Reviews

Les deux Anglaises et le continent

François Truffaut

France, 1971

Credits

Review by Jenny Jediny

Posted on 13 April 2010

Source Criterion/Janus Film VHS

An inversion of Truffaut’s more famous ménage a trois, Two English Girls replaces Jules and Jim with Anne and Muriel. Anne, brunette, athletic, impetuous and artistic, worships her sister Muriel, a frail redhead who suffers bouts of sporadic blindness and prefers to shut herself away in her bedroom. These are the women who enter a young Frenchman’s life and remain intertwined for decades; Truffaut’s second adaptation from a Henri-Pierre Roché novel, Les deux Anglaises et le Continent, Two English Girls resembles its predecessor Jules and Jim, but observes its love affair with older, far more weary eyes.

This period of Truffaut’s life was not an easy one, as the director was still affected by his mother’s death, despite their estranged relationship. There are also hints that he remained haunted by both the death of Françoise Dorléac and by her sister Catherine Deneuve’s subsequent termination of their relationship. Truffaut had deeply loved both sisters, as does the protagonist of Two English Girls’ Claude (portrayed by Truffaut’s alter ego, Jean-Pierre Léaud). In this difficult time, he found solace in Roché’s novel — so much so that he chose to showcase the novel “during the credits, [as] one is shown the pages of Roché’s book annotated by Truffaut, his deletions, his hesitations, and the words he circled in ink.”1

Like Jules and Jim, the early scenes of Two English Girls are full of youthful ardor, as Claude spends a summer with the sisters (and their watchful mother) at their home in the Welsh countryside. It is the late Victorian era, and England’s restrained, Puritan culture strongly appeals to young Claude, if only for its vast dissimilarity to his somewhat Bohemian childhood. Just as the German and French friendship between Jules and Jim prefaced World War I, the allusions to nineteenth-century Franco-English relations are evident here. The sisters affectionately refer to Claude as “the Continent,” citing the attraction of French culture for the siblings, while Anne and Muriel represent two halves of England’s splitting personality. Anne’s embrace of life is far more indicative of the forthcoming Edwardian era, while Muriel’s buttoned-up reserve and frequent ailments are quintessentially Victorian. While Claude will come to love both sisters, Muriel is the initial object of his desire, a passion reflected not only in the film’s embrace of nature — the sunswept moors and whitewashed cliffs are exquisitely shot by Néstor Almendros — but also in its highly Romantic tone.

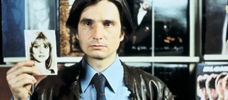

As Claude, Léaud is characteristically charming; wide-eyed and playful, he exudes a dedication to both Anne and Muriel despite impending affairs with other women, which mainly seem like a rehearsal for true love. It’s a colder portrayal than Léaud’s Antoine Doinel, but more nuanced, as both Anne and Muriel, respectively portrayed by Kika Markham and Stacey Tendeter, project their desires — in some sense, their entire personalities — onto Claude. Truffaut keeps both Anne and Muriel just out of reach of our full comprehension, rendering their characters alluring ciphers rather than actual women, as we learn of their feelings and fears through their speeches, letters, and late night talks with Claude (who is also their teacher, as they are aiming to improve their French).

Truffaut looked to the Brontë sisters for inspiration in developing the characters of Anne and Muriel, and indeed the love between the girls and Claude is a slow burn worthy of Catherine and Heathcliff. Claude and Muriel are inevitably separated by their mothers, who believe their plans for marriage are rushed and unrealistic. The remainder of the film deals with that separation, and the inability of time to break either their own bond or their mutual ties to Anne. While the emotional connections are made clear through love letters and voice-over supplied by Truffaut himself, lending insight into Claude’s thoughts, Two English Girls is also keenly interested in the physical aspects of love, meditating not merely on the engulfment of long-held passion, but on the implication of mortality involved in lovemaking as well. While Anne’s carnal experience with Claude is quintessentially romantic (taking place in a Swedish lake chateau no less), Muriel’s is both emotionally and physically raw, so much so that Truffaut lets the camera linger on the virginal blood staining the sheets.

While we are allowed glimpses into each sister’s psyche, it is Claude who remains the most accessible character, and who we see grow from a childish young man hanging from monkey bars to one who is suddenly middle-aged, as in a Proustian moment toward the close of the film when he catches his reflection in a car window and is quietly astonished that he looks so old. Two English Girls captures the pain of love, but also the fleeting passage of time; while Claude has already mourned lost love, there is a sense that with age, he has finally begun to feel the inescapable anguish of the time he’ll never regain.

- Antoine de Baecque & Serge Toubiana, Truffaut: A Biography, 284.↩

More Love on the Run: The Films of François Truffaut

-

Les Mistons

1957 -

Une histoire d’eau

1958 -

The 400 Blows

1959 -

Shoot the Piano Player

1960 -

Jules and Jim

1962 -

Antoine and Colette

1962 -

The Soft Skin

1964 -

Fahrenheit 451

1966 -

The Bride Wore Black

1968 -

Stolen Kisses

1968 -

Mississippi Mermaid

1969 -

The Wild Child

1970 -

Bed and Board

1970 -

Two English Girls

1971 -

Such A Gorgeous Kid Like Me

1972 -

Day for Night

1973 -

The Story of Adele H.

1975 -

Small Change

1976 -

The Man Who Loved Women

1977 -

The Green Room

1978 -

Love on the Run

1979 -

The Last Metro

1980 -

The Woman Next Door

1981 -

Confidentially Yours!

1983

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.