Reviews

Tom Holland

USA, 1988

Credits

Review by Victoria Large

Posted on 02 October 2011

Source MGM DVD

Categories 31 Days of Horror VIII

Although Chucky, the diminutive killer doll from Child’s Play and its many sequels, is occasionally mentioned in the same breath as those other eighties horror icons, Jason and Freddy, I scarcely need to point out that there are some key differences between Chucky and his taller brethren. Yet perhaps the most salient difference is this: while the Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street movies notoriously played on teenage fears, punishing underaged characters for engaging in drinking, drug use, and sex; Child’s Play harks back to the anxieties of small kids. It encourages its grown viewers to remember that one doll that looked terrifying in the wrong light, that one toy that seemed like it might have a sinister life of its own.

Child’s Play was not, of course, the first time that these fears were exploited in the context of horror. The film’s premise is a stone’s throw away from the well-worn trope of the creepy, sentient ventriloquist’s dummy, and it’s closer still to that of “Living Doll,” a 1963 episode of The Twilight Zone in which a talking doll begins issuing threats. But Child’s Play is notable in how well it exploits the idea of the evil doll - director Tom Holland builds some truly suspenseful sequences, particularly in the early going - and also because it places the evil doll in the distinctive context of the eighties slasher flick. More specifically, Child’s Play provides a potent mash-up of the slasher and another eighties juggernaut: the aggressively marketed children’s toy.

The eighties saw corporations taking on the so-called “Shortcake Strategy,” selling kids toys like Carebears, Popples, Cabbage Patch Dolls, and yes, figures of Strawberry Shortcake and her friends, via intense media saturation and endless tie-in merchandise. Parents descended on toy stores at Christmas en masse, battling each other for the hot toy of the season. Child’s Play couches some pointed, if underplayed, satire of this disconcerting segment of Reagan era consumer culture.

Andy, the young boy who ends up being the unfortunate owner of the murderous Chucky doll, is entranced by advertisements for “Good Guy” dolls on a TV. The ad seems to be airing during a “Good Guy”-based cartoon series, which Andy watches while wearing his “Good Guy”-inspired pajamas. The advertisement exhorts parents to buy the doll for their kids, because it’s perfect for birthdays or just “any old time,” and it reminds consumers to buy all of the “Good Guy” accessories too. In this way, the film gets in a well-aimed swipe at the toy companies that seek to monopolize kids’ imaginations and parents’ wallets, and it also offers an update on the childlike fear of dolls by supposing what would happen if the sought-after talking toy of the season started saying things that one wouldn’t want one’s child to hear.

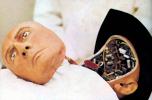

The Chucky doll itself, long rumored to have been inspired by Hasboro’s “My Buddy” dolls, is a perfectly realized bit of nightmare fuel, the kind of wide-eyed, round-cheeked sort of doll that is supposed to look friendly and innocuous but instead looks like it might bite. (Eventually, Chucky does bite Andy’s mother.) Perhaps it’s no accident that the doll’s designer David Kirschner, also one of the film’s producers, had a background in kids’ entertainment prior to Child’s Play. He’s even credited with creating the Strawberry Shortcake-like Rose Petal Place, an animated film with its own line of flower-inspired dolls, released four years before Child’s Play hit screens.

But Child’s Play - and, one ventures, much of its intended audience - is concerned less with media satire than with squeezing some solid thrills out of its enjoyably absurd premise. The film moves at a remarkably quick clip - sometimes falling back on convenient coincidence as a means of upping the pace - and it careens quickly through Chucky’s backstory. Charles Lee Ray, a murderer and voodoo practitioner, is gunned down by police in a Chicago toy store and uses his last moments to transfer his soul into the closest vessel he can find: a Good Guy doll. Andy’s widowed mom Karen, unable to cough up the Good Guy’s usual hundred-dollar price tag, then buys the possessed doll from a toothless street peddler at a steep discount. Mayhem swiftly ensues, with the usual slasher stuff, like shots from the killer’s POV, given a welcome tongue-in-cheek twist because one keeps remembering that these people are being menaced by a toy.

The performers wisely play the material mostly straight, trusting that part of the fun of the film will be the fact that it doesn’t wink at its audience. Catherine Hicks brings urgency and credibility to her role as a put-upon single mom in the middle of her worst nightmare, and Chris Sarandon lends just the right level of exasperation to his police detective character Mike Norris. Many of the film’s laughs come from Brad Dourif as the rude and wisecracking Chucky (heard but not seen after the film’s opening sequence) and character actor Tommy Swerdlow, hilariously nonchalant as Mike’s partner Jack.

Some of the best late eighties horror flicks sought to distinguish themselves from the hordes of low-budget shockers that flooded the market at the time by serving up their scares with good humor and a gimmick, and Child’s Play is happy to do both. Holland’s affection for the horror genre, so evident in his 1985 directorial debut Fright Night, shows in the verve that he brings to Child’s Play. The film has five sequels so far, and Chucky has become a familiar face, but to revisit this first film is to gasp anew at the weirdness of the plastic doll’s stiff features contorting with rage, and to smile again at the likable (and very eighties) lunacy that transpired when this year’s slasher boogeyman looked a lot like last year’s must-have toy.

More 31 Days of Horror VIII

-

Westworld

1973 -

Child’s Play

1988 -

Jacob’s Ladder

1990 -

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

1971 -

El Vampiro

1957 -

28 Weeks Later

2007 -

Piranha II: The Spawning

1981 -

The Others

2001 -

Quatermass and the Pit

1967 -

I Know Who Killed Me

2007 -

Bride of Re-Animator

1990 -

Alucarda

1978 -

Kakashi

2001 -

Seizure

1974 -

Night of the Living Dead

1968 -

Night of the Living Dead

1990 -

The Bat Whispers

1930 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Tintorera

1977 -

Paradise Lost

1996 -

The Cars that Ate Paris

1974 -

Ginger Snaps

2000 -

J.D.’s Revenge

1976 -

The Wicker Man

2006 -

Black Water

2007 -

Don’t Panic

1988 -

The Driller Killer

1979 -

Targets

1968 -

Mahal

1949 -

Event Horizon

1997

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.