Reviews

François Truffaut

France/UK, 1966

Credits

Review by David Carter

Posted on 07 April 2010

Source Universal Studios Home Video DVD

Fahrenheit 451 sticks out like a sore thumb in Truffaut’s oeuvre. For the casual filmgoer — the one for whom terms like “auteur theory” and “French New Wave” are meaningless — it is possibly the only recognizable title in his body of work, and then only because of the Ray Bradbury novel, a favorite of high school curricula. Those more familiar with Truffaut recognize the film as a vast departure from his earlier work. Fahrenheit 451 represented a trio of firsts for the director: his first color film, his first large budget production and his first (and only) English-language picture. Fahrenheit 451’s difference from the rest of Truffaut’s films is but an infinitesimal aspect of why the film is so intriguing, however. It has its merits regardless of whether viewed independently or as a part of Truffaut’s larger body of work. Neither a line-for-line adaptation of the text nor a complete reimagining, the film is an excellent example of a filmic translation where both author and filmmaker have distinct voices that combine to make an extraordinary final product.

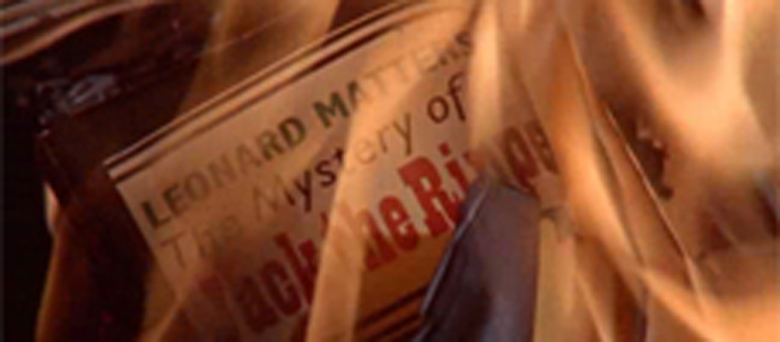

In an unspecified time in the future, “firemen” are a macabre inversion of what we typically expect. Rather than extinguishing fires, they are charged with locating and burning books in an effort to keep the general peace. Montag, a diligent fireman in line for a promotion, meets a young schoolteacher named Clarisse on his way home one afternoon. Clarisse questions Montag about the nature of his work and, more importantly, about the reasons behind book burning — questions Montag has never allowed himself to ask. Montag then breaks from his rigidly fixed routine by taking a copy of Dickens’ David Copperfield from a home while on a call. His curiosity about the taboo of books overtakes him and he finishes the book in a single sitting. Soon that curiosity becomes a hunger and Montag spends his nights reading everything he can find. His love of reading coincides with an increased zeal for book-burning from his superior officer, opening his eyes to the horrors of the world around him as he becomes the target of the “justice” he had formerly delivered.

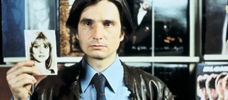

Fahrenheit 451 marked Truffaut’s second collaboration with Jules and Jim star Oskar Werner. Werner was not his first choice and their relationship soured during filming, at one point breaking down into what the director described as “a violent quarrel” over the actor’s repeated attempts to direct his own scenes. The source of the Truffaut/Werner conflict was the issue of whether or not Montag should be portrayed as a hero, a decision which Werner supported and Truffaut opposed. Truffaut’s refusal to allow Werner to be a typical movie hero gives the film a certain detachment more in line with Bradbury’s novel; Montag is not society’s savior but rather a fellow victim, only a small part of a story much larger than any one man.

This conflict between Truffaut and Werner informs not only the Montag character but the entire film. Werner plays Montag as a tortured soul, his face etched with absolute but directionless despair in every scene, perhaps as a result of the on-set tension or his reported contempt for his costars. In the early scene where Clarisse introduces herself to Montag on their train ride home, Werner looks so desperately uncomfortable that he seems capable of anything just to make the conversation end. His Montag is simmering beneath the surface throughout the film, making his later violent eruption more believable. Truffaut’s idea of the character may have been closer to the novel, but Werner’s portrayal of Montag as a caged animal is far more interesting, and the film is all the better for it.

As mentioned above, Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 deviates from Bradbury’s in several respects.1 The most immediately recognizable change involves the novel’s two female characters: Montag’s wife (called Linda in the film, Mildred in the novel) and Clarisse. Bradbury’s novel juxtaposed the wife and Clarisse, but Truffaut expanded on this idea further by making the latter a schoolteacher rather than a young student so that she and Linda would be of comparable ages. He also added a visual component to this contrast as well by having both roles played by Julie Christie. This casting choice underlines the fact that each character represents differing world views while also serving as an allusion to Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Unfortunately this juxtaposition remains at a superficial level, as Linda/Clarisse are little more than ciphers in the film, representative of Montag’s internal conflict between his desire to conform and his desire for the forbidden knowledge of books.

Truffaut also pared down some of the more fantastical elements of Bradbury’s story by eliminating technological advances such as the novel’s marauding robotic hounds. This heightens the realism of the film: viewers in the mid-sixties would have been able to regard the world of the filmic Fahrenheit 451 as not too far removed from their own, making the film’s message more resonant. By shrinking Linda’s full wall video monitor (“wall-screen”) down to something more akin to a television, the tension is heightened, making the dystopian future seem less distant and more likely to happen in their own lifetimes.

Truffaut’s visual contribution to Fahrenheit 451 is of great importance; working in color for the first time, he showed himself to be as capable in that medium as he was in black and white. Along with cinematographer and future director Nicolas Roeg, Truffaut gave the film a vibrant visual palette, but one that still showed the rigid constraints of the society depicted. The dramatic red of the firehouse and engine are contrasted by the rich, oppressive blacks of the firemen’s uniforms. The backgrounds of the claustrophobic interior scenes are completely taken up by walls, never windows or open space, and Truffaut visually emphasizes doors, openings, hiding places and other small compartments throughout the film to call attention to the increasing desperation of Montag’s situation — he is trapped. Very little time in the film is spent outside until Montag finally reaches freedom and the great outdoors.

Fahrenheit 451 remains intriguing and perhaps even more relevant now than at the time of its release, something that neither Bradbury nor Truffaut would have been able to foresee. What is American Idol but Linda’s beloved interactive wall-screen made real? We by no means have firemen burning books but the USA PATRIOT Act of October 2001 expanded the powers of the federal government to request and obtain library records for individuals. Bradbury stated in a 2007 article that the theme of Fahrenheit 451 was not censorship but rather how television takes away an interest in reading, and that criticism could certainly be extended to include newer technologies like the Internet.

Truffaut’s vision of the future has proven to be closer to reality than Bradbury’s, but both men have given us a glimpse of a world that is both wholly terrifying and possible. Of the two, Truffaut’s ending is greatly preferable that of the novel. The cinematic Fahrenheit 451 ends on a far happier note: a peaceful snowfall on the banks of a still lake. Though the almost total whiteness of the scene signifies the depths of winter, Truffaut’s image radiates with the idea that winter is always followed by a spring.

- Bradbury frequently expressed his approval for the changes that Truffaut made. His most direct approval came in his own review of the film published in the Los Angeles Times (November 20, 1966) where addresses the omissions from novel to screen: “Gone are the jets from my future sky, the mechanical hound from my street, the wall-to-wall TV from my parlor. By this seemingly rash elimination, Truffaut proves himself truly aware of the power of the film image… Once unleashed, he might well have turned a properly balanced drama into one more ride on the James Bond computerized carousel.” Bradbury’s indirect approval of Truffaut’s changes are evidenced by his decision to change the ending of his stage play version of Fahrenheit 451 to match the filmic version, rather than the novel. ↩

More Love on the Run: The Films of François Truffaut

-

Les Mistons

1957 -

Une histoire d’eau

1958 -

The 400 Blows

1959 -

Shoot the Piano Player

1960 -

Jules and Jim

1962 -

Antoine and Colette

1962 -

The Soft Skin

1964 -

Fahrenheit 451

1966 -

The Bride Wore Black

1968 -

Stolen Kisses

1968 -

Mississippi Mermaid

1969 -

The Wild Child

1970 -

Bed and Board

1970 -

Two English Girls

1971 -

Such A Gorgeous Kid Like Me

1972 -

Day for Night

1973 -

The Story of Adele H.

1975 -

Small Change

1976 -

The Man Who Loved Women

1977 -

The Green Room

1978 -

Love on the Run

1979 -

The Last Metro

1980 -

The Woman Next Door

1981 -

Confidentially Yours!

1983

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.