Reviews

Scarecrow

Norio Tsuruta

Japan, 2001

Credits

Review by Michael Nordine

Posted on 13 October 2011

Source torrent download

Categories 31 Days of Horror VIII

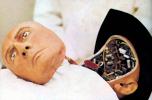

In terms of mythical and folkloric monsters - werewolves, vampires, mummies, and so on and so forth - the scarecrow is something of an outlier. It is, aside from the zombie, the only such creature to which I personally have ever been particularly drawn, and perhaps the most underused. Possessing neither the eroticized flair of the vampire nor the same thematic capacity of the zombie, the scarecrow has no contemporary Twilight equivalent or a directorial proponent such as Romero to bring it into the spotlight, and so it remains a peripheral figure even within the marginalized genre to which it belongs. Why not? Why no Brendan Fraser-led franchise devoted to the creature, or even an ill-advised attempt to revitalize and reboot its popularity (see: The Wolfman)? Likely it has to do with the scarecrow’s inscrutability: faceless and unmoving, it possesses only what qualities (frightful or otherwise) the viewer projects onto it—its central feature, in other words, is a complete lack of features. Lending itself more to subtlety than to melodrama, it is the monster world’s purest tabula rasa, and to date a woefully untapped resource.

While other creatures have reached such cultural ubiquity that their presence in film is generally accepted without question, scarecrows, largely by virtue of the fact that they exist in the real world in a rather mundane manner, need to have their onscreen appearances explained and qualified. Case in point: Kakashi. The film opens with a particularly long epigraph explaining their history as a specific form of scarecrow used not only to protect the fields from evil spirits but, just as importantly, attract benevolent ones. (A double-edged sword, their potential as a force of both good and evil is foregrounded throughout the film.) Not long thereafter, the car of our heroine - a young woman named Kaoru who’s looking for her lost brother - breaks down in an empty tunnel. Moments later she meets an old man whose manner of speech is as laconic as it is cryptic and, following his advice, she then travels down a country road on foot—only to find that, contrary to what she’s just been told, it forks. Kakashi is only sporadically frightful, not only because its attempts at producing fear are hackneyed but also because of the relative rarity of the attempt themselves. The film is driven more by mood than it is by fear, but even this tends to be more off-putting than engaging. So frequent are instances of maudlin piano chords and close-ups on Kaoru’s face (neither of which are helped by the low production values) that the film sometimes resembles a TV soap opera aiming for Twin Peaks but landing far short of the mark. It’s nevertheless worth discussing in some depth because the quiet moodiness with which it unfolds is not only compelling in its own right but also implicative of the film’s larger concerns: how we do - and just as often don’t - move on from tragedy and resume our daily lives.

Kaoru is admirably proactive throughout the film. After fruitless jaunts through the village in which she finds herself searching for answers by day (excursions which serve mostly as an opportunity to trot out the villagers, who are preparing for an annual kakashi festival, in all their creepy glory), she’s visited nightly by a kakashi whose intentions are unknown to her. We are at first made to believe that these are merely dreams, but the presence of straw clenched within Kaoru’s palm upon waking suggests otherwise. Her attempts to bridge the gap between what she sees and what she knows to be true are taxing, but she’s left with no choice. That the scarecrows littered throughout the village eventually come half-alive as trapped, hostile souls points toward a preoccupation with how we as humans transition from this world into the next and the inherent danger - and deep-seated, permeating fear - of doing so. Our time in these earthly bodies is grief; like Kaoru, we can only hope to stave off death for as long as possible and, when our time comes, hopefully go in peace. Kakashi aims to show what might happen should we not be so lucky. To become a kakashi is to keep fighting after the battle has already been lost, to flail about in a purgatorial space in the vain hope of grasping something that will bring you back. That Kaoru must fight with every fiber of her being to avoid becoming one (and, later, contentedly accept what’s transpired) is as close as the film comes to irony.

Thematically rich though they might be, slow-moving scarecrows do not make for especially imposing foes. Their ubiquity in the village is nevertheless a chilling enough statement on the inevitability of death. As someone who’s been launched into full-blown panic attacks by especially sudden, hard-hitting realizations of his own mortality - the shortness of breath, the feeling of stepping into a darkness from which there’s no stepping out - I can certainly appreciate this form of horror in the abstract, but in practice it leaves something to be desired. Like the creatures of its title, Kakashi is caught between two worlds, only in this case it’s an inability to resolve the tension between the conventions of different genres which, while far from mutually exclusive, receive a muddled expression here. Its most legitimately scary moments consist almost exclusively of close-ups of the scarecrows’ faces, the blankness of which is legitimately chilling. At one point in her search for her brother, Kaoru comes across a notebook written as through from beyond:

Kaoru Kaoru Kaoru Kaoru Kaoru Ka

Pages and pages of this - of her own name written perfectly at first and then more and more illegibly as each page is turned - are preceded by the simple declaration “I curse you.” Kakashi is a self-contained dreamscape of sorts, with moments such as this one punctuating an otherwise dull milieu made up of wandering and miscommunication. Even the too-easy manner in which it resolves itself is akin to waking from an unpleasant dream: a relief to be sure, but also a disappointment. The kind of strangeness on display here, when done right, is a highly effective means of building tension and fear, but too often we’re even more lost than Kaoru is. “Is this a dream or a fantasy,” she and several others ask throughout the film; it says much that the question asked is never whether what we’re experiencing is actually happening, but rather the extent to which it’s unreal.

More 31 Days of Horror VIII

-

Westworld

1973 -

Child’s Play

1988 -

Jacob’s Ladder

1990 -

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

1971 -

El Vampiro

1957 -

28 Weeks Later

2007 -

Piranha II: The Spawning

1981 -

The Others

2001 -

Quatermass and the Pit

1967 -

I Know Who Killed Me

2007 -

Bride of Re-Animator

1990 -

Alucarda

1978 -

Kakashi

2001 -

Seizure

1974 -

Night of the Living Dead

1968 -

Night of the Living Dead

1990 -

The Bat Whispers

1930 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Tintorera

1977 -

Paradise Lost

1996 -

The Cars that Ate Paris

1974 -

Ginger Snaps

2000 -

J.D.’s Revenge

1976 -

The Wicker Man

2006 -

Black Water

2007 -

Don’t Panic

1988 -

The Driller Killer

1979 -

Targets

1968 -

Mahal

1949 -

Event Horizon

1997

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.