Reviews

L’homme qui aimait les femmes

François Truffaut

France, 1977

Credits

Review by Adam Balz

Posted on 19 April 2010

Source MGM/UA DVD

By recollecting the pleasures I have had formerly, I renew them, I enjoy them a second time, while I laugh at the remembrance of troubles now past, and which I no longer feel.”

—Giacomo Casanova

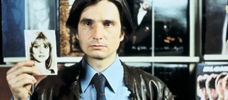

There’s a moment late in François Truffaut’s The Man Who Loved Women when three editors sit around the desk of a Paris publisher discussing The Skirt Chaser, an unsolicited memoir that has arrived from Bertrand Morane, an unknown writer living in Montpellier. The publisher and two of the editors are older men, their faces painted with perpetual indifference towards the manuscripts around them. The third editor is a young, vibrant woman named Genevieve who also happens to be the book’s lone defender, praising the writer’s near child-like inability to commit to any long-lasting relationship while, as the title implies, jumping with desperate passion from woman to woman.

“For me,” one of the male editors insists, “the best part of the book is when Bertrand Morane talks about his childhood and his relationship with his mother.” The other male editor seems to agree, adding, “It’s filled with contradictions. You don’t know what to think of him. Is he sick … a maniac … a pathological case … a disillusioned romantic?” But Genevieve comes to Morane’s defense with confidence, insisting, “He’s just a man!” Yes, she admits, the book has its contradictions, but adds that they are the “contradictions of life.” The two male editors are beside themselves. In this instance, however, they are correct: Bertrand Morane, the author of the manuscript, is an otherwise uninteresting man. By day, he is an engineer who tests the durability of ship and plane designs. But as his shift ends, one of his co-workers notes that Morane is never seen in the company of men after work, searching instead for the open arms (and welcoming beds) of female companions, all of whom he scouts as he walks the streets of Montpellier.

And yet, throughout the preceding ninety minutes of film, the array of Morane’s conquests - so extensive that Morane’s memory is no longer triggered by the drawer of photographs in his apartment, thus inspiring him to write his book - reveals itself to be little more than a lonely man�s theatre. Morane is a tired man desperate for the very companionship at night that he shuns the very next morning, or even immediately after the rendezvous is consummated. It is the kind of close, personal companionship that was robbed of him as a young man; as we see in the occasional black-and-white flashback, Morane is the son of a woman who was proud of herself yet seemingly ashamed of her lone child. Morane, a gawky adolescent in love with books, was often instructed to sit in a chair while his mother paraded half-naked in front of him—her attempt, he says, to prove to herself that he did not exist. She also kept photographs of her various male suitors, a habit that Morane himself admits to continuing, ashamedly, in his own life with his many female conquests.

These flashbacks, contrasted early in the film with Morane’s present isolation, act like Freudian daydreams. His roaming eye acting as a sort of guide dog, Morane follows women based on their bodies, seduces them with his effortless and unassuming charm, and takes them back to his apartment. The flashbacks are intercut among these escapades, blatantly suggesting that Morane’s desire for lovers is more of a desire for his mother—an Oedipal desire, perhaps, but more likely a need to be loved by women who remind him of his colorless and unhappy past. He is mired in those long-lost years, and even as he writes about his obvious misery, he seems dependent on them.

Strangely, by the film’s midway point, these flashbacks virtually disappear, and with little justification on the part of the director. They vanish as we’re plunged into the lengthy story of Delphine, an imbalanced lover who kills her husband to be with Morane. She is also the film’s most interesting character, and the few scenes with her are engrossing like none before. Suddenly there is conflict beyond Morane’s own questioning mind and his pathetic Freudian self-loathing. Naturally, though, Delphine is but a lengthy ripple in the film, destined to inevitably hit the shore and disperse, reappearing only once near the end after being released from prison and arriving at Morane’s apartment with a bottle of celebratory champagne. What follows that encounter is, sadly, a gratuitous and distractingly unrealistic moment beside the fireplace with Bertrand, Delphine, and a second woman.

Later, Genevieve refutes the comments of one of the male editors: “You say, ‘It’s difficult to see what he’s trying to prove.’ He doesn’t want to prove anything. He simply relates without discriminating between details that mean something and those that simply show the absurdity of life.” She calls the manuscripts instinctive and sincere, and it’s her passion for the otherwise doomed book that pushes her boss to publish it, and without edits. Still, you can’t help but feel that the film’s writers, Truffaut among them, added this scene intentionally to undermine any criticisms that The Man Who Loved Women, much like Morane’s book - the title of which, it should be noted, is eventually changed to the very same at Genevieve’s insistence - has no real point. Bertrand Morane is a round character, yes, but in the pantheon of interesting cinematic presences, he ranks near the bottom. Perhaps it’s my distance from Truffaut’s style, his era, or the country he called home, but ninety minutes of sad skirt-chasing, typing, and engineering, followed by a further half-hour of skirt-chasing mixed with the delicate world of book publishing, seems to have nary a point to make. And if it did - which I’m sure, deep down, it does - the screenwriters shouldn’t be forced to preemptively tell us this themselves.

More Love on the Run: The Films of François Truffaut

-

Les Mistons

1957 -

Une histoire d’eau

1958 -

The 400 Blows

1959 -

Shoot the Piano Player

1960 -

Jules and Jim

1962 -

Antoine and Colette

1962 -

The Soft Skin

1964 -

Fahrenheit 451

1966 -

The Bride Wore Black

1968 -

Stolen Kisses

1968 -

Mississippi Mermaid

1969 -

The Wild Child

1970 -

Bed and Board

1970 -

Two English Girls

1971 -

Such A Gorgeous Kid Like Me

1972 -

Day for Night

1973 -

The Story of Adele H.

1975 -

Small Change

1976 -

The Man Who Loved Women

1977 -

The Green Room

1978 -

Love on the Run

1979 -

The Last Metro

1980 -

The Woman Next Door

1981 -

Confidentially Yours!

1983

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.