Reviews

Adrian Lyne

USA, 1990

Credits

Review by Michael Nordine

Posted on 03 October 2011

Source Lion’s Gate DVD

Categories 31 Days of Horror VIII

A little less than two decades ago, my stepdad went on a skiing trip in rural Vermont. One extremely windy night after a long day out, he found himself unexpectedly alone in the rented house he and his friends were sharing for the weekend. With nothing but an apple pie from a local diner and a VHS copy of Jacob’s Ladder rented on a whim, he decided to spend the night in. Through some combination of the stormy weather, being by himself, and the genuine fear evoked by the film, he found himself quite shaken. “I’m not one to get spooked by shit like this,” he told me recently as I prepared to watch it, “but when you calibrate your expectations for something and it ends up being completely different, it sticks with you.” Between my stepdad’s recounting of his one and only viewing of the film and its trailer, which I watched around this time last fall as I contemplated taking on the film for last year’s edition of 31 Days of Horror (I chickened out, obviously), Jacob’s Ladder was until very recently one of a small handful of movies I avoided watching for the simple reason that I was too scared to do so. As the film itself explores, there are few things more frightening than what we conjure ourselves, and my murky conception of this story - psychological, slow-moving, and genuinely creepy - was enough to keep me away until just this week.

My stepdad’s experience is of the sort I wish were more common today. It’s increasingly rare to be truly alone these days, what with smart phones and WiFi being nearly ubiquitous, but certain situations demand it: namely, watching a movie like Jacob’s Ladder. I, too, watched it on my lonesome, but the amount of people within 100 yards of me at the time surely numbers in the hundreds. Had I stepped out my front door or opened a window, I would have been greeted by a chorus of ice cream trucks, obnoxiously loud children, and traffic. It turned out not to matter. Jacob’s Ladder is engrossing enough to make you feel like part of its claustrophobic world, despite how badly you want to escape it, and any reminders of the outside world come as welcome distractions. This in spite of the fact that overt moments of horror are relatively infrequent: Adrian Lyne’s movie cultivates fear largely via the viewer’s ability to fill in the blanks with his or her own thoughts and projections. As tends to be the case, the result is an occasional urge to avert your eyes from the screen, afraid of what will or won’t happen next.

A cold viewing would have you believe, at least for the first several minutes, that you’d stumbled upon a war movie—which, in a sense, you have. Jacob’s Ladder uses as its narrative launchpad a neurological experiment conducted on U.S. soldiers in Vietnam gone awry. For Jacob Singer and the rest of his company, none of whom have a clear recollection of the event, the residual effects seep well into their postwar lives in a twofold manner. They’re haunted not only by what they endured but also by the hellish form their memories have taken on. Jacob’s Ladder has a decidedly infernal underbelly to it, one announced early on in a New York City subway ad reading simply HELL (placed, carefully enough, next to a tourism poster for the city) and compounded by Jake perusing through an illustrated copy of Dante’s Inferno and one of his fellow soldiers proclaiming, quite bluntly, “I’m going to hell.”

Jake’s personal hell has as much to do with the fact that he’s going through a divorce and still recovering from the death of his son (played, it seems worth mentioning, by a pre-Home Alone Macaulay Culkin) as with his haunting visions. Always in the back of his mind, these many troubles lend everything from pillow talk with his girlfriend to an already-strange house party an almost tangible feeling of anxiety. Nary a moment goes by that isn’t somehow replete with this dread, whether it’s Jake getting told by a palm-reader that his lifeline indicates he’s already dead or the contorted faces of men and women in the backseat of cars, on the streets, in his mind. Externalizing someone’s dread in such a manner isn’t particularly now, but here the line between dream, nightmare, and reality is blurred in such a way that the viewer is never able to relax. Understanding one scene as “real” and another as “fake” would make latching onto and understanding them easier, but we’re never given that luxury. Like Jake himself, we’re forced to wander through both the dingy, strangely empty streets of New York and the darkest recesses of his mind, rarely sure which is which. It’s an immersive experience made up of equal parts horror and sorrow.

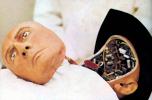

And then there are the demons. Wholly grotesque and perhaps more unsettling than they should be, they’re nightmares made flesh—quite literally the materialization of Jake’s most repressed, permeating fears. They start out as strange growths on the back of people’s heads or on their hands of which we only get a glimpse and gradually evolve into tails, horns, and claws growing out of bodies. As a barometer of Jake’s mental state, their increasing gore says much. A long series of these mini-crises comprise the first half of the film, and they’re broken up by recurring Vietnam flashbacks and dreams-within-dreams, each of which reveals another piece of Jake’s psychological puzzle. As revealed partway through the film, he’s joined in his visions by the other soldiers of his company, but rather than bring them closer together, they eventually distance them to the point where Jake hardly knows them any longer. Even the darkest war films tend to highlight the fraternal bond between the soldiers who experience it together, but external forces in the aftermath of these men’s shared trauma have torn them apart from one another. Jake’s hell is composed largely of isolation from everyone around him who might be able to help him better understand his visions.

Were all this part of a straightforward horror film, it would be par for the course and perhaps even banal. But Jacob’s Ladder only belongs to the horror genre insofar as it understands its conventions well enough to simultaneously borrow from and transcend them. In the process, it becomes something else altogether. We expect to see grotesqueries and hellish visions of the world in a Friday the 13th movie but, when transplanted into a story about a man haunted by both his wartime experience and the death of his young son, it’s mostly just sad. As much as anything this movie is about the power of perception, of understanding our own demons not as the manifestation of our deepest fears but as something to put behind us. Expressed via a quotation relating to the duality between angels and demons delivered by Jake’s strangely angelic chiropractor, this comes as a revelatory burst of wisdom for our protagonist. In biblical terms, Jacob’s Ladder is a means of reaching heaven. That may be true here as well, but one must first descend into hell to understand the difference.

More 31 Days of Horror VIII

-

Westworld

1973 -

Child’s Play

1988 -

Jacob’s Ladder

1990 -

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

1971 -

El Vampiro

1957 -

28 Weeks Later

2007 -

Piranha II: The Spawning

1981 -

The Others

2001 -

Quatermass and the Pit

1967 -

I Know Who Killed Me

2007 -

Bride of Re-Animator

1990 -

Alucarda

1978 -

Kakashi

2001 -

Seizure

1974 -

Night of the Living Dead

1968 -

Night of the Living Dead

1990 -

The Bat Whispers

1930 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Tintorera

1977 -

Paradise Lost

1996 -

The Cars that Ate Paris

1974 -

Ginger Snaps

2000 -

J.D.’s Revenge

1976 -

The Wicker Man

2006 -

Black Water

2007 -

Don’t Panic

1988 -

The Driller Killer

1979 -

Targets

1968 -

Mahal

1949 -

Event Horizon

1997

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.