Reviews

John Fawcett

Canada, 2000

Credits

Review by Glenn Heath Jr.

Posted on 22 October 2011

Source First Look Pictures DVD

Categories 31 Days of Horror VIII

Werewolves and horny pubescent teenagers are strikingly similar beasts. Their extreme appetites are defined by powerful physical transformation, specifically human bodies that suddenly morph into foreign and frightening molds. Scent and taste become elevated and instinctual urges overwhelm all sense of sensible control. The afflicted quickly careen into an exaggerated state of consciousness, a heightened headspace where ripping someone’s clothes off or tearing apart their flesh are equally synonymous. This can be a gloriously sexy and terribly disturbing place all at once. Why no horror filmmaker thought of combining the two before John Fawcett’s Ginger Snaps is baffling, and kind of amazing. Oh, and Teen Wolf doesn’t count.

A place full of dead ends.

Ginger Snaps begins cornered, with rows of houses unflinchingly stacked on top of each other thanks to a stiflingly effective telephoto lens. Electric wires crisscross the frame, further clogging the already cramped suburban façade. Baily Downs isn’t much to look at even by one’s lowest standards. It’s just another classic conformist hell where life goes on without much fuss despite the fact that multiple dogs are being ripped apart on a nightly basis. In the opening sequence, one devoured carcass is found by a quiet young boy playing in the sandbox, his hand reaching below the frame and picking up a severed limb all to his mother’s horror. The boy even smears blood on his face as if it were paint, the beginning a jet-black comedic streak that runs down Ginger Snap’s lycanthrope spine.

The Fitzgerald sisters, who form the central coupling and core thematic dichotomy in Ginger Snaps, are notorious throughout Baily Downs for being dangerous loners and potentially future sadists. Bridget, seemingly 13-years old in theory only, has naturally drowsy and soulless eyes that are perpetually aimed at the floor as she lurches forward through any given space. Her sister, the more conniving and ambitious 16-year old, Ginger, is obsessed with fulfilling a life long goal of suicide (the pair have even planned on dying together in dramatic fashion). Their clueless parents ignore the severity of these whacked out plans, even though the gothic pair has been staging and photographing unique death scenes for years. Ignorance truly is bliss in Ginger Snaps.

See, you’d let idiots get away with fucking you up. That’s why they big Buddha made me. To stop them.

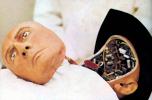

Ginger’s words may seem protective in nature, but her actions are always self-serving, even when pressed by glib attackers. She wants Bridget to follow her every move, to justify sisterhood by becoming a nasty, subversive clone. That Ginger gets her first period, an impending natural cycle she has been trying to will off for years, and is bitten by a blood-thirsty werewolf in the same week, becomes an essential thematic connection in Ginger Snaps. Almost immediately, Ginger’s body and mind begin to change, alienating Bridget into a kind of moral and ideological limbo. Once a follower of her sister’s bullying tactics, Bridget is forced into responsible adulthood so she can save her Ginger from becoming a whole different kind of monster. To complicate matters worse, as Ginger’s body starts sprouting thick hair and grows a knobby tale she immediately turns promiscuous and aggressive, making herself into an even bigger social pariah than before. It seems whether in the form of a teenage vixen obsessed with suicide or a snarling werewolf hell bent on disemboweling the nearest guy meat, Ginger is a force of nature.

Something wrong? Like more than you just being a female?

Ah, but unlike most werewolf films, Ginger Snaps is almost entirely about the process of becoming, the arc of turning from one uncomfortable life form into another. Teenage self-awareness becomes a parallel experience for animalistic transformation, both equally elemental and evocative shifts in perspective. Ginger’s lust for sex and blood go hand in hand, a way to experiment with her new found sense of power by destroying the boundaries of social gender roles. Fawcett’s characters fully understand the entrenched hierarchies they face on a daily basis, especially at school when they are objectified by the jocks and put down by the reigning popular blondes. Ginger’s violent interludes, including a devastating back seat ride with sex-crazed football star, are potent ways of defying the expectations placed on her by others.

No one ever thinks chicks do shit like this. A girl can only be a slut, a bitch, a tease or the virgin next door. We’ll just coast on the way the world works.

And Ginger is right. Her evolution occurs in plain sight of fellow classmates, teachers and parents, and no one bats an eye. She even goes to the school nurse but is denied any real attention or respect. So Ginger’s natural reaction is to embrace her new shell and begin to explore the possibilities of terror she can inflict on those most deserving. It’s especially great that the film’s brutal extended climax begins in the very hallways the sister’s have walked for years, then shifts to their childhood home, another symbol of individual repression. Doors are torn apart, windows shattered, and blood is spewed in fitting arterial spray across every surface. Ginger is no longer a teenager, but a bulky slobbering wolf devoted to one thing: destroying everything she sees, including her sister. In this way, Ginger Snaps is a fitting allegory for sibling rivalry, a melodrama animated to the state of horrific delirium.

Time is the most heinous enemy to both lead characters in Ginger Snaps, so it makes perfect sense neither Bridget nor Ginger can stop any of the temporally sensitive dramatic moments from coming true. In the end, that’s what’s most horrific about Ginger Snaps, a seemingly straightforward horror film that utilizes the real life pressures of adolescence for maximum genre effect. There’s a desperate futility in trying to prolong the inevitable, and this doesn’t just relate to puberty, or becoming a werewolf, but impending adulthood, old age and finally death. Fawcett shows that all of the effective jump scares, kinetic chase sequences, and off-screen audible chills are simply more cinematic ways of resisting what cannot be resisted, taming what cannot be tamed. We’re all just animals biding time, so lets hunt.

More 31 Days of Horror VIII

-

Westworld

1973 -

Child’s Play

1988 -

Jacob’s Ladder

1990 -

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

1971 -

El Vampiro

1957 -

28 Weeks Later

2007 -

Piranha II: The Spawning

1981 -

The Others

2001 -

Quatermass and the Pit

1967 -

I Know Who Killed Me

2007 -

Bride of Re-Animator

1990 -

Alucarda

1978 -

Kakashi

2001 -

Seizure

1974 -

Night of the Living Dead

1968 -

Night of the Living Dead

1990 -

The Bat Whispers

1930 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Tintorera

1977 -

Paradise Lost

1996 -

The Cars that Ate Paris

1974 -

Ginger Snaps

2000 -

J.D.’s Revenge

1976 -

The Wicker Man

2006 -

Black Water

2007 -

Don’t Panic

1988 -

The Driller Killer

1979 -

Targets

1968 -

Mahal

1949 -

Event Horizon

1997

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.