Reviews

John Carpenter

USA, 1984

Credits

Review by Rumsey Taylor

Posted on 24 May 2012

Source Sony DVD

Categories Favorites: Transformations

John Carpenter’s Starman is titled possessively in the same manner as Carpenter’s other celebrated genre efforts, and its title, like most all the others, is rendered in the Albertus typeface during the credits. So from the get-go it’s as self-confident as John Carpenter films get, and pursuant to the director’s practiced interest in hopping across all genres and scoring these excursions in simple, infectious synthesizer scores, it is his first romance—a romance that begins in outer space.

It is at this point, in the film’s opening moments, that Starman’s anomaly within Carpenter’s body of work is proposed. The film is bookended by his more popular and profitable efforts on either end of the 1980s (only it and The Thing feature a score Carpenter did not compose). Like each of these films, it’s gained at least a decent amount of cult acclaim because of its inimitable heritage: Carpenter’s signature notwithstanding, it contains a rather bizarre performance by Jeff Bridges, for which the actor would receive the sole Oscar nomination that’s been given to any John Carpenter film; it also features Karen Allen, who seems to have internalized and repressed all the conflict she encountered three years prior in Raiders of the Lost Ark. The score is composed by Jack Nitzsche, whose work on a synthesizer is effectively indistinguishable from Carpenter’s. More generally, the film is a depiction of extraterrestrial xenophobia, a sub-genre that reached its commercial apex in the turnover between the late 1970s and early 1980s.

But absent is the subversion that’s come to describe Carpenter’s best films, the characters’ confident, knowing smirk when they say outrageous things and face supernatural conflicts. Carpenter’s archetypical films are comics with an R-rating that double as comedies with a sociopolitical bent. Starman is too tender and direct to warrant admission to this party, and as a John Carpenter film it is justifiably overlooked in favor of others that are fundamentally more characteristic. As firm and justifiable as this position within the hierarchy of his oeuvre may be, Starman is Carpenter’s most uncharacteristically unironic effort, and it concludes with what is in my mind the finest cinematic moment of his entire career.

The film opened in 1984, following Christine, The Thing, Escape from New York, and The Fog in consecutive years of the 1980s, a period in which his films would gradually return diminishing profits. This trend would continue for the remainder of the decade, but the last half finds a sort of return to form: Big Trouble in Little China, Prince of Darkness, They Live. Much of the novelty of Starman has to do with its status as an obvious departure from this group. Given a choice between five horror films, two science fiction ones, Big Trouble in Little China and this, a viewer unversed in the many pleasures of John Carpenter will certainly reach for the latter only after all the others have been consumed and enjoyed, many of them multiple times.

It is this underdog aspect of the film that encourages my own appreciation for it, for like all perceptibly minor efforts within a championed career it houses unforeseen joys. Starman yields many such pleasures, although its most curious aspect is how unexpectedly it satisfies Carpenter’s interests. It is a romance through and through, and it is often over-dramatized - due in no small part to Nitzsche’s score - in such pronounced fashion that you’re often watching in consternation and not reduced to tears, but Starman finds Carpenter in territory in which his practiced capability and preoccupations are clearly challenged. It displays the filmmaker at his most fumblingly, but its hallmarks are as strong and joyous as Carpenter’s others, even if they have not been ascribed with the same reverence as others in the same decade: the fight scene in They Live, The Thing’s dire conclusion, or Big Trouble in Little China’s entirety.

But these examples are all explicit, and for that matter Carpenter has always been interested in viscera over subtext. In this sense, Starman is - with a single notable exception in the transformation sequence - perhaps his most subdued film. Even the climax, in which a planet-like starship descends upon the Arizona desert to reclaim its missing occupant, fails to compete with the aural and visual spectacle of the nearly identical climaxes in E.T. or Close Encounters of the Third Kind—the ship itself is merely a reflective orb with no texture, and as the scene occurs in broad daylight it reflects only the surrounding desert. The focus of this climax, and that of the film in general, is not on the environment or the action within it as it is in other Carpenter films, but rather the characters’ internal experiences. Over the course of the film, these experiences gradually come to the fore, establishing two forlorn and incredibly unlikely lovers who, at the beginning, we know only for their innate sexual correspondence.

We’re introduced to the woman, Jenny, as she watches an old home movie of her and her husband. In it they are youthful and spry, but her observant face is transfixed and solemn, relaying immediately that the man in the movie is no longer with her. But most alarmingly, she looks no different than her filmic surrogate, only she no longer seems to possess the sort of cherubic delight that accompanies the assertion of true love that the home movie seems to depict.

The film’s title prefaces our foreknowledge of Jenny’s eventual reunion: she is visited by a star man - an extraterrestrial visitor with an abstract form who has crash-landed near her Wisconsin home - who enters her house after an evening of nostalgia and wine has contrived her slumber. It immediately comes upon the home movie, and naturally fixates on the more masculine of the pair it depicts. Within moments, and further enabled via scrapbook photos of the man as well as a lock of his hair, the alien being initiates a transformation into the man’s exact corporeal duplicate.

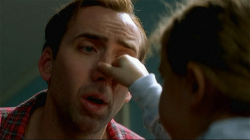

This scene is in isolation one of cinema’s great transformation sequences, and was enabled by two of the medium’s experts: Rick Baker and Stan Winston, between whom lie monsters of most every sort, cyborgs, dinosaurs, and eleven Academy Awards. The former was responsible for the werewolf transformation - the quintessential transformation sequence - in An American Werewolf in London three years prior; the one in Starman neatly evolves this sequence technologically: it begins with a closeup of a strand of hair, from which the being conceives a DNA model. It then conceives itself, starting with an infant form - wriggling on the floor and lathered in amniotic fluid - and grows, immediately and grotesquely, into a child and then an adult.

Jenny is awakened and comes upon the transformation before it’s complete, witnessing what is at first an unclaimed infant on her living room floor—an infant whose eyes shortly bulge out, ballasting a face that stretches quickly and seemingly painfully into a longer shape. This is already horrifying for both her and the audience, but this horror is irrelevant to what proceeds: within moments, the man we saw in the home movie footage is alive and standing, and is not perceptibly different from his deceased equivalent. Jenny’s face, heretofore frozen in the expression of solemn despair seen earlier, is conflicted. She faints, a victim of such violent miscomprehension that this revelation would hurt her even if it were only a nightmare.

The ensuing plot involves the star man’s desperate journey down to Arizona, where he’s to meet the ship that will enable his return to his home planet, a journey for which he forcibly enlists Jenny in aid. The film turns out much in the way one would expect, with the two reaching hurdle after hurdle and arriving at their destination at the exact last moment, but it’s at this point, early in the film, that its essential perversion is clearest: this alien could have taken any form in its goal to blend in to the human race, and has just happened to confront and exploit a poor woman’s grief for her dead husband.

Jenny is at first terrified of the star man, even though he’s as harmless as a child. His speech is primitive and absent of any melody, but he’s compellingly curious about everything, and his desire for knowledge and capacity for trust endear his statements with a child’s earnest curiosity. It is for this reason that Jenny is initially terrified of him. He looks exactly like her dead husband, but the mannerisms and personality are disturbingly amiss.

Jenny will grow increasingly more affectionate toward the star man—this is by some measure a plot contrivance, because she falls in love with him in less than three days, but it is, I think, an action that establishes her urgent necessity for love and, more significantly, closure. Her husband’s death isn’t illuminated, but you get the impression that it happened suddenly, and has depressed her so much that her initial terror and subsequent attraction to the star man are wholly justifiable responses. The star man becomes a form of entertainment for her, a replacement for the old home movie she’ll watch with an unending glass of wine, imperfect and yet more precise than any other corollary piece of ephemera of her marriage. It’s not long before Jenny sees him less as an alien visitor and more like a surrogate husband.

In this regard Starman has the same thematic concern as Vertigo, but these concerns are rendered more shallowly in Carpenter’s film. Nonetheless, I admire the focus on subtext over viscera, and even more so given that the subtext is facilitated by a genre filmmaker prone to indulgence. The transformation sequence is a glorious indulgence, and its relationship to the plot is somewhat specious considering how the film’s momentum is calibrated by the characters’ growing emotions and not the spectacles they encounter along the way.

In contrast to the lucidness of the transformation sequence, Starman’s finale is even more noteworthy for its restraint, not only within the context of this film. Carpenter had cemented his reputation for efficiency at this stage in his career, but at some point this efficiency became less characteristic than his directorial flourishes. Starman’s finale is preceded by over an hour of these embellishments: in addition to the transformation and spaceship sequence, there are explosions, car chases, and even a fleet of helicopters. These lead up to a moment of such unexpected and profound grace that I return to this film regularly: Jenny and the star man, narrowly beating the swarm of government officials who have endeavored to capture them, arrive at the Arizona crater that will serve as the star man’s rendezvous for his departure. Each knows they will part, and although the star man’s final sentiments are emotionally artificial and forced, Jenny’s are knowingly conclusive. This is for her the opportunity for closure her short marriage did not permit, and she sees the star man away not with tears but acceptance. The final shot remains irretrievably fixed on her face as the star man’s ship rises away, forever.

More Favorites: Transformations

-

Altered States

1980 -

Alien: Resurrection

1997 -

In the Mouth of Madness

1994 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids

1989 -

The Toxic Avenger

1984 -

Teen Wolf

1985 -

Teen Wolf Too

1987 -

An American Werewolf in London

1981 -

The Curse of the Cat People

1944 -

Face/Off

1997 -

That Obscure Object of Desire

1977 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

From Beyond

1986 -

The Beast Within

1982 -

The Family Man

2000 -

Starman

1984

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.