Reviews

Gojira / King of the Monsters

Ishirō Honda

Japan, 1954

Credits

Review by Rumsey Taylor

Posted on 01 February 2013

Source The Criterion Collection BRD

Categories The Compleat Godzilla

Although the Godzilla franchise is at this point nearly six decades old, and has responded accordingly to capitalistic growth as any burgeoning, internationally exported franchise should, its central and eponymous creature has remained remarkably consistent in a physical sense. In this, the first Godzilla film, he is chiefly an antagonist, and the ensuing films will render him an ally, a father, and even something of a comedian. But in each of these roles his appearance remains invariable, as well as his single aural signature; it sounds like this.

The 1954 Godzilla is christened by this sound, which is preceded by the thunderous bellow of the monster’s footsteps. (This setup is repeated almost verbatim in some of the later films.) By the end of its second decade, the series would tend more towards camp than its opening chapter, but this scream remains loud and assertive, and each time it’s heard - particularly when Godzilla stands poised afore a crisp Tokyo horizon - the proceedings inherit an aspect of doom. The scream is in these cases a pronunciation of dominance, heard by all who lie insignificantly in the behemoth’s path.

This assertiveness, however, doesn’t precisely describe the characteristics of Godzilla in the franchise’s first entry. His attack on Tokyo, which ensues in the film’s second half, is interpretably a desperate retaliation. He had heretofore remained dormant at the bottom of the Pacific, having been rustled awake by a nuclear explosion that destroys his natural habitat. He proceeds outward, arbitrarily lashing back at whatever proximate force seems responsible for having destroyed his home.

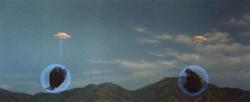

The scream is first heard at the film’s mid-point, when word of the nuclear explosion reaches Odo Island, just south off the Tokyo coast. The island natives know of Godzilla only in local myth (it is said that the island’s girls were sacrificed to bate his lethal appetite), although the probability of his resurrection is as amazing to them as it is to the Tokyo scientists that have travelled there; they all gape unbelievingly into one of his cavernous footsteps that strew the island’s perimeter. Shortly after, the beast appears, towering and unfathomably large, behind a mountain. He turns slowly toward us and gazes forward with uncertain resolve. It is here that we hear the scream for the first time. It is shrill, and perceptibly the sound of his anguish.

When Godzilla arrives in Tokyo, which first occurs at night, rendering his bizarre presence all the more mystified, he goes straight out of the ocean forward, seemingly into the heart of the city. Tokyo, home to over eight million people in the 1950s, is the only conceivable recipient of his wrath: a sprawling and sophisticated metropolis that the monster will seek to compromise, abetting the destruction of his own home with that of as many citizens as are within his reach. He screams at them to pronounce his anger, and breathes fire to subdue anything in his path. When he returns to the ocean, Tokyo’s once sharp horizon has been ably reduced burning rubble.

The principle human characters in Godzilla all pause between their thoughts, at first comprehending the magnitude of the problem at hand, and later to consider the consequences of killing him. Doing so requires an “oxygen bomb”—a capsule-like device deployed near Godzilla once he returns to his watery domain. It is a violent, uncompromising retaliation, and seemingly their only option. When they consider this, they do so knowingly, for fear that such a disruptive variable in an otherwise uncompromised natural domain will conceivably invite another behemoth visitor.

Godzilla is a film of paranoia and responsibility, foremost, and a monster movie in an expressly metaphorical sense. The later films will repurpose this film’s responsible human characters for redundant exercises in mayhem - and these films often have the additional task of justifying not only Godzilla’s return but that of other enormous monsters, as well - but they generally lack this film’s saga of cautionary environmental responsibility. Godzilla is destroyed at the end, but the end is wrought with no celebration, only a fear more pronounced than that of the beginning.

King of the Monsters

Godzilla proved successful in its native Japan in its original release, and its popularity spawned an American version, deemed King of the Monsters, two years later. This version of the film is tentpoled by the major plot points of Godzilla: the beast’s awakening and journey to Tokyo, as well as his subsequent death at the bottom of the ocean. But the proceedings are rewoven with new footage of an American journalist, portrayed by Raymond Burr, who happens to be traversing through Tokyo at the time of the attacks. Simply put, it’s the same film one generation removed from the source, narrated by an English-speaking surrogate to a similarly language-impeded audience.

It is in every regard a subordinate film, most especially in how it reduces the role of Takashi Shimura - an object of great pathos in Rashomon, Ikiru, Seven Samurai, and this - who portrays one of the Tokyo scientists. When Burr’s character, the ironically named Steve Martin, is thrust into the proceedings, he spends all of his time bewildered, and other, bilingual characters must translate things to him and, in effect, pronounce his emotions. The audience is treated similarly, and as a result the film is emotionally unambiguous and unnuanced. Steve Martin, what with his abject lack of comprehension of the Japanese language, effectively maintains the monster’s foreignness, and Godzilla, instead of being a more culturally transcendent cinematic creation, is kept in check as an exclusively Japanese one.

Nonetheless, King of the Monsters christens a very important aspect of all Godzilla movies, and that is how they were exported. Some of the films were repurposed into American or International versions, which is to say they were dubbed and reedited in some fashion, and this practice both dilutes their narratives and obfuscates their true drama. They sometimes became exploitatively campy as a result of this (two Godzilla films have been aped in MST3k versions). But the central cinematic conceit of these films has always been the scenes of destruction, and these suffer not from reversioning.

But with this, the Godzilla franchise is established on two fronts: one, a series of often responsible considerations of the ethics and repercussions of the atomic bomb, and two, a series of Japanese monster movies, with enough variety and bombast to entertain the world around for many decades, and enough technical prowess and innovation to declare a stamp in the landscape of cinema.

More The Compleat Godzilla

-

Godzilla

1954 -

Godzilla Raids Again

1955 -

King Kong vs. Godzilla

1962 -

Mothra vs. Godzilla

1964 -

Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster

1964 -

Invasion of Astro-Monster

1965 -

Ebirah, Horror of the Deep

1966 -

Son of Godzilla

1967 -

Destroy All Monsters!

1968 -

All Monsters Attack

1969 -

Godzilla Vs. Hedorah

1971 -

Godzilla vs. Gigan

1972 -

Godzilla vs. Megalon

1973 -

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla

1974 -

Terror of Mechagodzilla

1975 -

The Return of Godzilla

1984 -

Godzilla vs. Biollante

1989 -

Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah

1991 -

Godzilla vs. Mothra

1992 -

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla

1993 -

Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla

1994 -

Godzilla vs. Destoroyah

1995 -

Godzilla 2000

1999 -

Godzilla vs. Megaguirus

2000 -

Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack

2001 -

Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla

2002 -

Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S.

2003 -

Godzilla: Final Wars

2004

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.