Reviews

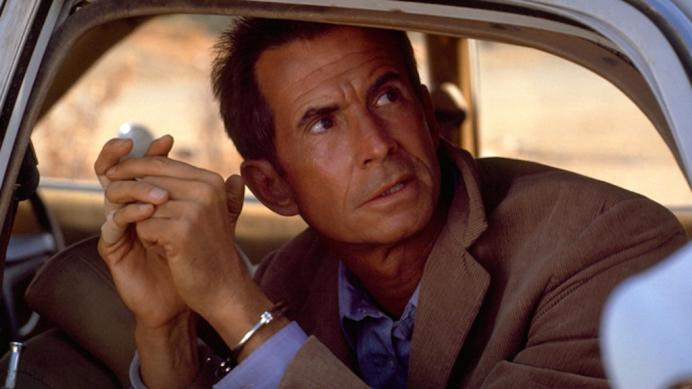

Anthony Perkins

USA, 1986

Credits

Review by Victoria Large

Posted on 02 October 2012

Source MCA Home Video VHS

Categories 31 Days of Horror IX

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 thriller Psycho is - sometimes admiringly, sometimes ruefully - regarded as the slasher subgenre’s Ur-text, the film that set off an endless wave of cinematic boogeymen terrorizing their victims with kitchen implements, axes, power tools, and the occasional custom-made glove. So it at least makes financial sense that Psycho itself was eventually seized upon as grist for the slasher-sequel mill, with the often entertaining, if somewhat jokey, Psycho II hitting screens in 1983. That film - scripted by Tom Holland of Fright Night and Child’s Play fame - has since amassed its own cult of fans (including Quentin Tarantino, who reportedly professes a provocative preference for it over Hitchcock’s vaunted original). But despite some genuine affection in B-movie and horror fan circles, Psycho II and the subsequent Psycho sequels are largely viewed as unnecessary and sort of depressing: commercial ventures that reduce Hitchcock’s exhilarating, rule-breaking horror film to a repeatable, bankable formula.

These criticisms are valid to a point - it’s certainly no accident that Psycho expanded into a franchise at the height of a mainstream horror boom - but I don’t plan on perpetuating them in this space. The truth is, I’m actually quite fond of Psycho II’s 1986 follow-up Psycho III, a watchable and likable picture that doesn’t deserve to be entirely written off as a cynical payday. Sure, Psycho III doesn’t match the bold elegance and innovation of Hitchcock, but it’s not reasonable to expect that it will. That it manages to have an appeal of its own is a worthy enough feat.

Though it superficially operates in the eighties slasher idiom, complete with a weird, gratuitous sex scene and a few murders that smack of Friday the 13th, this installment has surprising style and heart, and it’s infused with a nicely twisted sense of humor. (I love the gag involving some cartoon sounds emanating from a TV, and there’s a great little moment where our killer reaches out to straighten a crooked painting in the midst of stalking a possible victim.) Perhaps most crucially, Psycho III sees Anthony Perkins - who also directs this chapter with notable élan - once again playing the iconic Norman Bates. Much has been made of how the public’s desire to see Perkins as Norman belied the gifted actor’s versatility, but perhaps not enough has been said about his ability to find new and interesting ways to explore the character. At any rate, he’s this movie’s lifeblood.

Taking the convolutions of Psycho II into account, the third film picks up after Norman has been deemed “sane” and released from the institution where he spent over twenty years. Now he’s back in his original habitat, tending the struggling motel and imposing Gothic house where he committed his crimes. (This is twist is in itself a bit difficult to accept, but one must in order to get even a little enjoyment out of the Psycho sequels.) No need to rehash much more plot here, but know that as the film begins there is, once again, an elder woman’s preserved corpse lurking amid the decaying opulence of the Bates house, its presence signifying Norman’s own rage and guilt, his sordid and not-very-secret past.

What’s different this time is the arrival of a young woman named Maureen who nearly matches Norman in her mental fragility and capacity for self-torment. Maureen is a would-be nun on the brink of suicide in the film’s first scene. Not unlike Norman, she is so tortured by her own sexual desires that her behavior becomes dangerous. She ends up at the Bates Motel through a series of mishaps and coincidences, and the two lost souls quickly form a bond. That Maureen reminds Norman of his most famous victim, Marion Crane, right down to her initials and close-cropped blonde hair, makes the relationship more uneasy but perhaps also more important to the beleaguered Norman, who begins to see Maureen as his shot at redemption.

Hitchcock’s Psycho gave us an unforgettable glimpse at Norman’s dual nature: in one moment he is a nervy but pleasant young man made up of ticks and twitches, his hands fluttering like frightened birds; in the next he’s a maniacally grinning killer plunging a butcher knife into someone’s chest. Appropriately, Psycho III spotlights Norman’s disjunctive qualities to both humorous and poignant effect. As Roger Ebert writes in an insightful and surprisingly sympathetic three-star review from the time of Psycho III’s release, “Norman is not a mad-dog killer, a wholesale slasher like the amoral villains of the Dead Teenager Movies. He is at war with himself.” Perkins finds creative ways to illustrate this conflict throughout the film: I was particularly struck by the bit where Norman sits, pensive, while a man on television struggles against drowning, the TV actor’s panicked pleas for help seeming to mirror Norman’s own desperate thoughts.

Psycho III is especially good at teasing out Norman’s gentlest impulses, giving him ample opportunity to be awkward and caring and sweet, therefore making “Mother’s” inevitable explosions of violence that much more difficult to reconcile, and maybe that much more tragic. There’s a scene that finds Maureen and Norman taking to the dance floor at a local restaurant - he assures her that his mother taught him to dance - and seeing these powerfully damaged people enjoy a sliver of happiness produces a genuine ache. It’s comparable to the feeling of watching Carrie over again and futilely deciding that it would be nice if, this time, she could just enjoy being queen of her prom. We feel a similar pang later in Psycho III when Norman and Maureen end up in a clinch on one of the hotel beds. They decide to just hold each other but gasp ecstatically all the same; it’s the closest either of them has come to grown up, mutual intimacy, and, if only briefly, they are overcome with pleasure.

But this is a horror film, and we know as well as the characters do that the past can’t be rewritten. As Norman tells a prying reporter early on:

The past is never really past. It stays with me all the time. And no matter how hard I try, I-I can’t really escape. It’s always there, throbbing inside you. Coloring your perceptions of the world, sometimes controlling them.

Just as Norman could never resurrect his dead mother through taxidermy and role-playing, he can’t shake off the emotional burdens of his crimes by wooing a girl that reminds him of Marion Crane. Especially not when he apparently still has the not-infrequent urge to don a wig and stab people.

Yet while Psycho III could have turned Norman’s seemingly unbreakable cycle of madness into a rote cinematic exercise or a callous joke, it avoids these traps by employing some inventive touches and a measure of sensitivity toward its reluctant villain. It does occasionally jam an elbow in your ribs by referencing Hitchcock’s original (“I’ve seen it worse,” Norman assures Maureen after she notes that she left the bathroom in Cabin 1 a mess), but that’s pretty forgivable under the circumstances.

At its best, Perkins’ film recaptures the essence of one of cinema’s strangest and most fascinating characters, one that he happens to know terribly well. There’s a fleeting scene in Psycho III that’s tough to shake. In it, Norman stands in the pouring rain, cradling a victim’s lifeless body. Spontaneously, he bends and steals a kiss. It’s a wholly unexpected moment that speaks volumes about this character: a thumbnail sketch of a man who remains sick, frustrated, doomed—and yet oddly affecting, all the same.

More 31 Days of Horror IX

-

The Addiction

1995 -

Psycho III

1986 -

Wake in Fright

1971 -

Blacula

1972 -

Big Foot

1970 -

Trollhunter

2010 -

Invasion from Inner Earth

1974 -

In the Company of Men

1997 -

Happy Birthday to Me

1981 -

I Drink Your Blood

1970 -

The Legend of Boggy Creek

1972 -

Maximum Overdrive

1986 -

The Giant Spider Invasion

1975 -

Ganja & Hess

1973 -

Not of This Earth

1957 -

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death

1971 -

Next of Kin

1982 -

Def by Temptation

1990 -

Shriek of the Mutilated

1974 -

The Manster

1959 -

The Alpha Incident

1978 -

The Bride

1985 -

Planet of the Vampires

1965 -

The Hole

2009 -

Vampire in Brooklyn

1995 -

Sasquatch: the Legend of Bigfoot

1977 -

Mad Love

1935 -

The Demons of Ludlow

1983 -

Habit

1997 -

Elephant

1989 -

The Blair Witch Project

1999

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.