s visual landscape - with its blown-up textures of hair, slime and mud - is a celebration of fetid matter, a zone of organic superfluity that lends to childlike bad taste the glint of objectivity. In a film about the pressures of growing up, this tarnished but alluring world of surfaces is as close as the film comes to imagining the immutable: “mud is still mud, no matter how small you are.”

This space of the lawn is supposed to be off limits to the adults. Early in the film we see that Ron has camped out in his backyard, rigging the site with an elaborate booby-trapped system of fishing-lines tied to a cross-bow, which his father, of course, walks into and sets off. “I’m not a trespasser, I’m your father!” he yells indignantly. But in the logic of the film, all adults are trespassers on their children, either overbearing or neglectful. The “Big Russ” Thompson forces his kids to act like adults, making “Little Russ” lift weights so he can bulk up for the football team. “If he wants to feel big he should act big,” he says gruffly at one point. The Szalinski kids, on the other hand, are forced to take on the role of adults because their absent-minded father does none of the chores himself. The children’s collective entrance into the Lilliputian world of adventure thus plays a double role: it grants them all a debauched reprieve from parental attention, in which they can luxuriate in the tactile pleasures of nature, but it also allows them the independence to discover adulthood for themselves. The sounds of the outer world still reach them in the jungle, but they become reinterpreted as expressions of liberation. In one telling moment, the voice of Mrs. Szalinski is calling out to them in the distance: “It sounds like mom,” says Amy. But the noise begins to change register, leaving Nick to observe: “No, it sounds more like a swarm of… bees!” Which of course it has now become. This is how the film processes the demands of adulthood by putting them at bay. The pressures of the adult world are digested through the film’s visual imagination, and spat out the other end in a displaced miniature form.

This is the sense in which the deus ex machina of the plot - framed through scenes of transformation (from the large to the small and back again) - registers its unease with the linearity of growth and the family structure. There is no disguising that the film is about the necessity, and problems, of leaving childhood behind, but Honey, I Shrunk the Kids is actually quite ambivalent about the form of maturity which it presents as a happy ending. The scenes of shrinking and unshrinking themselves are not prolonged spectacles, like many adolescent werewolf transformations that cloak a knowledge of budding sexuality and the body’s distention. Instead, these transformations happen almost instantaneously, lending a magical unreality to their effects; still, the film opts to give thickness and visceral force to the sticky, magnified world of grass and insects that the children wander through, negotiating their maturity but also resisting it. It is the space in which the dejected material of the world becomes the fabric for a nest of dreams. The film, of course, ultimately leaves this space behind - ending firmly within the warmth and security of the home - but in doing so it only demonstrates by contrast the insipidness of the life these kids have grown to inherit.

More Favorites: Transformations

-

Altered States

1980 -

Alien: Resurrection

1997 -

In the Mouth of Madness

1994 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids

1989 -

The Toxic Avenger

1984 -

Teen Wolf

1985 -

Teen Wolf Too

1987 -

An American Werewolf in London

1981 -

The Curse of the Cat People

1944 -

Face/Off

1997 -

That Obscure Object of Desire

1977 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

From Beyond

1986 -

The Beast Within

1982 -

The Family Man

2000 -

Starman

1984

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.