Reviews

Chris Sivertson

USA, 2007

Credits

Review by Megan Weireter

Posted on 10 October 2011

Source Sony Pictures DVD

Categories 31 Days of Horror VIII

As an optimist, I believe that lost somewhere in the hot mess of I Know Who Killed Me is the germ of an idea that is not completely terrible. To borrow a scene from the movie: Imagine a girl who’s been gruesomely tortured, then enclosed in a comically elaborate blue stained-glass coffin and buried alive. The not-terrible idea at the heart of this film is like that girl: damaged, delicate, covered in a glassy layer of pretentious quasi-artistry and another layer of filth.

I’m sorry—that’s a ridiculous, overwrought metaphor. If you enjoy the ridiculous and overwrought, though, you might want to check out I Know Who Killed Me. As a Lifetime movie or a long story arc on General Hospital, it could have been fantastic. But as a gritty horror film and vehicle for Lindsay Lohan to prove her acting chops, it fails.

The premise here is that Aubrey Fleming, an overachieving teenager born into a life of privilege, is abducted, only to reappear days later missing two limbs and all memory of who she is. Instead, she insists that she is actually a troubled young stripper named Dakota Moss. She relates stories of an entirely different past that flummox Aubrey’s well-meaning friends and family.

This could have been a decent start to a horror film. Real tension around the psychological vulnerabilities and unstable identities of teenagers could have developed as the mystery unraveled. Aubrey is a fiction writer, and the excerpts we hear of her short story are all about the adolescent condition. “She always felt like half a person, half a person with half a soul… She always woke to the same feelings of loneliness and loss.” Clunky though this may be, there’s at least a thread of relatability. But rather than allowing viewers to connect to that feeling, the film explores what it means to be “half a person” with dunderheaded literalism. That means amputations, identical twins, ponderous monologues about love/hate and peace/war and the dual nature of everything, and a dichotomy of color symbolism so over the top it would make F. Scott Fitzgerald blush.

In chronicling what went horribly, horribly wrong in this film, we may as well start with color, because it’s obvious that we’re not supposed to miss it. Aubrey, the good girl, is always blue. Blue filters, blue clothing, blue roses, blue uniforms for the high school football teams—right down to the blue gag the villain eventually uses on her. Dakota, the bad girl, is always red: red filters, red stripper outfits, red lipstick. The one good thing about this visual shorthand is that it’s helpful in telling the difference between the two: Lohan rises to her dual acting challenge by playing Aubrey with a permanent scowl of overserious intensity, and Dakota with a permanent scowl of world-weary hostility. When the scowls are too difficult to tell apart, you can always check the color to see where you are. It’s not just the girls themselves, though. Every scene is saturated with blues or reds so thick that you almost have to gasp for air. But it’s the lack of subtlety of the blue and red, even more than the lighting, that becomes truly oppressive. By the time a psychiatrist starts taking notes on both girls in different colored pens - blue for Aubrey, red for Dakota - you just want to shout at the screen that WE GET IT ALREADY.

And that’s another problem with this film: director Chris Sivertson is so in love with his own apparent cleverness that he can’t help himself from heaping on visual tricks, even when doing so renders everything nonsensical. There’s not a single shot in this movie that doesn’t try to mean something. There are the colors, of course. There are also owls. What the owls mean isn’t clear, but they sure do pop up everywhere, from the high school mascot to graffiti at the bus stop to a cookie jar in the Fleming kitchen. Almost every dissolve is supposed to be significant, too, but most of them just seem silly: a scene of Dakota trying out her new artificial leg dissolves into a close-up of a police siren (red and blue again!), while elsewhere a close-up of branches going into a wood chipper dissolves into the American flag. You can bet these are supposed to mean something, but who can say what exactly? And then there’s the slow motion - without all the gratuitous slow motion scenes, this movie could probably have been about a third as long - and the high melodrama of the score, which becomes hilariously literal in its use of crazed piano music for the final chase scenes between Dakota and a crazed piano teacher. Not only is this all a bit exhausting, but there’s nothing going on here that actually sustains the arc of suspense that a good thriller would require. Instead, it manages to be simultaneously confusing and insulting to our intelligence.

I’m not opposed to this kind of pretentiousness, especially when it’s in service of a screenplay as profoundly silly as I Know Who Killed Me—normally, that would be a recipe for the best kind of camp. But there’s something about the self-congratulation and literalism of all of this that’s cloying rather than fun. Though Sivertson seems to be trying to imitate the work of the great Italian horror directors, he lays it all on with too heavy a hand and with too much strained significance. Ultimately, there’s nothing to the movie except the answer to the central mystery of Aubrey/Dakota’s identity—and, secondarily, the identity of the killer. The showiness here don’t really add any depth. It functions as cinematic icing, and like too much icing, it eventually starts to make you kind of sick. Which is a real shame, because all the other ingredients are in place here for perfect camp: wooden exposition-loaded dialogue, an ripped-from-the-headlines look at the seedy underworld of crack dens, a walking stereotype of a strip-club madame, and inspiring scenery chewing from Julia Ormond, who plays Aubrey’s mother, as well as the entire bumbling police force. The whole thing stinks of missed opportunity.

When I say that there’s nothing to the movie except the answers to the mysteries (which are pretty obvious anyway), that’s not entirely true. The other reason to watch is old-fashioned voyeurism, which this delivers in spades. I find the most successful scenes to be the smuttiest of them all: the scenes in the strip club. Dakota writhes in unceasing slow motion, bathed in red light, modestly keeping her bra on while performing actions with a patron’s cigarette that will not so much titillate you as make you want to throw up. (Much as it pains me to admit it, I Know Who Killed Me might even best Showgirls for the dubious honor of Most Disgusting Thing Done to a Stripper Pole in Cinema.) This scene is all about voyeurism for its own sake, and it’s refreshingly unpretentious and honest about that. In a movie with such a suffocating sense of self-importance, this scene is like a bizarre breath of fresh air before we move on to the inevitable conclusion and the grisly dispensation of justice. None of what follows is as surprising or shocking as what Dakota does with that cigarette, so let’s leave it the film there, and revel in the unrealized camp potential of that moment.

More 31 Days of Horror VIII

-

Westworld

1973 -

Child’s Play

1988 -

Jacob’s Ladder

1990 -

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

1971 -

El Vampiro

1957 -

28 Weeks Later

2007 -

Piranha II: The Spawning

1981 -

The Others

2001 -

Quatermass and the Pit

1967 -

I Know Who Killed Me

2007 -

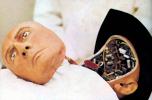

Bride of Re-Animator

1990 -

Alucarda

1978 -

Kakashi

2001 -

Seizure

1974 -

Night of the Living Dead

1968 -

Night of the Living Dead

1990 -

The Bat Whispers

1930 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Tintorera

1977 -

Paradise Lost

1996 -

The Cars that Ate Paris

1974 -

Ginger Snaps

2000 -

J.D.’s Revenge

1976 -

The Wicker Man

2006 -

Black Water

2007 -

Don’t Panic

1988 -

The Driller Killer

1979 -

Targets

1968 -

Mahal

1949 -

Event Horizon

1997

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.