Reviews

L’amour en fuite

François Truffaut

France, 1979

Credits

Review by Victoria Large

Posted on 21 April 2010

Source Criterion Collection DVD

The evocative title of the final Antoine Doinel film, Love on the Run, does a fair job of summing up our story so far. Since we first met Antoine in The 400 Blows, he’s been looking for love. But he has also been running: away from school, from his parents, from the juvenile detention center, from the army — and, in the penultimate installment Bed and Board, he seems forever on the brink of running away from his young family. Though Bed and Board concludes on a note of arch optimism, suggesting that Antoine and Christine are settling into life as the kind of married couple who are perpetually exasperated with one another but nevertheless inseparable, Love on the Run finds the pair finalizing their divorce. (In a twist that’s hard to write off as coincidence, Antoine and Christine’s young son Alphonse is sent off to camp early in the film, a strategy that Antoine’s negligent parents favor in The 400 Blows.) Antoine has a new lover, Sabine, but he can’t commit to her: she wants him to move in with her; he won’t even keep a razor at her place. As an audience, we can relate to Sabine’s frustration: we’ve watched Antoine grow up (or at least older) over the course of the previous four films only to disintegrate into some truly impressive self-sabotage. We’re waiting for him to stop running.

Love on the Run is clearly fashioned as a final chapter, including as it does the return of most of the women who have mattered in Antoine’s life. In addition to Christine, we run into Antoine’s early girlfriend Colette (who snubs him so decisively in Antoine and Colette) and there is even a visit to the cemetery, where it is at last suggested that Antoine has made peace with his mother, whose treatment of him in The 400 Blows has echoed throughout the subsequent films despite her physical absence. Indeed, while the other Doinel films are subtly haunted by the past, Love on the Run openly confronts it. Antoine has finally published his autobiographical novel, Les Salades d’amour (the title of which winkingly lifts a line of dialogue from Day for Night), and the book inspires the people in Antoine’s life to retell and rethink the past.

Antoine’s meeting with his mother’s former lover, M. Lucien, followed by a visit to her grave at Père Lachaise, feels appropriate to the film. It’s an admirable attempt to chase away the ghosts that have dogged Antoine, one made more interesting by M. Lucien’s assertion that Antoine’s mother was misunderstood, an “anarchist” whose discontent as a mother reflected her discontent with society at large. But it is another woman from the past, Marie-France Pisier’s Colette, who emerges as one of the film’s most important and interesting characters. Now a lawyer, she runs into Antoine again during his divorce proceedings and hastens to pick up his novel. There wasn’t much to Colette in Antoine and Colette, and she was relegated to a brief cameo amid the myriad romantic complications of Stolen Kisses, but here she is something of a revelation: a woman of outward success and inward pain who chooses to help the typically hapless Antoine toward his happy ending. A scene regarding the loss of Colette’s child is one of the only newly-filmed flashback scenes in the film, and one of the most moving memories in a film that’s rife with them.

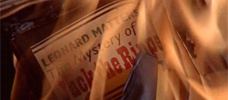

Those memories often offer Truffaut fans a sense of déjà vu. Released on the cusp of the home video era, Love on the Run contains roughly eighteen minutes of footage from other movies — there is a repurposed snippet of Day for Night in addition to the generous helping of scenes from the previous Doinel films — something that feels increasingly curious with time. Truffaut included the clips in order to take advantage of the unique situation created by his longtime collaboration with Jean-Pierre Léaud: Truffaut had most of Antoine Doinel’s life on film. The clips occasionally feel redundant in our own YouTube age — we take it for granted that we have all five Doinel films more or less at our fingertips — but sometimes they give the film added emotional heft. When Colette dips into Antoine’s novel for the first time, we see what she sees: a wince-inducing recollection of corporal punishment from the author’s school days. Truffaut also heightens the effect of Love on the Run’s ecstatic final scene by interspersing it with clips of Antoine’s happy, heady carnival ride from The 400 Blows. At best, the clips offer the film a fitting sense of circularity.

Truffaut’s challenge with this film was surely to create that sense of a circular journey without leaving us feeling that he, and Antoine, have simply been running in place. Léaud’s Antoine, noticeably older and maybe just a bit weary, might have left us permanently frustrated with his flightiness by now. “He’s always falling apart. He needs a wife, a mistress, a little sister, a nanny, and a nurse,” says another of Antoine’s ex-lovers, Liliane, echoing a complaint that Christine makes in Bed and Board. But he can still charm us, never more so then when, late in the film, he recounts the fantastic, outrageously romantic tale of how he first came to meet Sabine. In an interview quoted in the illuminating chronicle Truffaut by Truffaut, the director explains that after all of the melancholy and memory of the Doinel films, and Love on the Run in particular, he wanted to leave his most famous character with an ending that was “deliberately, brazenly, or if you wish, desperately HAPPY!” He delivers it: the last few moments of the film, buoyed by Alain Souchon’s wonderful title song, genuinely soar with joyous emotions. The final freeze-frame of The 400 Blows crystallizes Antoine’s isolation, but the breathless, jittery camerawork that signals the close of Love on the Run is seemingly unable to contain his elation.

All of this happiness comes with a caveat: as Sabine, French actress and TV presenter Dorothée is sweet but tough, and as much as she loves Antoine, she espouses little tolerance for his indecisive, infuriating approach to relationships. “…We can’t be certain it will last,” she says to Antoine. “But we can pretend it will.” “Right!” Antoine agrees. “Let’s pretend and see what happens.” It’s a perfect closing sentiment for the Doinel cycle, a series of films that have, from the start, acknowledged the uncertainty of life and the fragility of love — but celebrated the beauty of both, all the same.

More Love on the Run: The Films of François Truffaut

-

Les Mistons

1957 -

Une histoire d’eau

1958 -

The 400 Blows

1959 -

Shoot the Piano Player

1960 -

Jules and Jim

1962 -

Antoine and Colette

1962 -

The Soft Skin

1964 -

Fahrenheit 451

1966 -

The Bride Wore Black

1968 -

Stolen Kisses

1968 -

Mississippi Mermaid

1969 -

The Wild Child

1970 -

Bed and Board

1970 -

Two English Girls

1971 -

Such A Gorgeous Kid Like Me

1972 -

Day for Night

1973 -

The Story of Adele H.

1975 -

Small Change

1976 -

The Man Who Loved Women

1977 -

The Green Room

1978 -

Love on the Run

1979 -

The Last Metro

1980 -

The Woman Next Door

1981 -

Confidentially Yours!

1983

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.