Reviews

Rod Daniel

USA, 1985

Credits

Review by Evan Kindley

Posted on 09 May 2012

Source MGM DVD

Categories Favorites: Transformations

As a child in the mid-1980s, I felt a strong desire to turn into Michael J. Fox. There is video of me in a denim jacket dancing in my parents’ living room to “The Power of Love” from the Back to the Future soundtrack, occasionally grabbing on to the backs of chairs and couches and pretending I’m skateboarding behind them (as Marty McFly does behind passing cars in the credit sequence of that film). I had other idols, of course - Michael Jackson was one; there are also pictures of me, from around the same time, wearing a single spangled glove - but the Fox obsession was particularly powerful, perhaps because Michael J. Fox’s brand of cool seemed more realistically attainable. I was unlikely to come anywhere near Jackson’s charisma or accomplishment, but I might have better luck with a diminutive, snarky Canadian.

What was it about Fox? (I feel strange referring to him by his last name, but it’d be equally odd to call him “Michael”; he’s one of those celebrities - and people - that are only correctly described by their full name, in this case including initial. (“Michael Fox” sounds extremely bizarre as well.)) He was neither a great actor nor a great comedian; he was cute and appealing in a non-threatening way, but neither especially handsome nor especially cool. He modeled adolescence in a particular way that I responded to, as a pre-adolescent: I was six in 1985, his annis mirabilis, when both Back to the Future and Teen Wolf came out, and he was twenty-four, but he perfectly incarnated the kind of teenager I someday wanted to become. I became briefly interested in the various passions and pastimes assigned to his various characters: Marty McFly’s skateboarding and guitar playing; Scott Howard’s basketball; even Alex P. Keaton’s Young Republicanism (which seemed impossibly exotic to the scion of a liberal Upper West Side family). These relatively mundane traits interested me more, in a way, than the time travel, lycanthropy, or proximity to a hot sister you would have thought would be the take-away from those roles; again, I think I was responding to those interests I felt I could mimic.

In Teen Wolf, Michael J. Fox wants to turn into someone else. Where Marty McFly is, for the most part, serenely confident, Scott Howard is a nerdier, more anxiety-ridden type. He is terrible at basketball. He works at his father’s hardware store - I think this is meant to signify some kind of working-class identity, not otherwise in evidence - and lusts after the unattainable and high-waisted-jeaned Pamela, while neglecting the attentions of his crushed-out best friend Boof. (The dynamic anticipates that of John Hughes’ Some Kind of Wonderful, released two years later, exactly.) “I’m sick of being so average,” he complains.

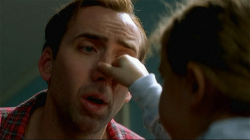

The solution to all of these problems, of course, is for Scott to turn into a werewolf, which he proceeds to do: a transformation that makes him popular, attractive to the ladies, and excellent at basketball while giving him almost no lupine characteristics. In contrast to its antecedent, 1957’s I Was A Teenage Werewolf, where the title character’s werewolfism is perceived as a problem, and implicitly likened to a psychiatric disorder, in Teen Wolf lycanthropy is pretty much a lifestyle choice: Scott seems to retain total control over when he turns (though he does “have to get kind of worked-up to be the wolf”—by anger, sexual excitement, or anxiety), and his transformation is cheered by his fellow students (especially when it means that they win more basketball games).

What does turning into a werewolf symbolize? Puberty, primarily - “I’m going through… changes,” Scott tells his coach - but a raft of other adolescent concerns as well: masturbation, homosexuality (“I’m not a fag. I’m a werewolf,” Scott tells his best friend Styles), drug use, race—or at least “blackness”: the wolf, with his basketball and breakdancing prowess, is Norman Mailer’s white hipster reincarnated for 80s teendom. In this way, it plays interestingly on Jackson’s 1982 long-form video for “Thriller,” directed by John Landis—of An American Werewolf in London fame. “The funk of 40,000 years” is, apparently, not solely an African-American inheritance.

Most of all, in Teen Wolf, lycanthropy stands for generational difference—or, rather, the lack thereof. Importantly, Scott’s father is also a werewolf, a fact he reveals for the first time after walking in on his son wolfing out in the bathroom. In their hairy regalia, father and son resemble nothing so much as hippies: their shared shagginess brings them together. Teen Wolf, like Hughes’s films, provides a 60s eye view of the 80s—it reads then-nascent youth culture through the prism of the Baby Boom’s own golden age, always looking for points of connection to an earlier, more familiar iteration of the counterculture. It’s of note that Teen Wolf is not even remotely scary - “Thriller” is way more terrifying - and that’s because it’s not meant to be. Becoming a hard-partying, sexually proamamiscuous werewolf is not a trauma but a rite of passage: proof that the rising generation’s cynical Alex P. Keatons are really just earnest counterculturalists like Mom and Dad.

Ultimately Teen Wolf is unable to maintain even the paltry degree of consistency it needs to keep this allegory going; it quickly devolves into a narrative about “being yourself,” which means not having to turn into a wolf in order to be popular (never mind that Dad had earlier insisted that “the werewolf is a part of you, but that doesn’t change what you have inside”). Boof loves Scott for who he really is, and he, the dummy, inevitably realizes it by the final freeze-frame. Here the drug metaphor is clearly most relevant, specifically steroids: “No wolf. Not now. Not ever. I wanna play… but I gotta be myself,” Scott explains to Coach—before playing the final game.

Needless to say, the movie doesn’t hold up very well, in large part because it misunderstands its star’s appeal. Leaving aside the fact that an unusually high percentage of the lead role is performed by a stunt double, I don’t think anyone really wanted to see Michael J. Fox transform into a werewolf. The change is not nearly as pleasing as seeing Marty McFly unintentionally seduce his own mother, or accidentally give Chuck Berry the idea for rock and roll (the white hipster strikes again!). Fox was so interesting to us, I think, because he didn’t seem to want to be like his (or our) parents: instead, he represented whatever was going to come next. In the mid-80s, he had a certain low-key futuristic vibe, also exploited in the Pepsi commercials made around this time: he was the taste of a new generation, a suburban, blow-dried Max Headroom. Robert Zemeckis played with this aura by placing Fox in the context of a pre-countercultural 50s idyll; Rod Daniel (Teen Wolf’s director, who would go on to helm the similarly furry K-9 and Beethoven’s 2nd) fucks it up by implying that what he really needs to be is a dutiful heir to a hirsute 60s tradition. But he’s gotta be himself.

More Favorites: Transformations

-

Altered States

1980 -

Alien: Resurrection

1997 -

In the Mouth of Madness

1994 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids

1989 -

The Toxic Avenger

1984 -

Teen Wolf

1985 -

Teen Wolf Too

1987 -

An American Werewolf in London

1981 -

The Curse of the Cat People

1944 -

Face/Off

1997 -

That Obscure Object of Desire

1977 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

From Beyond

1986 -

The Beast Within

1982 -

The Family Man

2000 -

Starman

1984

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.